One of Lubbock’s favorite sons, Buddy Holly, died 59 years ago Saturday in a plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa. Holly left an indelible mark on popular music and culture that lingers to this day. Those looking to remember him can find plenty of homages to the rock and roll icon in Lubbock including a giant, 750-pound pair of his signature glasses. But it took the staunchly conservative city about two decades to begin recognizing Holly’s worldwide musical influence.

In the early 1950s, Lubbock High student Betty Dotts was into music: classical piano. She sang with Buddy Holly in the school choir and knew he had grander ambitions. She was skeptical.

“When I heard him play, I thought, ‘oh, my goodness, that’s not very good music,’” Dotts says.

It’s hard to believe when you think of Buddy Holly now, but, early in his career, many in his hometown didn’t think much of his songwriting, vocal or guitar talents.

George Nelson, another Lubbock High choir member, felt differently. Today, he’s an attorney, but in his teen years, Nelson also enjoyed songwriting.

“Never had anywhere near the talent that Buddy had,” Nelson says. “He was just innately endowed with it.”

In 1953, Nelson and Holly faced off in a song contest. Nelson’s tune, “Someday You’ll Pay,” won.

“The only thing that I’ve got in my life that I can brag about musically. And he could play,” he says.

“He sang strictly country music back then, country-western music,” says Larry Byers, a former DJ in Lubbock. He heard Holly’s early performances live on local radio and at venues around the city.

“…until he saw Elvis Presley, and decided that maybe he ought to change his style a little bit,” Byers says.

At the same time Elvis and late night radio were inspiring Holly, rock-and-roll was scandalizing the nation. It got an especially cold reception in Lubbock. Preachers, including the one at the Baptist church that Holly’s family attended, abhorred the music. George Nelson remembers preachers regularly smashing vinyl records or using cars to crush them.

“The real ultra conservative people thought the young people were going to,” Nelson says.

Local teenagers who wanted to listen to rock-and-roll would circle their cars out in cotton fields, blast the radio and dance.

After high school, Holly threw himself into pursuing a music career. And well, you know the story. His success was cut short in 1959. Holly was just 22 when he was killed in a plane crash in Iowa, along with two other up and coming musicians, Ritchie Valens, and J. P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson.

Holly’s old classmate, Betty Dotts, says his hometown was slow to realize who they’d lost.

“Certainly he put Lubbock on the map, places all around the world,” Dotts says. “And Lubbock, it took ‘em a long time to finally step up and recognize, because that’s really outstanding what he did. That doesn’t happen every day.”

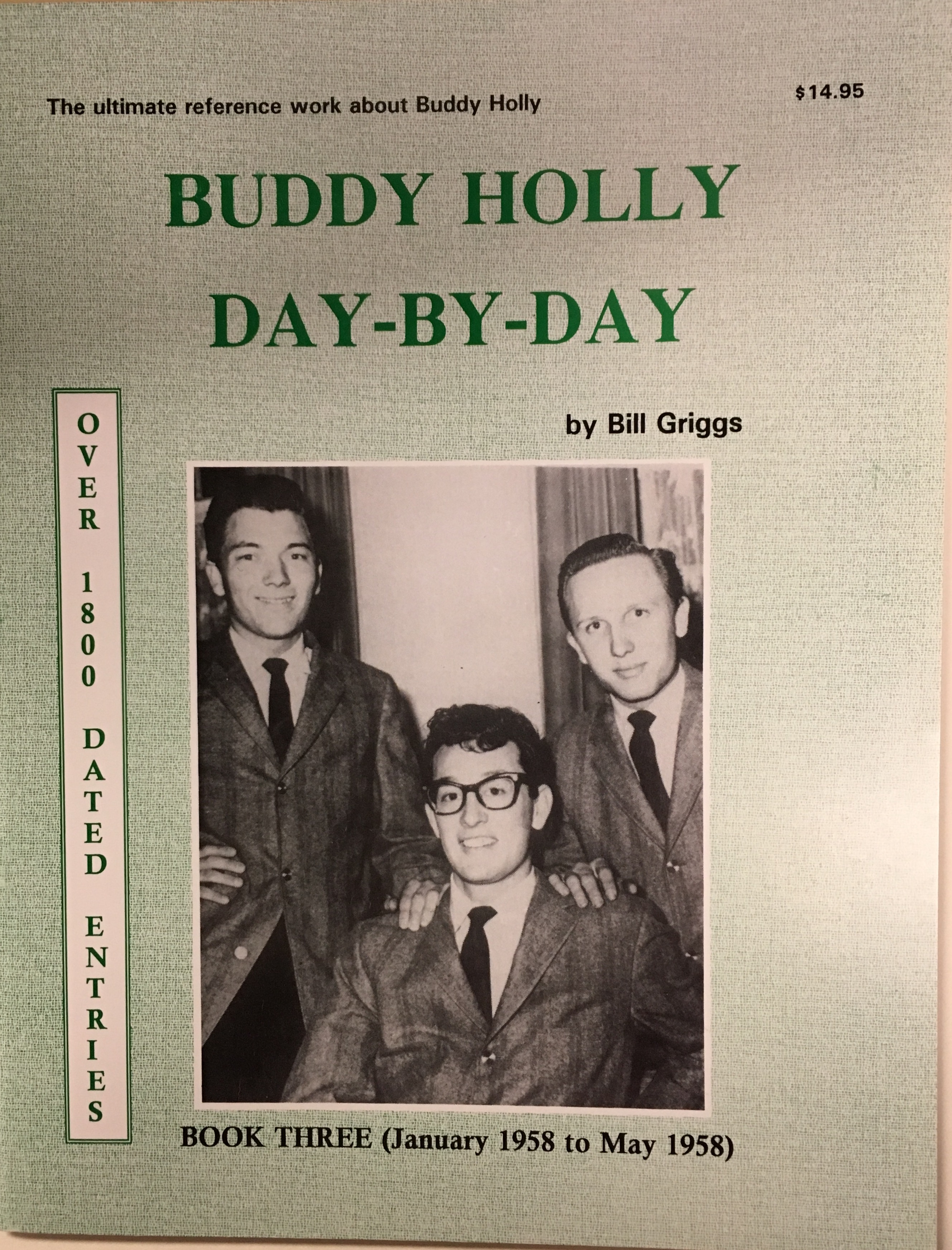

It would be almost 20 years later, when the 1978 movie “The Buddy Holly Story” was released, before the city gradually began to publicly spotlight Holly’s talents. These days, Holly has a street, a park with a bronze statue of him, a museum and a recreation area named after him. And the Crossroads of Music Archive at Texas Tech University houses the research of the late music historian Bill Griggs, inarguably the world’s foremost authority on Holly. Griggs assembled a thorough accounting of Buddy Holly’s life. Every day of it, in fact.

Curtis Peoples, an archivist, reads from “Buddy Holly: Day-by-Day.”

May 31, 1956, Thursday. The John Wayne movie titled The Searchers opened at the State Theater. Buddy and Jerry Allison went to see it. The movie cost them 65 cents each. During the movie, John Wayne would mutter, “That’ll be the day” each time he was disgruntled about something.

Buddy and Jerry decided to write a song later that evening. By now you know what the title was.

The archive’s collection includes five magazine-style volumes full of similar entries. Research like this, artifacts from Holly’s life, and stories from people who knew him will be getting a lot of attention this year. Lubbock’s preparing to mark the 60th anniversary of Buddy Holly’s passing, in 2019.

And even more is in the works. Last year, construction started on the Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Sciences, in Lubbock’s art district. It’s slated for completion by 2020. Not a bad legacy for a guy whose classmates didn’t think he’d amount to much musically.