Just off of Louisiana’s Highway 6, about 30 miles east of the Sabine River that separates the state from modern day Texas, you’ll find the remains of the long-lost first Spanish capital of Tejas – one you’ve probably never heard about. It was buried for hundreds of years, until one archeology student decided to dig it up.

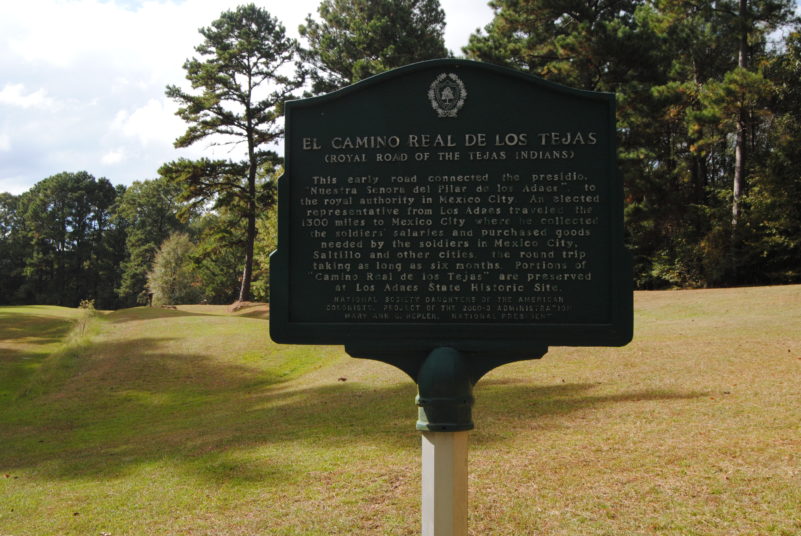

When Pete Gregory first visited this site in the ‘60s, there wasn’t much to see besides grass and pines. And a sign.

“Well I’m an archaeologist and if someone puts up a sign on the side of the road and says this is a a fort, I thought well, Maybe so,” Gregory says.

Back then, the now Dr. Gregory was working on his dissertation at Southern Methodist University. So, he decided to check it out.

“I could just walk up and down the road and look around around, so I started picking up pieces of Spanish pottery and French pottery and Indian pottery, and it looked more and more like, gosh, somebody’s right,” he says.

Starting in 1966, Gregory helmed a series of archaeological investigations that proved the site was Los Adaes, the little-known capital of Spanish provincial Texas.

The story of Los Adaes begins when the Spanish started claiming the so-called “new world” back in the 1500s.

Their empire reached from South America all the way up through modern-day Texas and along the Gulf coast, over to Florida. The Spanish didn’t do much to populate it in the present-day U.S. But they called dibs on it. And that was all well and good, until they got some new neighbors, says Michael Mumaugh, site manager at the Los Adaes State Historic Site.

“France comes in, in the mid-1600s up the Mississippi, they start claiming territory,” he says. “Neither side has population there. This is all native American territory, which is being carved up by European powers.”

These new occupants made the Spanish a bit nervous, so they started beefing up their presence on the remote northeastern frontier.

“Here in 1717, San Miguel Mission will be the furthest east of the Spanish missions in New Spain, set up mostly to keep tabs and show the French in Natchitoches that come no further, this is our land,” Mumaugh says.

A couple of years later, they built a fort to go along with that mission. They called it Los Adaes and decided to make it the capital of the province of Tejas as well.

“it becomes very apparent very quickly that if war was to break out with Spain and France again, you can have 1000 soldiers here at Los Adaes, the French may only have a handful but they can rely upon 8,000 to 10,000 native warriors that will side with them over the Spanish. So by the 1730s, the garrison here is reduced to about 60 soldiers,” Mumaugh says.

With that, Los Adaes became little more than a gatehouse, in the middle of nowhere, marking the beginning of Spanish territory.

Because it was so remote, trade blossomed with the nearby French, although according to Gregory, doing so was strictly forbidden except for food.

“It was a perfect economy, though highly illegal,” Gregory says.

And the governors at Los Adaes turned a blind eye to the black market, because they benefited from it as well.

“In Spanish there’s a phrase – la mordida. It’s a bribe. So there’s a big mordida here from the governor, the governor is getting fat off it.”

The Spanish viceroyalty, unhappy with all these illegal shenanigans, started looking for reasons to shut the site down.

In 1762, they found one: The Treaty of Fontainebleau with the French expanded Spain’s territory all the way to the Mississippi River. The fort was no longer on the frontier and no longer necessary. Gregory says that was supposed to be that.

“People all abandoned it in 1773 by edict from San Antonio,” Gregory says. “The governor says you guys get up and get out.”

But many Adeseños had no desire to relocate to San Antonio, and people kept moving back. So, the Spanish burned Los Adaes to the ground.

And while that was bad news for the homesick settlers, Gregory says, “archaeologically that’s kind of good in a way, it left a footprint now with remote sensing that you can pick up pretty easy. And even if you can’t find a post, you can find the impact on the soil from the fire.”

That’s one reason why its so special. Los Adaes remains the most pristine archaeological site for a former Spanish Tejas mission. Even if you can’t see the ghost of this one-time capital of Texas above the ground here, its bones live right under your feet.

“You take the sod off out here and you’re in the 18th century,” Gregory says.

And its spirit lives on, too, not far away. A handful of Adeseños who refused to fully abandon their home among the pines set up another settlement a short way west of here, across the Sabine.

They called it Nacogdoches.