Hurricane Harvey was a seminal moment in the history of Houston. Five years later, where do things stand? Houston Public Media examines efforts to make the region more resilient to better prepare for the next big storm in Below the Waterlines: Houston After Hurricane Harvey.

Five years after Harvey, a solution to the flood threat from the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs remains a long way off

The most popular solution to the flooding threat from the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs is a massive underground stormwater tunnel. It would cost billions of dollars and remains more than a decade away from the start of construction.

Harris County Flood Control District

A subdivision on Langham Creek flooded by the Addicks Reservoir during Hurricane Harvey.

From Houston Public Media:

The Addicks and Barker Reservoirs protected Houston for more than 70 years, until Hurricane Harvey filled them and caused 25,000 homes and businesses on either side of their dams to flood. Since then, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its local partner, the Harris County Flood Control District, have been exploring ways to protect people on either side of the dams from major storms.

The two agencies appear to be converging on a massive infrastructure solution involving the construction of a stormwater tunnel deep underground that would be able to drain the reservoirs in an emergency. But even if they surmount all the political, financial, and bureaucratic hurdles in the way of such a project, the actual construction won’t begin for more than a decade.

What Harvey clearly showed was that Addicks and Barker are in drastic need of improvements. Christina Micu is an example of why.

Micu moved into her Canyon Gate neighborhood in Katy in 2012. When Harvey hit, she and her husband left town, thinking the worst that would happen was they’d lose power. Their eldest son had to work and stayed in the house. Then the Barker Reservoir filled and began flooding their neighborhood.

“He grabbed whatever stuff he could fit into a backpack and left,” Micu said. “And as he said, as he was walking down Mason (Road), the water was up to his chest, and he’s about 5’10”.”

Micu’s house took on two feet of water. After she was able to return, she no longer felt safe in the house, and so her family moved to Richmond.

Christina Micu’s house in the Canyon Gate neighborhood of Katy experienced two feet of flooding during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Credit: Christina Micu

“Literally every time it rains, I have a little panic attack,” Micu said. “I worry, like, ‘Okay, how bad is it going to be?’ Checking three or four weather stations at least four or five times a day.”

Micu joined a class-action lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which manages both Addicks and Barker. A federal court has ruled against the Corps and is now figuring out how much residents upstream of the dams, people whose homes flooded inside the reservoirs, should be compensated.

“The Corps needs to do whatever they need to do so that homes will not flood again,” Micu said.

The Corps built the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs in the 1940s, following a pair of deadly floods in 1929 and 1935 that inundated Houston from the west. That land west of Houston was then sparsely populated.

The plan at the time was to also build a canal that could empty the reservoirs in an emergency. But World War II intervened, absorbing much of the funding for construction. By the time the war ended and funding was restored, new housing developments had already begun on the land where the canal would have been built. That left the Buffalo Bayou as the only means to convey water out of the reservoirs.

For roughly 70 years, the reservoirs served their intended purpose of protecting downtown Houston. As Houston grew, though, new housing developments went up in western Harris County and Fort Bend County, many inside the land designated for the reservoirs.

In 2017, Harvey filled the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs for the first time in their history, and the rain kept falling. This meant the Corps made the tough decision to open the flood gates on the dams.

If they hadn’t, water might have spilled over and around the dams, eroding the dams themselves, and potentially creating a nightmarish urban tsunami that could have destroyed homes and businesses across downtown Houston and the Houston Ship Channel. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. But when the Corps did a controlled release of the water to avoid the worst case scenario, the historic volume of stormwater overflowed into surrounding, downstream homes.

Cheery Young, who lives downstream of the dams, had just returned from an overseas trip. She and her husband escaped by boat when the floodwaters came through her neighborhood.

“I left my house without bringing anything. No jewelry, no brush, no nothing, and not even with my driver’s license or passport,” Young said. “We just hurry, just left it, just running, and it just almost saved our life.”

Cynthia Neely and her husband escaped the flood downstream of the Addicks and Barker Dams by climbing the stairs to the top floor of their home until they were rescued by boat. Their wheelchair-bound neighbor from across the street was trapped in her apartment and drowned. Credit: Andrew Schneider / Houston Public Media

Not everyone was so lucky. “My neighbor across the street, she drowned in the Harvey dam release,” said Cynthia Neely, who lives in West Memorial, “and no, she didn’t drown because Harvey flooded her. She drowned because they released water from the reservoirs, and it flooded her apartment, and she was in a wheelchair, and she, bless her heart, she could not escape.”

Many of these victims, downstream of the reservoirs, are also suing the Corps. As University of Houston Law Center professor Tracy Hester explains, the Corps faced a dilemma.

“The Corps is being sued basically by the upstream owners because they waited too long to divert the water and by the downstream owners because they actually did divert the water,” Hester said. “It’s kind of a no-win proposition for them. The real ultimate solution is figuring out how to design systems to prevent that kind of awful choice when it does come up.”

The Corps has already taken the most basic steps it can to address the flood threat from the reservoirs. It replaced the aging gates on the Addicks and Barker Dams at a cost of $75 million. But that’s placing a bandage on a gaping wound. Solving the larger problem will require significant new flood infrastructure to keep those gates from ever facing another potentially lethal test.

The Corps’ Galveston District declined to comment for this story, citing time constraints.

In 2020, the Corps published an interim report known as the “Buffalo Bayou and Tributaries Resiliency Study.” That study determined two options are likely to protect the most people at the lowest cost: Widening the Buffalo Bayou and building a third reservoir. Those alternatives hit a wall of public opposition.

Wendy Duncan is president of the Willow Fork Drainage District, a state-founded entity that oversees drainage facilities over an area of roughly 5,700 acres in Harris and Fort Bend Counties. She’s also the co-founder of the advocacy group Barker Flood Prevention.

“The third reservoir is not going to be a viable solution, because parties are not willing to have that reservoir put on their land,” Duncan said. “Nor is widening the Buffalo Bayou downstream of the two reservoirs a viable plan for political reasons. People do not want their private property taken over.”

That leaves two options the Corps ruled out. The first involves deepening the reservoirs, so they can retain more water without backing up into nearby homes. Duncan’s Willow Fork Drainage District is part of a pilot project to accomplish that.

“Through a good working relationship with the Corps of Engineers,” Duncan said, “we identified a little piece of land – it’s actually about 400 acres of land – that is not environmentally sensitive. It doesn’t have a lot of wetlands on it. There’s not a lot of cultural resources on it. But it is an area that could start digging that reservoir deeper to provide additional storage for stormwaters when they come.”

While it is cooperating in that project, the Corps of Engineers said deepening the reservoirs alone is not enough to reduce the flood risk from Addicks and Barker.

“Ultimately, we need a way for the water to get from Addicks and Barker Reservoirs safely all the way to (Galveston) Bay,” said Augustus “Auggie” Campbell. He’s the executive director of the Association of Water Board Directors of Texas and the chair of Houston Stronger, a coalition of dozens of civic groups aimed at raising government funds for flood resilience.

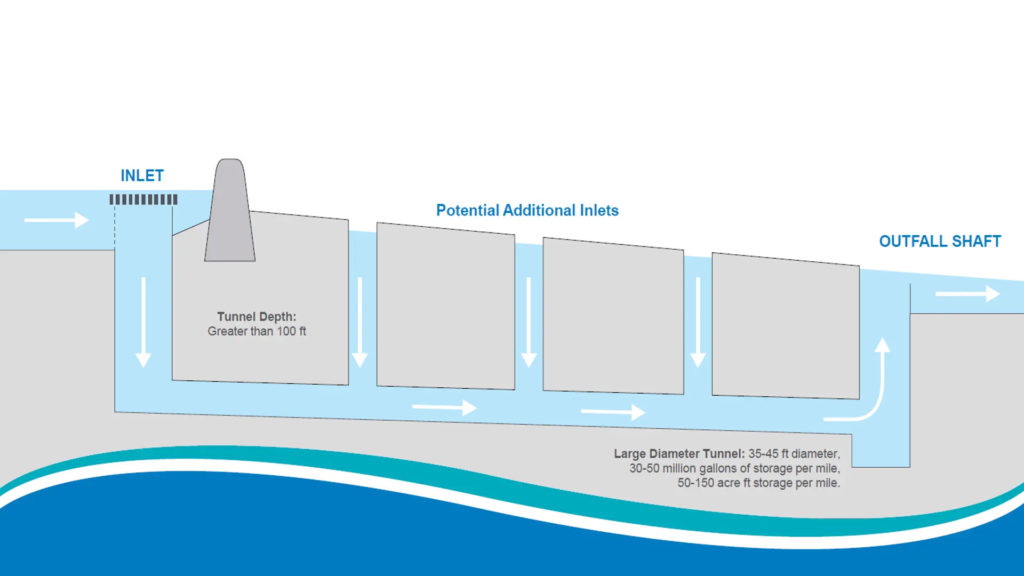

Houston Stronger is pressing hard for the second option the Corps initially discarded: The construction of a stormwater tunnel that would carry the water underground for miles, emptying into the Houston Ship Channel.

In addition to Houston Stronger, dozens of private individuals weighed in on the Corps study in favor of the tunnel option. Among them was Bill Cook.

“Well, it was a new experience for us,” Cook said. “We’d lived in that house for almost 40 years. And we’d never had water even on our street up until the day before our house flooded.”

Cook has become a bit of an expert since his Bear Creek Village home was flooded by the Addicks Reservoir. He’s now a flood resilience activist, and he doesn’t see how to fix the problem without a big project.

“I’ve been following that since the beginning. I had a lot of conversations with people both in Harris County and Army Corps of Engineers,” Cook said. “Storm tunnels are likely the only solution for relieving the two reservoirs during a major weather event.”

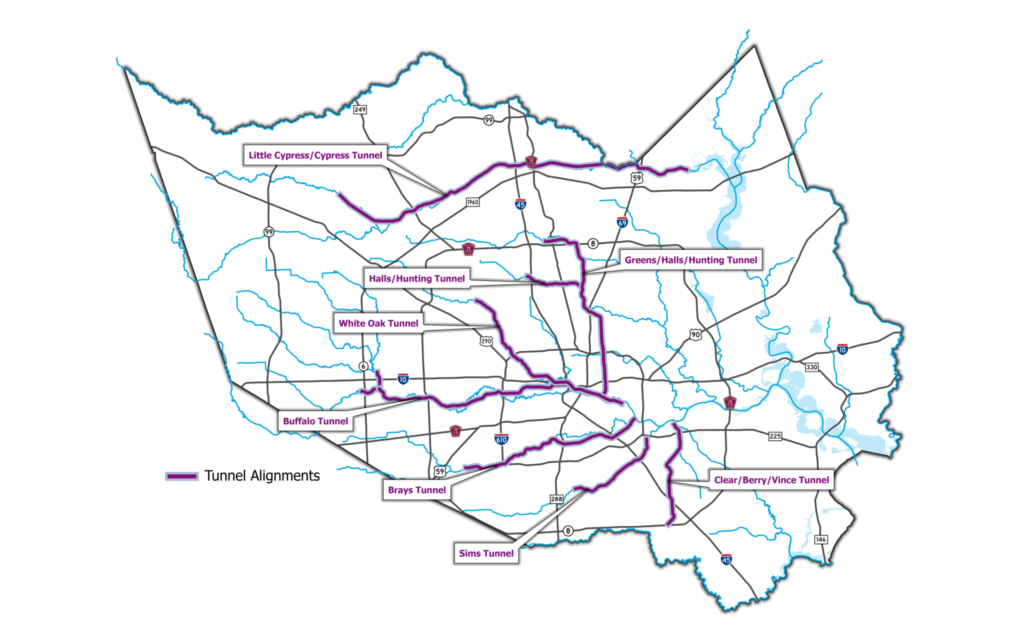

Map from June 16, 2022 Virtual Public Meeting on the release of the Districts Feasibility Study of Stormwater Conveyance Tunnels, Phase 2. Map depicts eight proposed routes of stormwater tunnels under and through Harris County. Credit: HCFCD

Several other Texas cities have used underground, large-diameter stormwater tunnels to reduce the risk of flooding, most notably San Antonio and Austin. But the Corps of Engineers said in its study that such a tunnel for the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs would be too expensive at $6.5-12 billion.

The Addicks and Barker tunnel option has other critics. Among them is former Harris County Judge Ed Emmett, now a fellow in energy and transportation policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute.

“I’ve always been skeptical,” Emmett said. “Just the gradient from Buffalo Bayou to the south isn’t very great, so how deep do you have to make that tunnel?”

The other issue Emmett identified was that there are already a large number of underground pipelines in the Houston area. “Digging a tunnel of that sort,” Emmett said, “you’d have to go so deep to avoid it, I think the cost just becomes astronomical.”

There are some indications that the Corps itself was divided on the question of a stormwater tunnel. Shortly before Colonel Timothy Vail, the then-commander of the Corps’ Galveston District, retired from the Army, Harris County Commissioner Tom Ramsey paid tribute to him in June.

“You were the extreme advocate for tunnels in Harris County, when so many people were running around, saying, ‘Oh, we can’t afford it. It doesn’t make sense,'” said Ramsey, a civil engineer by training.

The Harris County Flood Control District is doing a multiphase study on installing a network of tunnels – not just one – to reduce flooding. The Phase 2 report came out in June and estimates the tunnels would cost $30 billion. But that study also appears to rule out a tunnel to drain off the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs.

“I grew up in cold weather and stuff,” said Tom Maunder, a Montana native and longtime Alaska resident who moved to a Katy subdivision in 2013, unaware his home was inside the Barker Reservoir. “I’ve seen four foot of snowfall in a storm. I ain’t never seen almost four foot of water.”

The area around Maunder’s former home in the Grand Lakes subdivision of Katy, during the early stages of flooding from the Barker Reservoir during Harvey. Credit: Tom Maunder

At the time of Harvey, Maunder lived in the Grand Lakes subdivision of Katy. He watched the fire hydrant in front of his former home disappear one too many times when the Barker Reservoir flooded his street. When floodwaters filled his street again during Hurricane Imelda, he said he’d had enough.

“I have PTSD out of it. If we had heavy rains, I paced. I couldn’t sleep,” Maunder said. “I do not want to relive that.”

Maunder, who now lives in Richmond, said he’s in favor of the US Army Corps of Engineers taking any action that can shift the water out of the reservoirs in a hurry. That includes a stormwater tunnel.

“Tunnels were debated when they originally did the expansion of I-10, and, ‘Oh, no, we can’t spend that money,'” Maunder said. “But, you know, I don’t know how many billions of dollars of damages there were after Harvey. And putting something in when they put in I-10 would have been cheap compared to what they’re going to do now.”

Maunder was under no illusions that a tunnel would come anytime soon. “It’s going to be years before it’s ever active,” he said.

That’s if it ever gets built. Although the Harris County Flood Control District’s Phase 2 study appears to rule out a Buffalo Bayou Tunnel, Scott Elmer, the District’s assistant director of operations, insists such a tunnel is very much a live option.

“The Buffalo Bayou Tunnel is still an actionable tunnel alignment and is included in the Phase 3 potential tunnel system,” said Elmer. “All of the eight tunnel alignments are being proposed to move forward.”

Even with Harris County’s support, there are several hurdles standing in the way of tunnel construction, starting with money.

Congressional redistricting has just shifted the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs into Houston’s brand new Congressional District 38. But for the rest of this year, their communities’ voice in the U.S. House is Congresswoman Lizzie Fletcher. She’s determined to keep advocating for federal funding for flood infrastructure to make the reservoirs safer.

But Fletcher said that the $30 billion price tag is a problem, because the tunnels are competing for federal dollars with a huge number of other projects on the Corps of Engineers’ backlog. “These are big numbers,” she said. “And that’s why it’s so important to have community consensus about a path forward. And it’s also why it’s so important to really demonstrate the benefits, not just to our area, or one specific area, but to the region, to the state, and to the country as a whole.”

Harris County is hoping Congress will come up with some of the funding. But the county itself has to have some skin in the game, roughly $10.5 billion according to the federal Water Resources Development Act. The county might be able to share some of the cost with the state Legislature and other local governments, but county taxpayers would be on the hook for the rest. It’s far from clear they’ll agree to that.

If the money materializes, the Corps and the Flood Control District will need to cooperate to make the tunnel a reality. Scott Elmer says the Corps is coming around to the idea of tunnels, despite having rejected them before.

“I believe that the Corps and the Flood Control District and all federal and state partners all have the same goals in mind, and that is flood risk reduction for the residents,” Elmer said. “There’s always details that have to be worked through, but I do believe that ultimately, there will be some benefit and alignment between us and the Corps.”

Ruined furniture from Cook’s former home, awaiting removal.

Credit: Bill Cook

Addicks Reservoir flood victim and activist Bill Cook isn’t so sure. He’s spent years working with both the Corps and the District, and he said the two agencies are rarely on the same page.

“Because the Army Corps has been in a status of do nothing, take no action for many, many years on the reservoir. Harris County has been in the mode of action,” Cook said. “I think they’ll continue to have somewhat of an adversarial relationship on anything having to do with the reservoirs.”

But even if the Corps and the District are able to work together, that still leaves a third big challenge: Time.

“It’s going to take a while,” Scott Elmer admitted.

The Harris County Flood Control District, having completed its Phase 2 study, still has to finish a final Phase 3 study before it can start construction. That will take another three years. After that, assuming all the needed money is in place, Elmer said, “It will take about 10-15 years to go through the engineering, the right-of-way acquisition, the construction, and to deliver a finished product.”

HCFCD Illustration: Illustration from June 16, 2022 Virtual Public Meeting on the release of the Districts Feasibility Study of Stormwater Conveyance Tunnels, Phase 2. Illustration depicts how the proposed stormwater tunnels would function.

In other words, it could take well into the 2030s before a Buffalo Bayou Tunnel is built in the best of circumstances.

Reactions from people living in the path of the reservoirs are mixed. Landrum Wise lives downstream from them, and despite everything, he remains optimistic.

“Pandora left hope in the box,” Wise said, “and because of that, and because of the actions, particularly recently by the Corps, I do have some hope. It’s a long-term hope, but it’s a hope.”

Landrum Wise and his wife, Lynnea, standing amid ruined appliances and furniture they’d removed from their home after it was inundated by water released from the Addicks and Barker Dams during Harvey.

Credit: Landrum Wise

More common, though, is the reaction of Todd Banker. The Barker Reservoir filled his Katy home with more than a foot of water. He’s one of the test cases in the damages phase of the upstream homeowners’ class-action lawsuit against the Corps.

“I have little faith that the government can handle this,” Banker said. “They’ve had a chance to do something about this every decade for the last 70 years, and they haven’t done anything about it for the last 70 years. I mean, I’m not sure that this is enough, even enough for them to change that attitude.”

Tom Maunder is also downbeat that the Corps will make life better for his former neighbors within the reservoirs. “The Corps of Engineers is a government military agency whose mission is to save downtown Houston,” Maunder said, “and if you’re upstream, like we are, you don’t matter, period. And they’re going to have their comeuppance.”

Those feelings, anger and disappointment, are still fresh for a lot of people. And they’re going to face the ongoing threat of more flooding with each big storm that tests the limits of the Addicks and Barker Reservoirs. Cynthia Neely, who lives downstream and lost her neighbor to the flood, believes tunnels are potentially an answer, but she’s convinced something has to be done now.

“There’s not one solution,” Neely said. “There’s not one county or one city solution. It has to be multiple things that are all done and do them as fast as you can.”

If you found the reporting above valuable, please consider making a donation to support it here. Your gift helps pay for everything you find on texasstandard.org and houstonpublicmedia.org. Thanks for donating today.