From KERA News:

Toxic inhalants, flammable gases and explosive chemicals are just some of what rolls along Dallas-Fort Worth area highways every day. A simple road accident involving an 18-wheeler carrying hazardous materials could put dozens of people, if not whole neighborhoods, at risk.

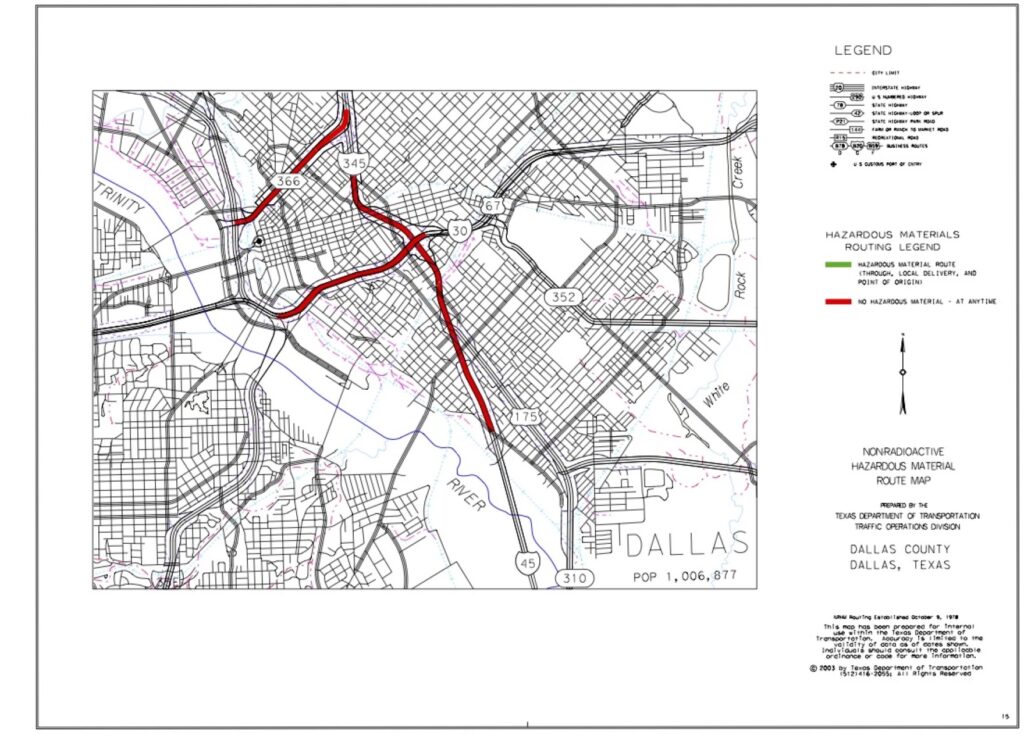

Trucks carrying volatile chemicals rumble down highways that were designated as “hazmat routes” in 1985, when the population of DFW was half the size it is now. At the time, large portions passed through sparsely populated areas.

Almost 40 years later, empty space has been replaced by businesses, residential neighborhoods — even schools and churches.

The hazmat routes are designed to minimize the chances of a mass-casualty event. They rely on truckers using them. But not all the trucks stay on those routes.

No one really knows how much hazardous materials pass through North Texas. And emergency personnel say they have virtually no way of knowing what’s being carried until an accident happens.

Trucks carrying hazardous materials are supposed to display placards that gives first responders some idea of what’s on board. But if a placard isn’t accurate — or has been obscured by fire or smoke – the threat may not be apparent.

And the threat is real. Trucks carrying hazardous materials have been involved in deadly accidents across the nation.

- In 2019 a semi-truck carrying empty propane tanks crashed into multiple other cars on I-35 near Denton. The truck and vapors seeping out of the propane tanks caught on fire, as did other vehicles. Three people were killed in the crash and three others were injured, according to incident and media reports.

- In 2020, a tanker truck carrying 8,500 gallons of fuel rear-ended a Volkswagen Passat that had stopped on a highway interchange in suburban Atlanta. The impact caused the tanker to rollover into four lanes of traffic and both vehicles caught fire. Both individuals died because of the crash, according to incident and media reports.

- And less than six months later on Valentine’s Day 2023, a tractor-trailer carrying over 3,000 gallons of nitric acid crashed along I-10 near Tucson. Reddish-orange fumes could be seen rising from the wreckage as the area was evacuated. The driver of the truck was killed in the collision, according to Arizona Department of Public Safety. Nitric acid is toxic if inhaled.

First responders and emergency planners say that errors in labeling hazmat materials – and truckers who fail to follow hazmat rules — can lead to a catastrophe. So can a shortage of people trained to handle hazmat emergencies.

“From radioactive waste to the most toxic chemicals that you can imagine all travel by truck transport through all our cities in the metroplex,” Grand Prairie Fire Capt. John Stevenson said. “It’s an obvious concern.”

‘It was a bomb.’

Grand Prairie Fire Department hazmat-trained firefighters respond to an overturned truck under State Highway 161 in Grand Prairie.

Stevenson is the special operations captain for the Grand Prairie Fire Department. The city of almost 200,000 sits 14 miles west of downtown Dallas and has eight hazmat-designated arteries running through it.

Stevenson recalls an accident involving a truck carrying hazardous materials about three years ago. A semi had rolled over while trying to make a tight turn under a freeway overpass.

Firefighters at the scene called the department’s hazmat personnel only after they encountered a substance leaking out of the overturned tractor-trailer.

“We got the shipping papers from the driver and identified the product as 85-percent phosphoric acid,” Stevenson said. “And he was carrying multiple 330-gallon totes in the back of his trailer.”

The chemical is much heavier than water. Stevenson said the driver didn’t secure the load properly and the weight caused the truck to roll over.

Hundreds of gallons of the corrosive leaked out onto the roadway. Firefighters on the scene tried to stop it from flowing into storm drains. Once hazmat personnel arrived they realized they had a much bigger problem than preventing the chemical from leaking into storm drains.

“As we were walking up to the trailer, the explosive meters started going off,” Stevenson said.

He says hazmat responders use what’s called a “5-Gas Monitor” that can detect different vapors and flammable build up in the air. The meters won’t tell you exactly what the substance is but will alert when the substance reaches an explosive limit.

Stevenson said the alarms immediately sounded and “we couldn’t figure out why.”

Stevenson said they had to reevaluate the situation. After some research they realized the volatile liquid had reacted with the wood and aluminum of the tractor-trailer.

The meters had detected the byproduct of that chemical reaction. The truck had filled with hydrogen gas.

“All you needed was a spark or a little bit more increase in heat, and it would have blown up that overpass of 161,” Stevenson said.

“It was a bomb. A giant bomb.”

Grand Prairie’s hazmat-trained personnel worked quickly to pump “positive pressure” into the trailer to ventilate it.

“What we did was we changed the atmosphere inside the trailer,” Stevenson said.

Stevenson says this is just one of many examples of emergencies involving hazmat transport.

Dan Kessler is the assistant director of transportation for the North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) and led the route study for the metroplex in 1985.

He says that certain reports — called commodity flow surveys — can give a more detailed look into what kinds and how much hazmat moves through an area. National data suggests that 5,000 to 10,000 shipments of hazardous materials come through the area per day, according to Kessler.

That said, there hasn’t been a flow study conducted in the DFW area in decades.

“That’s the one area that I have the greatest amount of uncertainty, is that we have not collected that data over the last several decades to give you an amount of how much that’s changed,” Kessler said.

Population growth: Then and now

(Large areas along what became Dallas County’s designated hazmat route were sparsely populated in the mid-1980s. But that has changed dramatically. Move slider to change the image from an aerial view in 1984 to 2020.)