From KERA:

Through a translator, Muzdha recalls that day. She asked that her last name not be used out of concern for her family.

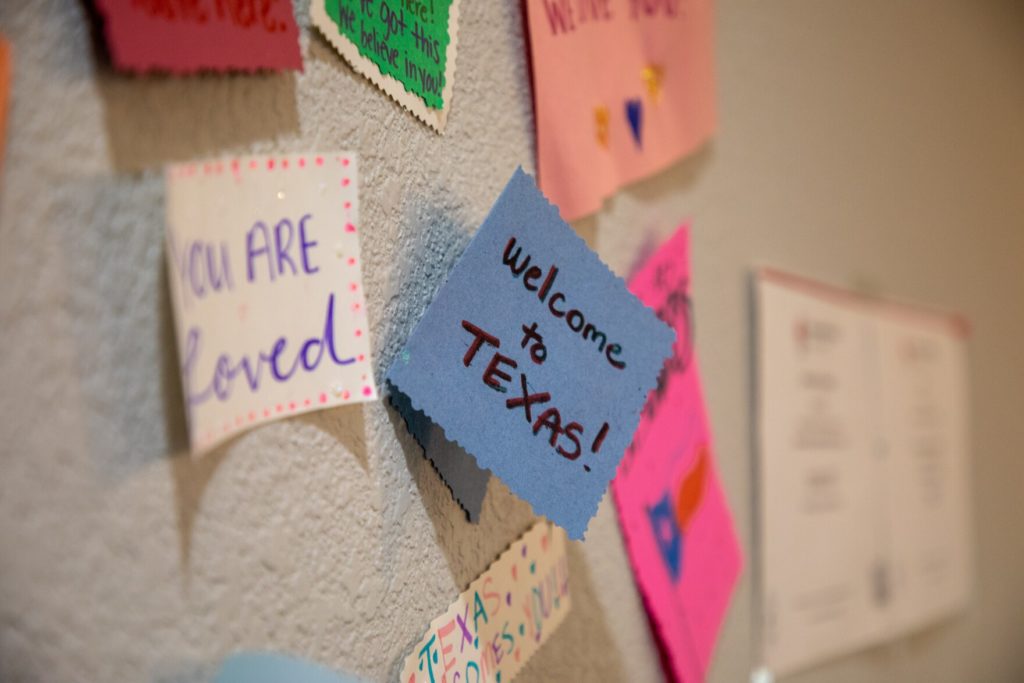

“A lot of people were there. Everybody was running into the airport to get evacuated…,” said Abdul Qahar Khan with DFW Refugee Outreach Services. “At the end, just only she was able to get into the airport. Her kids, mom…the family and everything was left behind….”

Muzdha, who worked for a U.S. government subcontractor, is among the more than 75,000 evacuees flown out of Afghanistan and brought to the U.S. after the U.S. military withdrawal.

Like many evacuees, her transition to the U.S. has been anything but easy. So far, she’s lived with three different families and said she’s had trouble reaching her case manager. Other challenges include learning a new language, finding housing and transportation and adapting to a new culture – all of it without her husband and two children.

KERA reached out to Catholic Charities, which resettled Muzdha, but a spokesperson said the agency couldn’t comment. KERA also contacted the State Department. A spokesperson there said staff would look into Muzdha’s case but also couldn’t comment on it.

Zeenat Khan, founder and director of DFW Refugee Outreach Services, has talked with a number of recent arrivals who say they’re struggling to adjust too.

The White House announced in September that Texas would receive 4,481 Afghan evacuees. That’s second only to California, which is expected to resettle 5,255 evacuees.

“I have three cases now where these women have been brought over here [with] half the family. I have a woman who’s here with her one kid and two of her kids and husband are left behind,” Khan said. “There’s no way these women can survive this alone.”

Faizanullah Saeed, 38, said he’s one of the lucky ones because he speaks English. But he’s concerned about his five children, ages 3 to 15.

“We are worried because since August I came from Afghanistan and they are not going to school,” he said when he was interviewed by KERA in December. “That’s the main issue that they have to provide us some educational programs that we can put our kids.”

Saeed and his family were staying in temporary housing. At the time, he said he had been told his children would be enrolled in school as soon as the family was moved to permanent housing. In the meantime, his children watched educational videos on YouTube.

Mikey Walizada, a combat interpreter for nine years, said he’s frustrated too. He’s staying in an extended stay hotel with his wife and sons, who are six and eight. He said he’s had trouble reaching his case worker.

“The main part for my wife and my kids is the English, so they can understand some English. I can do it. I can figure out everything for myself,” he said. “But for them, it’s important to leave the hotel for [however] long we’re going to be living in this hotel.”

Little advance notice

In September, the White House announced Texas would receive 4,481 Afghan evacuees. That’s second only to California, which is expected to resettle 5,255 evacuees.

Area resettlement agencies say they’ve been overwhelmed by the recent arrival of Afghan evacuees amid staffing shortages. Agencies aren’t receiving much advance notice of an evacuee’s arrival and they scramble to find housing and provide assistance.

To compare, Refugee Services of Texas had eight case managers at the end of 2016 when the U.S. admitted more than 10,000 Syrian refugees. At the end of 2021, the resettlement agency had four, according to Dallas Area Director Mark Hagar.

“The staffing challenges are there; they persist,” Hagar said. “But we’ve [also] had major support from the community, our national agencies in terms of funding and…offering to send a housing specialist.”

‘You should leave’

Muzdha said she didn’t want to leave her family in Afghanistan, but her mother thought differently.

“‘My daughter you should leave,’” Muzdha remembers her saying. “‘At least we will have one person survive from our family.’”

Now, all Muzdha does is think about them, especially her children ages 3 and 7. It’s difficult for her to talk about it.

“My 3-year-girl is left there. It’s winter,” she said. “It’s cold and they’re living in one of the most coldest place in Afghanistan,”

Bhavik Amaidas, managing partner at Suleiman Amaidas Rezai Law Firm in Irving, said he hates to paint a bleak picture, but the reality isn’t promising at the moment.

The biggest challenge for him as an immigration attorney is explaining to evacuees that they can apply for a humanitarian visa for a family member in Afghanistan. But that doesn’t guarantee their loved one will be able to follow through if the application is approved.

Those left behind face numerous obstacles, he said. They could be threatened by ISIS or the Taliban. They could go in hiding or not know if they can step outside of their home.

“Once an individual gets approval, they have to go to the nearest [U.S.] embassy and if they are hiding, it’s not like I can just catch a bus,” Amaidas said. “There is no embassy in Afghanistan at the current time.”

That means the person would have to travel to a nearby country and visit a U.S. embassy there. There could be a language barrier and then there’s the coronavirus pandemic with its own set of barriers.

“Because of the pandemic, because of the backlog, files are not processed immediately,” Amaidas said. “It takes awhile and there is a long wait.”

So far, hundreds of Afghans have been denied entry to the U.S., according to recent news reports.

As for Muzdha, she said she’s relieved not to live in a country ruled by the Taliban, but has an urgent plea for the U.S. government:

“Please help us. We helped you. We helped your mission in Afghanistan. We were the people who made it successful.”

Got a tip? Email Stella M. Chávez at schavez@kera.org. You can follow Stella on Twitter @stellamchavez.