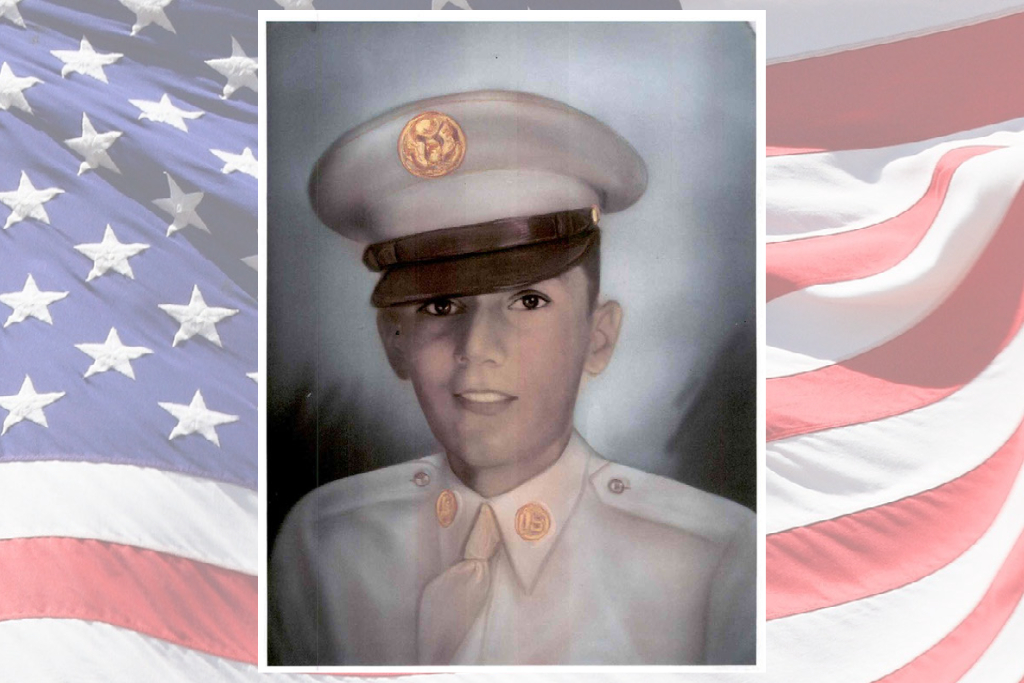

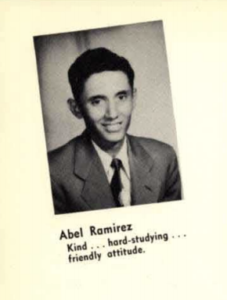

His 1951 high school yearbook describes Abel René Ramirez as “kind … hard-studying … friendly attitude.” He stares back at the camera with a shy smile.

Abel Ramirez grew up in the small town of Zapata, fifty miles southeast of Laredo. It’s cattle ranch and hunting country. Men wear cowboy hats and boots.

“He didn’t really like to work the ranch,” recalled Abel’s younger brother Romeo Ramirez. “His thing was more like engineering work – surveying. Before he went to [the] service he worked in the summer, he worked here at Zapata for the agriculture department surveying farmlands in the county. And then he went on ahead and joined the service.”

Abel’s early life had been marked by tragedy.

“My dad had been married before and he had Abel and then he had another baby,” Romeo Ramriez said. “And at two years of age, the second baby died and then his wife got pregnant again and had another baby and then both died. And so my dad ended up being a widow[er] with Abel at a young age. And then he met my mother and they got married and then we came along.”

Abel was much older than his two half-brothers, Romeo and Renato. Renato’s memories of Abel are faded.

“He was, you know, eight years older than I was so when I was when I was 10, I was probably a fourth-grader and he was a high school senior,” Renato Ramirez said. “And then, as soon as he graduated, he joined the Air Force and off he went. Six months later, he’s dead.”

Abel Ramirez was not quite 19 years old when he was killed on Jan. 24, 1951. It happened on an airfield in England.

“They were on duty at night, guarding the airport, and they got in their jeep. Somebody, a driver, dropped off the two relief guards and the two guys who were being relieved got in the jeep and were going back to quarters and that’s when they had this head-on collision with a deuce-and-a-half truck,” Renato Ramirez said.

“I was young kid, but I remember that [an] Air Force officer came to the house and gave my mom and dad the notice,” Romeo said.

The news was devastating. And circumstances meant the grief was drawn out even longer. A major nationwide railroad strike paralyzed the country.

“When my brother was killed in January, his body landed in New York, and there was a huge rail strike,” Renato said. “And it was 30 days before we got the body in Zapata. So for those 30 days between his death and his burial, it was holy hell. I mean, every day we had mourners come over to the house.”

Neighbors brought food to comfort them. But Romeo says his parents struggled to hold it together for that month.

“My dad never smoked until that time. He started smoking … because his nerves were just shot,” Romeo recalled. “And of course my mother was very supportive of him and tried to keep cooler and calm – try to pass that on to my dad. … My mom tried to shield us, Renato and I, from that suffering. But I could hear them at night talking after we were in bed and my dad shed many tears at night.”

These were the days of holding the wake in a family’s parlor.

“The day of the funeral, I remember the hearse picked up the the casket and we walked behind hearse from my house to the Catholic church, which was about, oh, four, five blocks away, I guess. And then we had the funeral, the mass and then we followed in vehicles to the old cemetery,” Romeo said.

His family was left to wonder: What would Abel Ramirez’s life have been, had he lived?

“I think he would have probably stayed in the service until retirement time or until he put in some years, and then I think he would have wanted to have been in the engineering surveying business,” Romeo said.

The people who would have best known Abel are gone now, 70 years later. But Romeo named his son Abel; and his son also named his son Abel. So perhaps a part of him will live on.

This Memorial Day, Abel Ramirez’s brothers will take flowers to his grave at the Zapata Cemetery, and they’ll make sure there is a small U.S. flag planted in the soil. A gesture to honor a man who died in service to his country.