Originally published by The 19th:

It was weighing on her — the prospect of starting a dream job in the middle of a pandemic, alone, her husband away 100 hours of the week helping fight COVID-19 inside a hospital infected by it. Her two boys were at home, without a teacher, with assignments, walking in on her work calls, interrupting her, passing her sticky notes, requesting — no, demanding — her attention every hour they were awake.

“If you come in, I will lose my job,” she told her 6-year-old in desperation, trying to keep him away.

Her husband was the hero. He was saving lives. She was the terrible mom — “the worst mom ever,” her sons told her — and the terrible worker.

In three months, Ellu Nasser watched as her white-knuckled grip on the labor force slackened. She drank more, before giving it up altogether in March. She told the dream job at a major consulting firm that her family responsibilities would get in the way of her work performance, so she couldn’t begin June 1, their agreed start date. She slinked back to the part-time gig she had consulting on climate change. And then in June, she gave that up, too.

For exactly one day, the relief was overwhelming. Then, worry.

“I kept wondering, ‘How long will the personal choices I made around COVID-19 hurt me permanently?’” said Nasser, 42. “I would like to be working for 25 more years. That’s a joy for me. My work is not separate from who I am as a person.”

Nasser was a stay-at-home mom for the first time in her life. She was collateral damage in what has become America’s first female recession.

For the first time since they began a consistent upward climb in the labor force in the 1970s, women are now suffering the repercussions of a system that still treats them unequally. Men are still the primary breadwinners. Women are still the primary low-income workers, the ones whose jobs disappeared when coronavirus spread. Mothers in 2020’s pandemic have reduced their work hours four to five times more than fathers to care for children in a nation that hasn’t created a strong caregiving foundation.

When the economy crumbled, women fell — hard.

This year, female unemployment reached double digits for the first time since 1948, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking women’s joblessness. White women haven’t been such a small share of the population with a job since the late 1970s. And women of color, who are more likely to be sole breadwinners and low-income workers, are suffering acutely. The unemployment rate for Latinas was 15.3 percent in June. For Black women, it was 14 percent. For White men: 9 percent.

All the while, women continue to earn less than men, with White women making 79 cents on the White male dollar, Black women making 62 cents, Native American women making 57 cents and Latinas making 54 cents.

What women in America are living now is the consequence of years of occupational segregation that kept them out of managerial positions, stuck in low-paying jobs with few safeguards like paid sick leave. When a third of the female workforce — the grocery clerks, home health aides and social workers — became “essential workers” this year, they were faced with difficult decisions about preserving their health or keeping their jobs. The rest found themselves more likely to be in positions that vanished overnight, like the housekeepers and the retail clerks, or on the margins, in the jobs at risk of never coming back.

Together, the losses threaten decades of steady, hard-won progress.

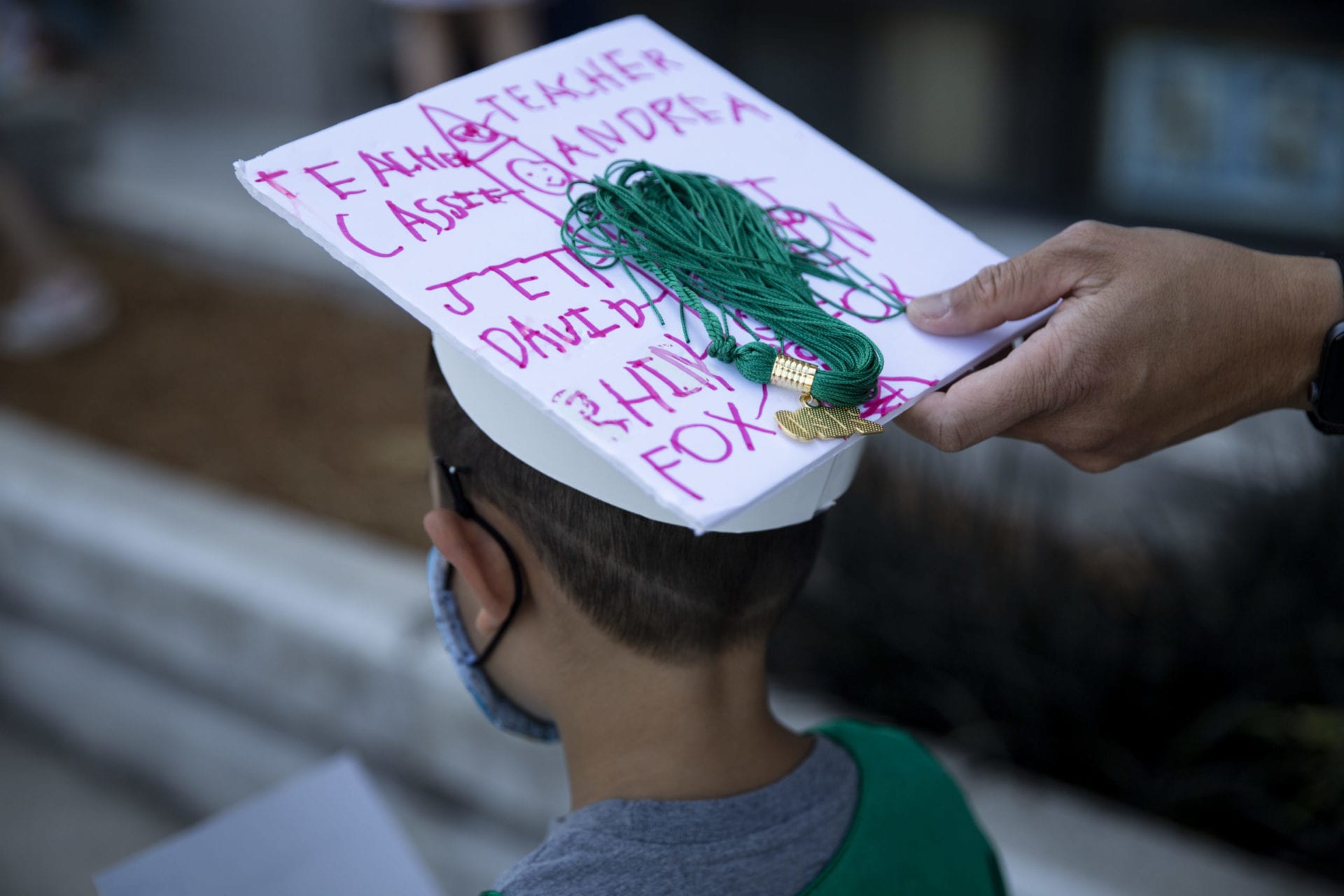

Nasser felt her loss most on the days when the constant run of doing dishes and cleaning up meals made it feel like her life was on hold. For the fall, she’s patched together some homeschooling with a retired teacher for her kindergartener and a handful of other kids from her Austin neighborhood. Her 9-year-old will return to private school.

Having a child care option is what helped her say “yes” when the call came in late July re-offering the position she passed up in June. She acknowledges again and again that she is luckier than most. She was able to make the difficult decision to leave the workplace — and then return — because her husband earns more than she does and they could afford to send their kids somewhere. Many women won’t have that this year.

“It’s a simultaneous feeling of guilt that we are able to do it,” she said, “and sadness that this is the situation we were in.”

The fall-out

In 1958, women made up less than a third of the U.S. labor force. It took them 30 more years to reach 45 percent, a pace of growth through the late 20th century that helped usher in the “most significant change in labor markets during the past century,” wrote Harvard economist Claudia Goldin.

Women’s gains in the labor market helped create an economy that, according to some estimates, is $2 trillion larger than it would have been if women’s participation levels remained where they were in 1970, when it really started to skyrocket.

For the past several decades, though, the gender split in the labor force has largely evened out. Then came 2009, a recession that hurt predominantly male-dominated jobs such as construction and manufacturing. Women overtook men as more than half of the labor force for the first time in history. It has happened again only one other time: In December 2019, when coronavirus was still but a distant headline in China, women surpassed men at 50.04 percent of the labor force.

It was a fleeting breakthrough.

Nearly 11 million jobs held by women disappeared from February to May, erasing a decade of job gains by women in the labor force.

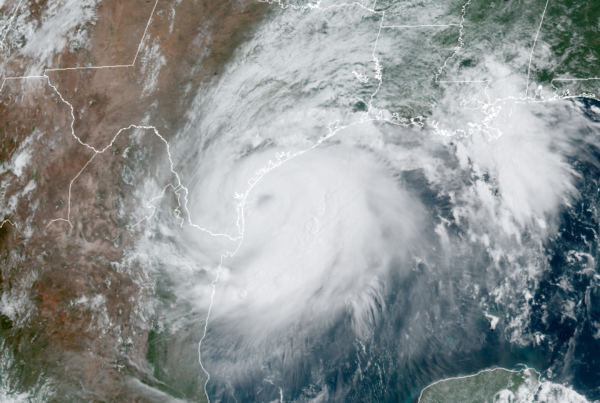

In June, women regained 2.9 million positions, but those jobs, which are largely in the hospitality field, remain insecure as coronavirus’ continued spread forces new closures.

We don’t recognize women’s roles and so we never ask, ‘Do women benefit?’

Heather McCulloch, founder and executive director of Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap

Depending on the length of this recession and when an effective treatment or vaccine for COVID-19 is developed, there is a real possibility many jobs lost by women will never come back, said Heidi Shierholz, senior economist and director of policy at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI).

As it stands, about 8 percent of women who have been laid off have zero chance of being called back to the workforce compared to 6.4 percent of men, according to an analysis by EPI. Another 4 percent expect to be called back but likely will not.

Those jobs at risk are anticipated to be in fields vulnerable to social distancing, positions like the one Cristina Aguirre Sevillano has held since she emigrated from Cuba a decade ago.

Aguirre, a housekeeper at Miami Beach’s Fontainebleau hotel, is already in a tenuous position: She was laid off from her full-time job in March, but when the resort reopened in June, limited work resumed. She’s been called back just a handful of times. Unemployment insurance has been predictably unreliable in one of the states worst at administering it. And even the job she took sorting fruit at a warehouse in Miami to patch together some work over the spring turned out to be a mistake.

On her seventh day sorting through crates, she went home with a fever. She couldn’t breathe well. That time, it was coronavirus incarnate that cost her a job.

Aguirre, 50, recovered, but “this has been the worst year we’ve had to endure,” she said. Her 23-year-old daughter, who lives with her, has also been laid off from a hotel job, and her husband is home recovering from a workplace injury. “I had never experienced something like this in the little time I’ve been in this country.”

She’s now wrestling with the idea that her reliable job, the one she clung to for 10 years while her pay inched up to $15.17 an hour — good by Florida standards — could suddenly go away completely. It’s a terrifying prospect for any low-wage worker, but particularly an immigrant.

“My English isn’t good,” she said in Spanish, implying her true question: Who would take her at even remotely the same pay?

As workers exit the labor force, skills will depreciate. Finding a job at the same level will become harder the longer they’re out of work. And because women will be most likely to be jobless, the gender pay gap will grow while overall wage growth will stall, said Gad Levanon, head of the labor market institute at the Conference Board, a nonprofit research group.

Employers will have their pick of employees, and that will bring salaries down. Low-wage workers feel that drop most intensely. Women make up nearly two-thirds of the 40 lowest paid jobs.

Support for minimum wage hikes — what some economists say is one of the best policies to close the gender pay gap — is already sputtering, too. In Virginia, for instance, the state’s first minimum wage increase in a decade has been delayed four months at the insistence of business groups worried about the virus’ impact.

The outlook is also bleak for those entering the job market or graduating college. The class of 2020 (and probably 2021) will enter a working world that pays less for the fewer jobs available. It’s a vastly different situation from the one graduates expected to be in at the beginning of the year, when the U.S. was at virtual full employment. Unemployment in January 2020 was just 3.6 percent — among the lowest recorded rates since the late 1960s.

According to a 2014 study of graduates from 1974 to 2011, students who graduate during a recession are likely to see their salaries decline by 10 percent in their first year at work, followed by dips of about 2 percent every year during their first decade in the labor force. Higher-paying majors, where male students are concentrated, will fare better, but lower-wage majors, where women predominate, will feel the impact harder.

“That’s something that will impact them for the rest of their career,” Levanon said. “It’s very, very hard to completely recover from that.”

William Spriggs, a professor in the Department of Economics at Howard University and a former assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Labor during the Obama administration, called it a “catastrophe.”

“We cannot continue to go through these economic spasms, where we lose a decade of job growth. And that’s what’s happening,” Spriggs said. “And so the people who have been left out, just as we get to the point where they get included, their resumes get stronger, their ability to withstand job losses gets better, then we send them back down the hill.”

A caring crisis

For women, in particular, hopes of climbing back out of this recession will hinge on one key, lingering question: What happens to the future of childcare?

The realities of the lopsided division of care inside American households has been on full display since work left the office and entered the home — for those who kept their jobs, anyway. Women in 2020 still take on the overwhelming majority of child care responsibilities, spending 40 percent more time watching their children than fathers in couples in which the parents are married and working full time, according to a study by economists at Northwestern University.

Then child care facilities started closing by the thousands. Since January, 1 in 4 child care providers have lost their jobs and as many as half of all child care slots could be lost with centers closing, according to a study by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank.

During a regular recession, women may have entered the labor force to supplement their partners’ lost hours; in this recession, with the child care safety net gone, that option is not even available.

When the layoffs started, Diana Niermann remembers some parents cried telling her they were out of a job and would have to pull their kids from daycare. Her Portland, Ore. facility, called the Kozy Kids Enrichment Center, closed on Friday the 13th in March — a bad omen if she ever saw one, she thought then.

An infusion of nearly $160,000 in a loan from the Paycheck Protection Program helped keep her from shutting down permanently, but the money was drained quickly to pay her staff, rent and to bring her facility to coronavirus regulation standards so she could reopen in June.

Of the 92 children Kozy Kids served pre-coronavirus, 17 came back. Much of Niermann’s staff, discouraged by future prospects in the child care industry, didn’t return either. Her director quit on re-opening day.

“I kept thinking in the beginning I was like, ‘Well maybe I’m not supposed to do this,’ but I’ve been through so much that I was like, ‘I’m not giving up, this is what I’ve done my whole life. This is what I believe in: good, quality care,’” Niermann said. “Child care doesn’t pay very much. We need to switch that.”

Moriah Ratner

So much of the reason behind that are policies that have often overlooked the needs of working women, said Heather McCulloch founder and executive director of Closing the Women’s Wealth Gap, an initiative working to advance policies that build women’s wealth.

“We don’t recognize women’s roles and so we never ask, ‘Do women benefit?’ McCulloch said. “We completely ignore or undervalue the role that women are playing, not just in their own families as breadwinners, but also as economic drivers of the economy. If women don’t benefit, the policies need to change because we’re all going to lose.”

Experts say coronavirus has helped many people understand, some for the first time, the challenges women have been juggling for decades. Child care is now a line item on multiple recovery proposals.

The Democratic coronavirus relief package, called the Heroes Act, proposes setting aside $7 billion through the Child Care and Development Block Grant that would allow providers to get emergency help for payroll, cleaning supplies and other equipment. The bill passed the House but has stalled in the Senate.

Senate Republicans released their own stimulus proposal in late July, a set of bills collectively known as the Heals Act, that would allocate more money to child care. The bills call for $5 billion through the Child Care and Development Block Grant and an additional $10 billion in “back-to-work” child care grants to help centers pay for additional costs brought on by the pandemic and to re-enroll children.

Democrats have called the plan “unworkable.” Both sides are meeting to discuss a joint proposal that could pass both chambers.

Advocates, who applaud the renewed attention on child care, also caution that neither plan as they stand now sufficiently addresses the estimated $50 billion infusion needed to stabilize the industry.

The issue is expected to continue garnering attention as the 2020 election draws near. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, who cared for his two sons as a single father after his wife and daughter died in a car accident in 1972, has released a caregiving plan that spans 10 years and earmarks $325 billion specifically for child care improvements, including free pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds; childcare tax credits of up to $8,000 for one child to low- and middle-income families; raises for child care workers; and incentives for businesses to build child care centers on their premises.

“If we truly want to reward work in this country, we have to ease the financial burden of care that families are carrying,” Biden said during a July speech in Delaware announcing the plan. “We’re trapped in a caregiving crisis, within an economic crisis within a healthcare crisis.”

But while workers wait for Congress to make a decision on child care — particularly ahead of the upcoming school year — many working mothers feel paralyzed.

Jenny Galluzzo, co-founder of the Second Shift, a platform that matches professional women with freelance and consulting projects, said the site has seen four times as many applicants since February as women try to make up lost work hours with part-time consulting work.

Beyond that, most women tell her they’re just waiting.

“You can’t plan ahead in any concrete way. And that stress manifests itself because you don’t know how to interact with the workforce. If you’re out looking for a job, how can you know what job to take because you don’t know in two months what your kids’ school situation will be?” Galluzzo said. “I worry for women because we’re taking an undue burden of all of the care and the invisible labor. I worry about all the strides we’ve made just being set back.”

What we are seeing play out is years of keeping women from positions of power where they could have turned their lived experiences into policy, said economist Olugbenga Ajilore with the Center for American Progress. It’s years of child care being a “women’s” issue — not a priority.

[Women] shape the culture and the way you do business, the way we think about things. That’s what we are losing with this.

Olugbenga Ajilore, senior economist at the Center for American Progress

“If we have more women in the economics field, if we have more women in Congress, child care would not be on the back burner,” Ajilore said. “When we think about women leaving the labor force, we’re not just losing economic output but we’re losing that contribution limit. They shape the culture and the way you do business, the way we think about things. That’s what we are losing with this.”

In many ways, though, coronavirus has served as a magnifying glass, bringing into sharper focus issues like child care that have long been ignored — and employers are responding. Companies that once resisted flexible work set-ups, and particularly remote work, are starting to embrace the idea.

“We have been fighting for the ability for women to work remotely and flexibly for years. It’s the number one thing women want for employment and companies have now been forced to see that that model works,” said Galluzzo, from the Second Shift. “And when the economy comes back and jobs are more plentiful and our kids are in school, I see this as ultimately a benefit because you don’t have to convince people any longer that [flexibility and being remote] works.”

“Can you have it all?”

Clara Toro

More than a decade ago, Mara Geronemus left a job at a big law firm in New York, moved to Miami Beach and started seeking out more flexible law opportunities. After her third child was born, she opened her own business doing remote work for clients across the country, a position that let her stay deeply involved in the lives of her elementary school-age children. She recently launched a working mom’s networking group called All Before Dinner and she’s finishing off a stint as the chair of the board of her children’s private Jewish faith school.

It was all part of the plan. Her husband stayed in his inflexible, but well-paid, position as an interventional radiologist.

When coronavirus sent her kids home, Geronemus said it was like watching her house of cards collapse.

She worked throughout the day to keep her kids on track with school responsibilities but found herself sitting down at the computer at 10 p.m. to start her own work. Often, her day wasn’t over until at least 2 or 3 a.m.

“I haven’t pulled all nighters since law school,” Geronemus said.

No matter how hard she tried, though, it wasn’t enough. When the school year was over, her 6-year-old daughter had more than 200 unfinished assignments.

“We can’t spend another school year or even another month doing things the way that we did it between March and June,” she said.

But when she starts to think about what would have to get cut, the calculation materializes quickly: “My husband is not quitting his job, he’s not leaving the hospital. My kids are not dropping out of school,” Geronemus said. “So, what gives? Probably my work.”

She worked hard to get here, to leave New York and plant roots in a community that she is deeply invested in, to be the mom her kids rely on.

When she shuttered her Miami Beach office this summer, it felt like it was starting to slip away. She was already halfway out.

“I want it all and I had found a way — and other women have found a way — for a short period of time to have it all or most of it, or have it all on some days or most days,” Geronemus said. “Now 2020 is forcing us to reconsider, I guess, saying, ‘Can you have it all?’”