From KUT:

Esteban Rivera got his first dose of the Pfizer vaccine at a small vaccination event in South Austin last week. Austin officials have had a mass vaccination site open for months now, but Rivera said he decided not to get vaccinated there because it seemed like a lot of work.

He said he saw how hard it was for his uncle to get an appointment early on.

“It was a lot tougher on him,” he said. “He was waiting there for a few hours. And so, he has a little bit more time than we do.”

Rivera has two young sons in elementary school and a lot on his plate. He said he didn’t have time to wait in line for a shot.

He and his wife eventually got vaccinated through their children’s school. No long line or appointment needed.

Paul Saldaña, the co-founder of the Austin Latino Coalition, co-hosted the event Rivera attended. He said mass vaccination sites in Austin have been leaving Latino families behind, so he’s been putting together these smaller events to get folks protected.

“I think we’ve done a poor job in making sure that we reached our vulnerable populations during this COVID pandemic and getting them equitable access to the vaccines,” he said.

Communities of color are falling behind

People of color in Austin are trailing their white neighbors when it comes to getting vaccinated — even though their communities have been hit the hardest during the pandemic.

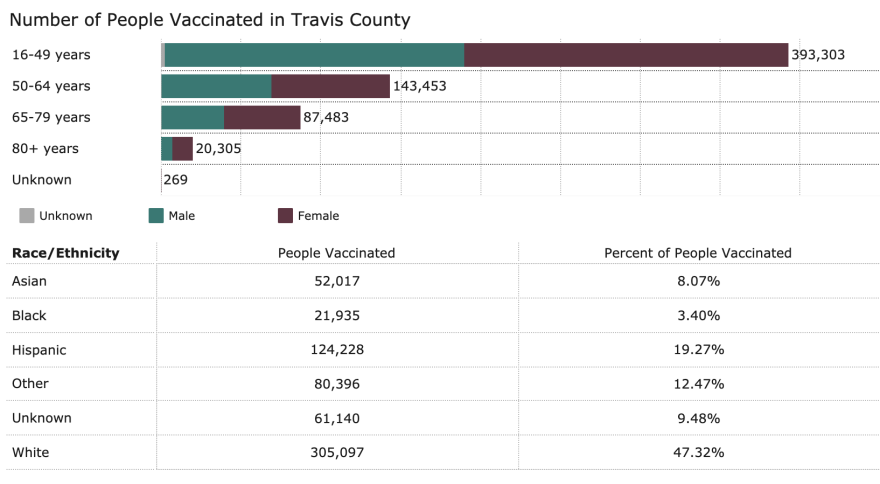

According to data from the Texas Department of State Health Services, as of Tuesday, only 3% of people vaccinated in Travis County are Black. The group makes up about 9% of the county’s population.

Texas Department of State Health Services

Meanwhile, 19% of the county’s vaccinated population is Latino — though they make up roughly 34% of the county’s overall population.

Austin Mayor Pro-Tem Natasha Harper-Madison said this was easy to see coming.

“There was an imbalance in COVID vaccine rates, imbalance of COVID vaccine distribution and testing – back when we were talking about testing,” she said. “So I don’t think that the equitable distribution we longed for is what we’ve seen play out.”

East vs. west

Harper-Madison said there are underlying issues that contribute to the big divide in access to health care between West and East Austin.

For example, West Austin — which is more wealthy and white — has more doctors’ offices, pharmacies and hospitals. It’s easier to get vaccinations through to communities who already have so many touch points within the health care system.

In East Austin, there are fewer touch points. As a result, that side of the city was poised to have fewer vaccine providers.

Travis County Judge Andy Brown said this is something he and other officials have taken seriously since vaccines were first getting shipped to Texas.

“Everybody that I talked to in local government was interested in trying to make it as equitable as possible,” he said. “Make the shots available to people east of 35, Southeast Travis County, Northeast Travis County, those areas.”

Mass vaccination sites

Austin Public Health set up mass vaccination clinics at the Delco Activity Center and in Dove Springs on the East Side. Brown set up a mass drive-thru with other counties at the Circuit of the Americas — also on the East Side.

Brown said he worked with CommUnityCare to make sure its patients — who are largely Latino and live in East Travis County — got vaccinated.

“Initially that effort really was exactly what we wanted,” he said. “I think we had 77% participation of Latinos the first week we did it. Somewhat lower the second week. And then the issues that have happened everywhere started raising up — of it’s just hard for some people to log on to make an appointment.”

And this hurdle — having to take time to sign on to a website and find an appointment — was particularly hard for Latinos.

Travis County Judge Andy Brown said one reason he opened a mass vaccination site to avoid getting penalized by the state for targeting specific communities.

Julia Reihs / KUT

Latinos make up the bulk of the Austin area’s frontline workforce. Some work multiple jobs and simply don’t have time to navigate the systems. Saldaña said about 20% of Latinos here don’t have access to WiFi or the internet.

“So anytime you have a system that’s based on the internet or WiFi, inevitably our people are going to have challenges,” he said.

Ideally, Saldaña said, the city would have targeted those hard-hit ZIP codes early on and offered walk-up vaccinations. No need for the internet or appointments.

Harper-Madison agreed that should have been part of the early vaccine effort, but said there are compelling reasons to have mass sites, too.

“Let’s be honest, you know, an individual location at a time doesn’t get us that many arms,” she said. “It does get us to people who are falling in the cracks, but it doesn’t get us that many arms.”

She said a combination of strategies is needed and the city needs to ramp up community-level efforts.

Barriers to targeted sites

Brown said another hurdle was the state. Early on, officials threatened to take vaccines away from Dallas because it planned to use a targeted approach to serve the city’s hardest hit communities.

“I think that led Austin Public Health into a position to where they felt that the state had really limited how they could focus the vaccinations,” he said.

In fact, that’s why Brown said he opened a mass vaccination site: He wanted to avoid getting penalized by the state.

But now, five months in, we have data about who got vaccinated at those hubs on the East Side. Largely people who don’t live there, Saldaña said.

“If you look at that data, the top five ZIP codes of people who received vaccines in Dove Springs were all predominately white areas west of 35,” he said. “And the same would hold true in the Delco Center.”

Closing the gap

Harper-Madison said health officials need to be more proactive with messaging and reaching out to those communities with lower vaccination rates.

“We can’t be passive about it,” she said. “We can’t just put out the word and hope the arms will come to us. We have to go to where the arms are in a lot ways. So, I think we have to be more considerably proactive – more full court press.”

Travis County Commissioner Jeff Travillion said there’s a bigger issue here, too.

He said Austin officials had the best intentions and wanted to make sure there was equity in their vaccination efforts, but they had blind spots.

“I don’t think that people have fully understood the types of things that low- to moderate-income communities have been deprived of,” he said.

There are stark differences in the needs of lower-income Black and Latino communities compared to other communities in Austin, Travillion said. Any plan to get those communities vaccinated was always going to have to address these needs.

Tavillion said Austin Public Health officials told Travis County commissioners the agency wants to close these gaps. Health officials plan to work with churches to reach Black Austinites, in particular, and there are events planned around Juneteenth. The city is also doing smaller events at schools.

For the most part, those mass vaccination sites have shifted to walk-up only — or have completely shuttered.

Brown said one of his latest projects is working with firefighters to take vaccines directly to apartment buildings and grocery stores on the East Side.

Travillion said he thinks local officials are starting to understand what kind of work needs to be done to close the vaccination gap between white Austinites and the city’s Black and Latino communities.

“I think many people have now received the understanding that there are huge structural differences that were created by public policy,” he said, “and, consequently, only public policy will be able to resolve them.”