From the Texas Newsroom:

Weekends at the Trinity Episcopal School in Austin are different these days.

Inside one of the campus buildings on a recent Sunday is a mix of parents and students. They are laughing with each other.

Most of them are Ukrainians who now live in Austin after fleeing their homes because of the war in their country.

“It’s incredible to have such a community here in Austin,” said Katya Sazonova, one of the parents. “The support that everybody is giving me … is just invaluable.”

The community Sazonova is referring to is the Ukrainian School in Austin, a special school created earlier this year to help refugee kids and their parents acclimate to Texas.

Sazonova and her two sons are part of the millions of people who have been pushed out of Ukraine due to the ongoing war. Those who have left Ukraine have sought refuge in other countries, including the United States.

The refugees who have ended up in Austin include school-age children. To help them with the transition, a group of Ukrainians created the school for them that meets on Sundays.

Natalya Garryshko helps lead the school. She told The Texas Newsroom it’s allowed the young Ukrainians to come out of their bubbles.

“Kids are a little bit isolated at home. They can’t make friends with American kids because they don’t speak any English,” Garryshko said. “So we decided it would be a good opportunity to open the Ukrainian School.”

Garryshko, a teacher herself, said the school also provides opportunities for parents to meet each other and create a community in Austin.

The war, the students and the teachers

The Ukrainian School is funded primarily through donations and the support of a nonprofit.

Weekend campers grab snacks after a long day of playing team activities during a weekend camp for Ukrainian child-refugees at Peaceable Kingdom on Sept. 3.

Here, students participate in ESL and Ukrainian language classes and arts and crafts and learn computer programming.

Most recently, students went to Killeen for a three-night camp at the Variety’s Peaceable Kingdom Retreat for Children.

Vironika Makhova, 11, said her favorite class was Ukrainian language.

“I really like it here because I can speak Ukrainian, not English,” Makhova said.

She came to Austin with her mother earlier this year after stops in Poland, France and San Francisco. Her dad had to stay behind in Ukraine fighting. This experience, in a way, has helped her understand the importance of learning her language, she said.

“When they say Ukrainian language is important, yes it is, because it’s our power because other Russians don’t know Ukrainian so they don’t know what you are saying,” Makhova said.

Even though teachers try to avoid talking about the war, it’s hard to not think about it, especially for the older kids.

Makhova has a video on her phone taken by her dad of their apartment.

Her room appears to have bullet holes in the walls. Some of her belongings were moved to a guest room.

When asked about her favorite thing in Ukraine, Makhova gets somewhat serious.

“To speak with my real dad — who is staying in Ukraine — on the weekends,” she said, holding back tears.

Hanna Mendyuk is one of Makhova’s teachers. She has also been directly touched by the war.

“My brother-in-law’s battalion got hit by a missile strike like five weeks ago,” Mendyuk said. “He survived.”

But every day her phone rings, she worries it will be a call with bad news about her brother-in-law, her sister, or a loved one still in Ukraine.

A safe space

Garryshko, one of the leaders of the school, said they avoid talking about the war at school because of how sensitive the issue is for many students.

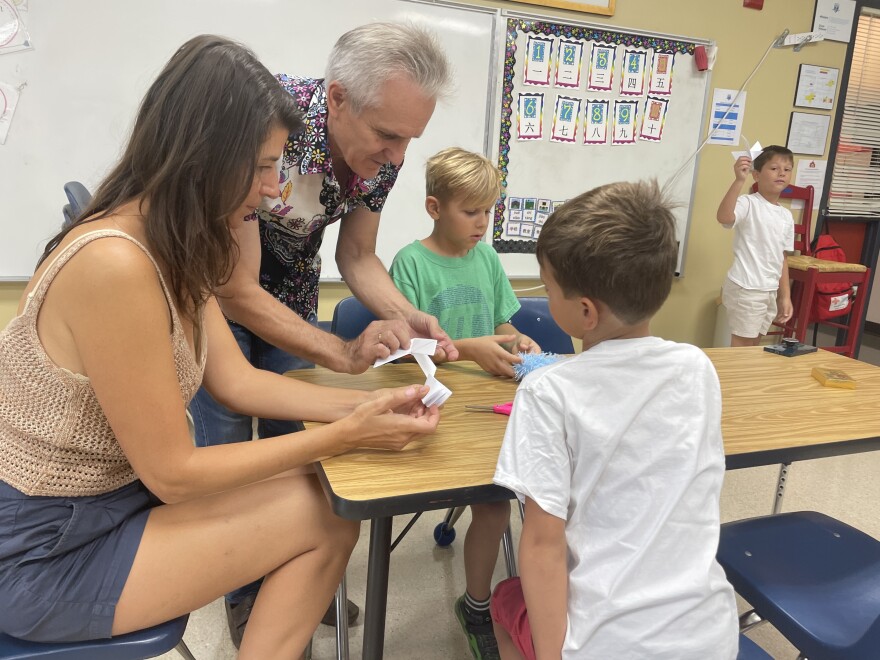

Teachers at the Ukrainian School in Austin help a student make a paper dove on July 31.

Sergio Martínez-Beltrán / KUT

“We don’t know every kid’s situation, what happened. Maybe some parent died in the war, maybe some have a dad left in Ukraine because he can’t leave the country,” Garryshko said. “So we try to make this place more like a happy place for them.”

And creating a safe space for these students has become therapeutic for some of the volunteers and teachers like Mendyuk.

“I can speak for all of us … we feel guilty like crazy, our families are there,” Mendyuk said. “What do you do with feeling like that? We do whatever we can. We do this.”