On April 25, 1980, President Jimmy Carter gave a televised address to update the nation on the 52 American hostages at the American Embassy in Tehran, Iran. The day before Carter’s speech, U.S. army special forces attempted to rescue them. But the mission failed, and eight U.S. servicemen died in a helicopter crash. President Carter took responsibility and vowed not to give up on the captive Americans.

“Throughout this extraordinarily difficult period, we have pursued and will continue to pursue every possible avenue for the release of the hostages,” Carter said.

The Carter administration faced more opposition than the president knew, though.

The hostage crisis was a key issue in the 1980 presidential election, in which Carter faced a re-election challenge from Republican Ronald Reagan. If the hostages were released before the election, Carter would get a big boost in the polls.

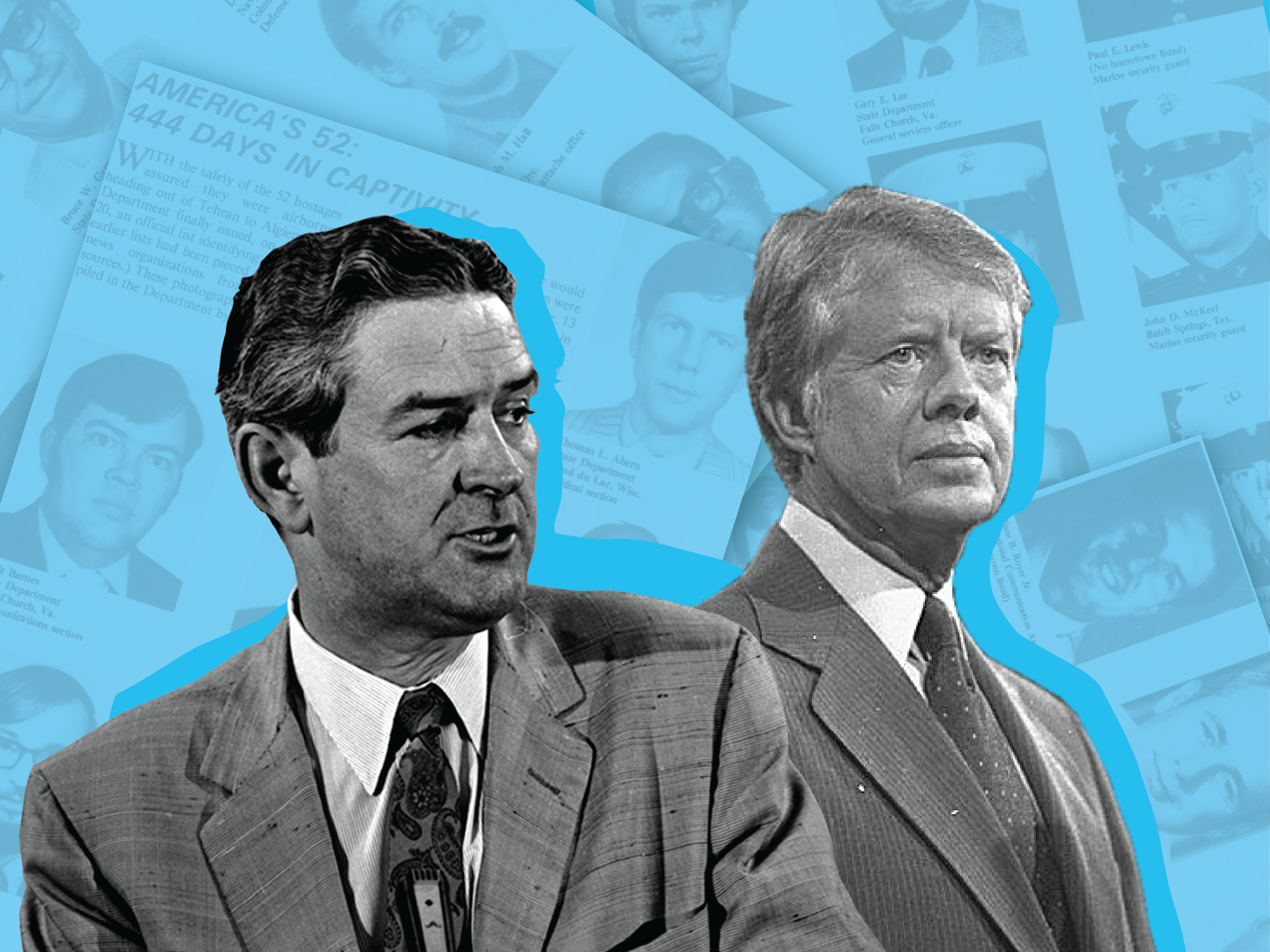

Which is why in July of 1980, Reagan ally and Texas political giant John Connally took a trip to the Middle East with a message for heads of state: Iran will get a better deal for the hostages with Reagan than with Carter, so it would be wise to wait until after the election to release them.

And that’s what happened. Minutes after Ronald Reagan was inaugurated in 1981, the hostages were released.

Connally’s involvement in the affair was a secret until just a few days ago, when the New York Times published an account of the story as told by Connally’s protégé: Ben Barnes, the youngest state lawmaker to ever serve as Texas speaker of the house. Peter Baker, chief White House correspondent for the Times, spoke to the Texas Standard about the story.

Listen to the story above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: How did you come to unearth this story after four decades? Did Barnes just call you up or what?

Peter Baker: Well, I’ve known Ben Barnes a little bit over the years. But he told a few friends over the years this story, and I think it had been weighing on him. It’d been something that he had been thinking about, and while he was watching some of the television accounts lately of President Carter going into hospice care, and seeing some of the images back from that hostage crisis back in 1980, he really began thinking this is the time to talk.

And so a mutual friend of ours – a mutual intermediary – mentioned that to me and I contacted him and he was ready to talk in a way I think he hadn’t really done before. He told a few friends. He told the author H.W. ‘Bill’ Brands from the University of Texas who mentioned this in a book of his – I want to be clear about that, a biography of Ronald Reagan in 2015. But it never got the notice at the time. But I think Ben Barnes thought it should and now he wanted to finally have the story told.

So what was Barnes’s role in this trip to the Middle East?

Well Barnes, as you rightly say, was Connally’s protégé – the two of them very close. Connally had just finished running for president himself. He tried to win the Republican primary nomination but lost to Reagan. And basically, he comes back to Texas and he says, ‘look, I’m gonna take a trip to the Middle East. Why don’t you come with me?’ Barnes says he didn’t really know what the purpose was. But they sit down in capital after capital in the Arab world, and what he discovered was that at each of these stops, Connolly was delivering that same message you just talked about to each of these leaders – ‘tell the Iranians not to release the hostage before the election. They’ll get a better deal from Reagan’ – and Barnes was shocked. He was a Democrat still, but he didn’t know what to say. He didn’t want to come out with that and tell everybody because he was afraid that Democrats would think he was a “Benedict Arnold,” in his phrase, for going on this trip in the first place. And so he basically has kept the secret for the most part for the last 43 years.

So what emotions did Barnes express when he was telling you all this?

Well, I think he felt regret. I think he felt, you know, some sense of relief in finally having the story come out. I think he wanted President Carter to know about this before he passed and my understanding is he was told about the article and has been informed about it now. I don’t want to speak for him, but I think that that has been an important moment for him, to bring some closure for it.

Is there any way to estimate what sort of impact Connally’s mission had on the hostage crisis? And for that matter, the 1980 election? You could even go further and say the trajectory of American politics.

Obviously, it was a big moment in our history that changed from Carter to Reagan. And we don’t really know. What is important to know is that Ben Barnes can talk about what he saw, right? And what he heard. What he was in the room for. What he can’t tell us is whether Reagan knew about this, for instance. Now, he does say that they met with Bill Casey, who was Reagan’s chief campaign chairman after the trip and filled him in about it. And that’s important because Casey has been at the center of a lot of suspicions over the years about any interactions between the Reagan camp and the Iranians. And he later became the Central Intelligence Agency director.

But you know, Barnes doesn’t know for sure if Reagan knew about it, and he doesn’t know if the message was ever passed on to the Iranians. He doesn’t know if the Iranians acted on it. We just know, as you pointed out, the results of what happened. They didn’t release them before the election. And we don’t know if there’s any kind of deal-making, you know, the original October surprise conspiracy theory, which has been investigated and to some extent debunked. But that theory had it that Reagan camp promised arms for Iran through Israel if they were to release the hostages. That’s not something that Barnes can tell us about.

But let’s just play it out for a second. You’re right about this: if, in fact, Connally’s message makes it to the Iranians and this influences their decision, it does change history because it is possible that, had there been a release of the hostages, it might have changed the dynamics for President Carter. He was actually keeping up with Reagan, and even ahead of Reagan until just a few weeks before the election. So it could have been a much different outcome.

But Peter, you said there has been this conspiracy theory, and has largely been debunked. But at the end of the day, we’re talking about a concerted organized effort to try to convince or get the message to the Iranians. We don’t know if that message was actually received and what the quid pro quo might have been completely. But does this not confirm the suspicions of the basic thrust of that theory that has been lingering out there for four decades?

Well, I think for President Carter, who has long thought something like this happened, it certainly seems to verify that something underhanded took place. No question about it. Connally’s message was that 52 American citizens should be held captive for longer than they needed to be for political reasons. That’s pretty remarkable. But again, as you say, we don’t know for sure what part that played in it. It’s important also to remember we talked about whether it would have changed the election. I mean, it’s important to remember that the economy was doing badly. Carter was, you know, troubled by inflation, unemployment – things that were holding down his popularity. So we don’t know for sure. But I think that a lot of people around Carter certainly believe that, had the hostages been released in October or anytime in September or whatever, that would have made a difference.

I was thinking about the last time a senior-level official, Robert McNamara, came clean years after Vietnam. And there was a lot of concern and a lot of criticism that he held those secrets for so long, and that the war could have been brought to a quicker end. Are there parallels here and, I wonder, does this rewrite history in a sense?

That’s an interesting parallel. You’re right. McNamara’s story is a fascinating one, the defense secretary who came to regret the war that he led. Really powerful story. And you’re right, there are a lot of people asking today, “well, how come the story wasn’t told 43 years ago, or at least sometime before then?” But it’s a reminder that history has a secret and there are things still to be unearthed. And eventually, people late in life decide to tell stories that they weren’t willing to tell when they were younger. Ben Barnes isn’t a young guy. I think he didn’t want, as he said, his obituary to have this in it. But he didn’t want President Carter to pass away without having had a chance to sort of make clean, if you will.