From Texas Public Radio:

The sun is setting as more then a dozen tiny bike headlights blink on. A group of cyclists heads towards downtown on their weekly Monday night social ride.

Rick Turnbill glides through traffic with a smile on his face, cheering on his fellow cyclists. He says he rides 120 miles a week and though he lives in Boerne more than half his miles are accrued in San Antonio.

“Who else can ride around the Alamo on their weekly ride?” asks Turnbill.

He rides recreationally and doesn’t commute to work, but he still believes the city needs more bike lanes to protect cyclists from motorists. Between 2011 and 2015, the number of adult bicyclists injured by motorists in Bexar County went from 20 in 2011 to 51 in 2015, or an increase of 145 percent. This is the last Trauma Report available from the county.

Right now Turnbill’s biggest worry is pedestrians walking.

“This is one of those areas that we have to create what we are going to do,” he says on a street filled with walkers. “We have to pay attention and be very courteous of pedestrians which that guy wasn’t,” Turnbill points to car driving by.

This bike ride could help Texas plan where future additional bike lanes and signs will go. That’s because Turnbill is one of the more than 84,000 Texas users of the smartphone cycling app, Strava.

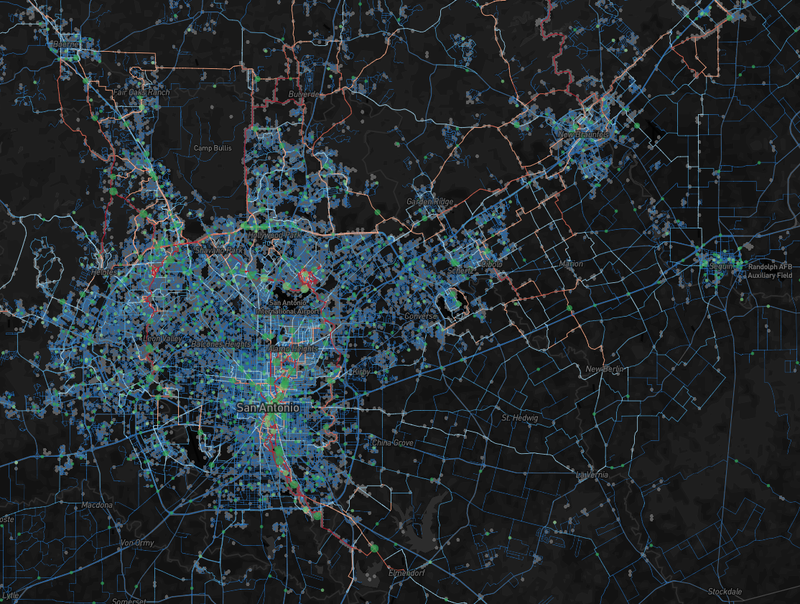

For the past few years Strava has been aggregating and anonymizing cyclist data then selling it to cities and states. Texas bought two years worth of data a couple months ago for an undisclosed amount.

Selling big data from an app is not new. Uber sells data from its drivers, but unlike cars, where bikes are going is largely an anecdotal game says Texas Department of Transportation Bicycle and Pedestrian statewide coordinator Teri Kaplan.

“There’s actually virtually no real data that’s consistently maintained for bicycles and pedestrians,” says Kaplan.

Going from almost no data to more than 200 thousand unique data points with routes is exciting, says Kaplan, “I think for some data geeks this could be Christmas. For me this is just a huge present under the tree,” she continues.

Demographic profiles, start and end points, time stopped at intersections, Strava provides planners with a cornucopia of information, but TxDOTs Bonnie Sherman says they still have to be wary.

“We do have to be cognizant of the biases of the data,” she says referring to the fact that Strava users tend to be pretty serious about cycling, so likely more athletic and affluent. They know that the app represents between 3 and 20 percent of the entire cycling community.

Kaplan, Sherman and other TxDOT staff are currently figuring out the best way to collect that data for a statewide database for cycling. Strava data will act as a way of validating much of it.

But local planners like Cecilio Martinez are still hungry for the information.

Martinez works at the Alamo Area Master Planning Organization and he has wanted this data for 18 months.

“This is great for us. We’re going to really be able to utilize this and get a better understanding of what’s going on within our system,” says Martinez.

The MPO is responsible for regional master transportation plans. Under the TxDOT purchase, MPOs, cities and other planners get the data for free.

Alex Caroll, also with the MPO, says this data will allow partners like VIA and the city to justify future bike infrastructure plans.

“It can be difficult to add bike facilities on the ground when there isn’t community support or if there is the belief that people aren’t going to be using it,“ says Carroll.

Some might remember three years ago the battle over bike lanes on South Flores. Once installed, area residents rallied to have them removed — believing they hindered traffic and weren’t used. This cost the city more money.

Rick Turnbill wraps up his ride at La Tuna in Southtown, and it doesn’t bother him Cyclists are being commidified and sold off.

“I think it’s the best thing you can do. Instead of guessing where to put the bike lane or the infrastructure, they can go see what’s being used.”

TxDOT says it will take around six months to fully integrate the data and learn how to use it.

More than a dozen cities and planning organizations across Texas attended a recent conference call on how to use it.