At the turn of the 20th century, curanderos, or Mexican faith healers, changed and connected communities along the Texas border in ways that still resonate today. They provided healing and spirituality to people in the region, including ethnic Mexicans, indigenous people and Tejanos. But their practices weren’t sanctioned by the Catholic Church, and they were especially looked down upon by the U.S. and Mexican governments.

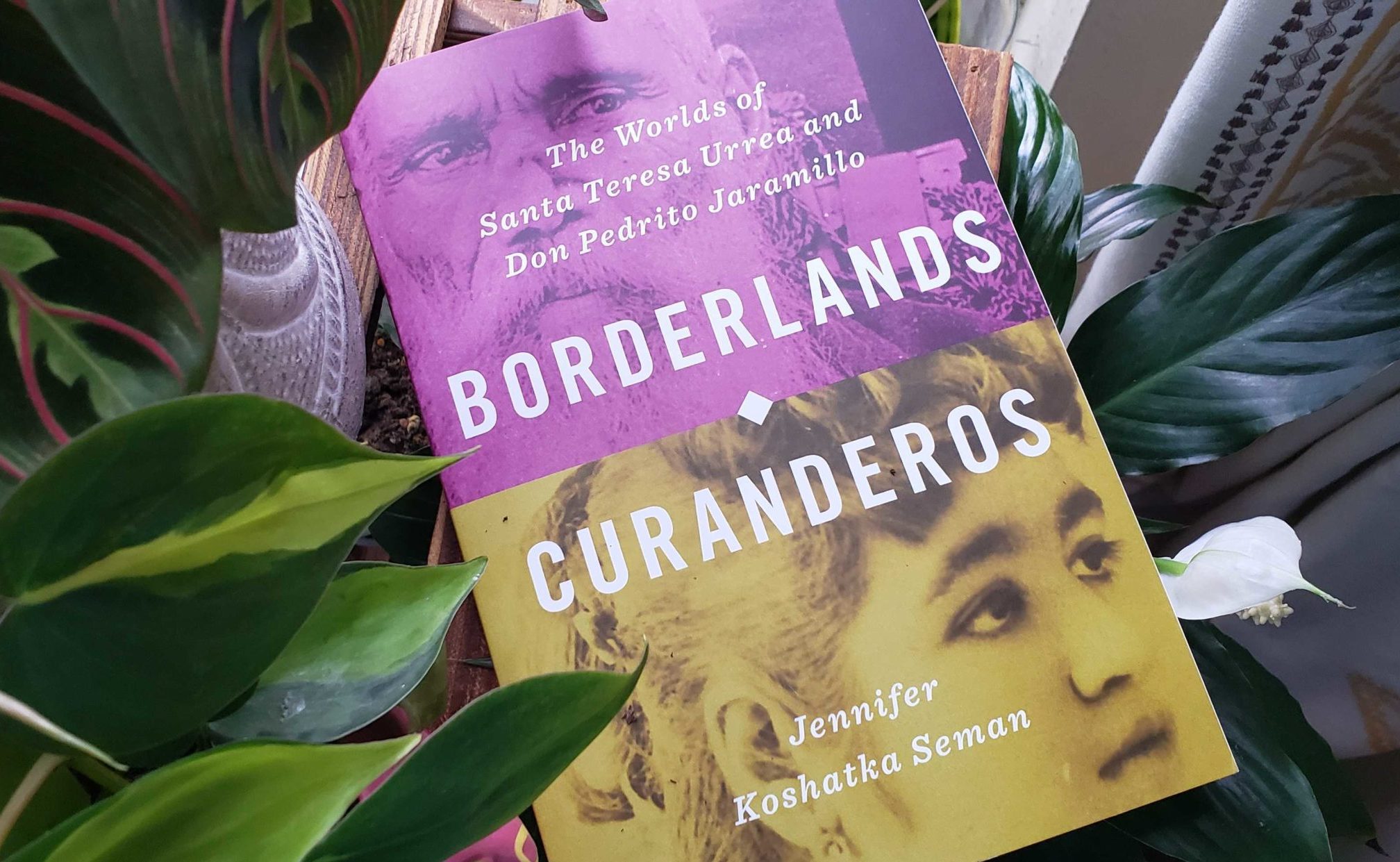

Author Jennifer Koshatka Seman says her book, “Borderlands Curanderos: The Worlds of Santa Teresa Urrea and Don Pedro Jaramillo,” shines a light on two faith healers, in particular, and their contributions to South Texas, El Paso and other areas along the border.

“[They] are significant and important to their communities, and not just kind of these fun curiosities, you know, which is in many ways … how they’ve been sort of presented in folklore and literature before,” Koshatka Seman said. “They were really instrumental in and supporting [of] their communities.”

Those who seek help from curranderos view their techniques as legitimate, and their talents God-given. The practice is an amalgamation of techniques from various local Indigenous cultures and African cultures, plus Catholicism, all dating back to the mid-1500s.

For outspoken Urrea, who was part Tehueco from Northern Mexico, Koshatka Seman says the spirituality of her practice was unusual for the late 1890s.

“She would say things like, ‘You don’t have to give up your land for the government’s,’ … you know, give these kind of informal sermons. And she would also say, ‘You don’t have to go to priests to confess your sins,” Koshatka Seman said.

She says Urrea had an “unorthodox” view of spirituality for her time.

“Based on what she was reported to have said, she was spiritual, she believed in Jesus, she believed in a lot of the the figures that she would believe in if you’re Catholic. But she was anticlerical, and so against the Catholic Church,” Koshatka Seman said.

Urrea was forced out of Mexico and made her way through El Paso, then went to the West Coast, performing healing on many people during her journey.

Don Pedrito Jaramillo, who came into prominence around the same time as Urrea, mostly stayed in South Texas. Koshatka Seman says he was beloved. But word of his work spread quickly, and he became a target of the somewhat newly formed American Medical Association, as well as the U.S. Postal Service.

The local post office noticed that more letters had gone out from Jaramillo than stamps that had been sold, which led to suspcion from the USPS. But Koshatka Seman says what was really happening was people would mail him letters with stamps inside so that he could write back with a cure, or receita, for what ailed them.

Koshatka Seman said suspicion of Jaramillo was rooted in pressure from the AMA on Texas’ medical association and physicians to “ferret out these alternative kinds of healers.”

Jaramillo was later accused of using the mail for fraudulent purposes, and was defend by League of United Latin American Citizens lawyer, Jose Tomas Canales, known as J.T., who was famous at the time for trying to hold the Texas Rangers accountable for acts of violence against ethnic Mexicans.

“He defended Don Pedrito [Jaramillo] and got him off, and basically he proved in his own words, he said something like, ‘I got him off of all the charges because I proved that he never charges any money for his cures. So there was no fraud taking place to me,'” Koshatka Seman said.

Canales’ work with Jaramillo was also personal. His own mother sought healing from him.

Today, in Falfurrias, Texas, there’s a shrine honoring Jaramillo with prayers for him on Post-Its, and Urrea continues to be celebrated in El Paso.