This story originally appeared on Houston Public Media.

At a River Oaks Chamber Orchestra concert in Houston, the musicians are in the middle of performing Haydn’s Symphony No. 6. In the audience, a couple dozen people have their heads bowed, staring at their smart phones.

Anyone who’s ever been to a classical concert knows this is a major “no no.” Usually, one of the first announcements made is to tell people to turn off and put away all mobile devices.

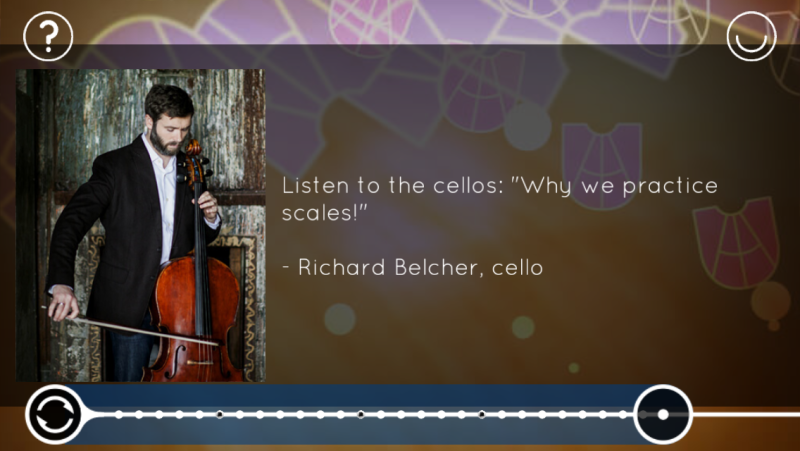

But in this case, concert goers are invited to use them. That’s because ROCO is testing a new mobile app called Octava, which delivers program notes in real time during the concert. It includes a mixture of historical tidbits and comments from the musicians. For example, during the Marcus Maroney piece, just before hearing the velvety tones played by clarinetist Nathan Williams a banner pops up with his picture saying, “I feel like I’m evaporating.”

ROCO founder Alecia Lawyer learned about the app through an article sent to her by a friend.

“I immediately friended them on Facebook and tracked them down,” she says, adding that she’d like to “ROCO-ize” it.

That’s how she became acquainted with Linda Dusman and Eric Smallwood, the app’s creators. They’d tried it out with the orchestra at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, where they’re based, but never with a professional orchestra.

Until now.

At ROCO’s rehearsal on the morning of the concert, Dusman is in the balcony, sitting on a stool in the little cubby where the organist usually sits. In front of her are an iPad and a binder with a musical score. During the performance, she follows a musical score with cues written in.

When the orchestra gets to a particular part of the score, Dusman taps a number on her iPad that sends the notes to the app.

Once the app is launched and started, the user is greeted with a colorful image beside a brief note about the first piece on the program. When Smallwood was creating the design, he made it so the screen is dimmed just enough with the intent of not creating a distraction. It also goes dark between the pop up notes. “We’ve sort of inverted the usual model of smart phones, which are doing everything to grab your attention at every moment,” he says. “And we sort of purposely went the opposite direction.”

Dusman says they haven’t yet established a concrete funding model for using Octava, which is free to download. They’re hoping that orchestras will subscribe so they can offer it for free to the audience, which is what ROCO did.

Groups elsewhere have started conversations with Dusman and Smallwood, but they’re waiting to see how it works with others first. They’re usually met with the same questions and concerns.

“The main concern has been about offending subscribers,” Dusman says. “You don’t want to offend your subscription base by having a distraction of somebody beside you using their phone.”

Which is why Lawyer designated a special section of their venue just for people who chose to use Octava.

After the ROCO concert, one audience member, Mary Bacon, is getting ready to put her smartphone away. The petite, gray-haired woman was one of the people who used Octava during the performance. On a scale of 1 to 10, (with 1 being the worst) Bacon says her tech knowledge is probably a 3, but there were some high school kids on hand to show her how to use the app.

“I didn’t know anything about any of the steps and so it looked intimidating,” Bacon says. “But it looked like something I really wanted to do.”

Her favorite part? “I believe it was the clarinetist who made some comments about how he felt playing it … and I liked that.”