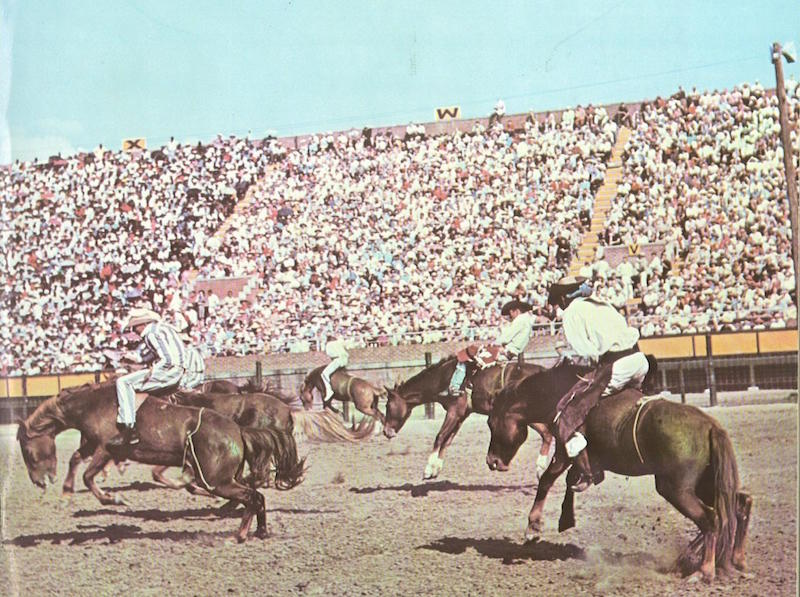

In a time before reality TV competitions like American Ninja Warrior, more than 30,000 Texans would show up on Sundays in October to watch prisoners put on a death-defying rodeo show that would make professional cowboys think twice.

Underlying the spectacle of the Texas Prison Rodeo, which during its 50 years evolved into an entertainment event complete with superstar guests like John Wayne and Johnny Cash, were many of the civil, political and criminal justice issues that propel our conversations today – explored in depth in the new book, “Convict Cowboys: The Untold Story of the Texas Prison Rodeo.”

Mitchel Roth, author of “Convict Cowboys” and professor at Sam Houston State University, says the man who ran the state prison system pitched this idea as wholesome entertainment, but it wasn’t just fun and games. It was a way for prisoners to cover costs of health care and other necessities, because lawmakers wouldn’t.

“If they needed new dentures or if they needed a prosthetic limb, they’d have to come up with the money on their own,” Roth says.

It came about during the Depression, Roth says, both as a means of entertainment and income. The prisoners were “as much for it as the administrators were,” especially because they would be able to earn extra commissary money.

“It became kind of the only time of year that there was some camaraderie between the keepers and the kept,” Roth says.

A huge part of the appeal for attendees, Roth says, was the spectacle – prisoners serving life sentences, often perceived to be dangerous, riding untamed, wild horses.

“It was like NASCAR racers going hoping for an accident,” he says. “People came and they were expecting to see people putting their lives on the line. Consequently, you had lots of people getting injured at each rodeo.”

These rodeos took place during Jim Crow and Roth says it was “probably the only non-segregated sporting event in Texas at the time.”

“You had black and white inmates in the 1930s competing in the same arena together,” he says. “They were kept separately in the stands.”

As a way to attract larger crowds, the administrators who planned the event made the events bigger and riskier than they would be at a regular rodeo.

“Instead of one bull rider, they had ten bull riders at the same time leaving the chutes,” he says, “which made for craziness in the ring. They tried chariots, they brought in parachutists.”

Roth says by the 1970s, the prison officials weren’t able to get enough liability insurance for the event, which meant they could be sued by injured participants. A prison in Angola, Louisiana, still holds an annual rodeo, Roth says, but other similar events have all but disappeared.

Post by Hannah McBride.