From Texas Public Radio:

Karina and Hipolito Mojica’s 1998 wedding on the El Paso border sounded like the script of a movie.

“She was walking on the bridge. People were beeping their horns, beep, beep, beep beep,” said Hipolito, an ER nurse who also served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps.

Karina recalled that she ran through the long line of cars in the rain, getting her wedding dress drenched.

“And I remember all the cars saw me,” she said. “And they were cheering.”

Against all odds — traffic, rain and even a hailstorm — the Mexican bride reached her American groom, who waited for her on the border city’s international bridge.

But their love story didn’t have a perfect finale. The couple has had to live apart because of the intricacies of U.S. immigration law.

As the Biden administration works to create a pathway to citizenship for millions of unauthorized immigrants, the Mojicas hope Congress will also pass a simpler bill to help immigrants seeking to legally reunite or reside in the U.S with their American spouses and families.

“Holidays are always really extremely sad,” Hipolito said, explaining that the couple and their three daughters have to decide between seeing each other in Mexico or spending time with his relatives in the U.S. “Because of our separation, and because of the law, we can’t be like everybody else. And it’s heartbreaking.”

In 1996, then-President Bill Clinton signed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act. Its provisions were sweeping, and it altered the course of life for families like the Mojicas.

“They made it easier to deport people, harder for people to come into the country, harder for people to fix their immigration status,” said Nancy Morawetz, a professor of clinical law at New York University. “They created a situation in which there was no longer basically a line for somebody to get on to to fix their situation.”

For Karina, it meant one mistake left her banned from the U.S. In 1997, Karina lived in Ciudad Juarez, and her friends urged her to go party with them across the border in El Paso, even though she didn’t have a visa or permit.

“I remember that somebody, my friend, told me, ‘you just can say that you are an American and that’s it,’” she said.

She joined them in a car and tried to get through the border checkpoint, where her friends presented their IDs.

“I was so nervous, because I just have to say I am American,” she said. “I said it, but with nervousness.”

The U.S. officer at the bridge noticed, so she never made it through. Karina said the officer gave her a paper barring her from the country for five years.

When Karina and Hipolito later met, the couple figured she could apply to enter the U.S. legally once the five years passed. That’s why they got married at the border.

“I thought that it was important to have a United States marriage license, I thought that would have some weight,” Hipolito said. “I knew she had an immigration problem, but I didn’t know how serious it was.”

When they gave it a shot, the consulate told them Karina was inadmissible because she misrepresented herself as a U.S. citizen.

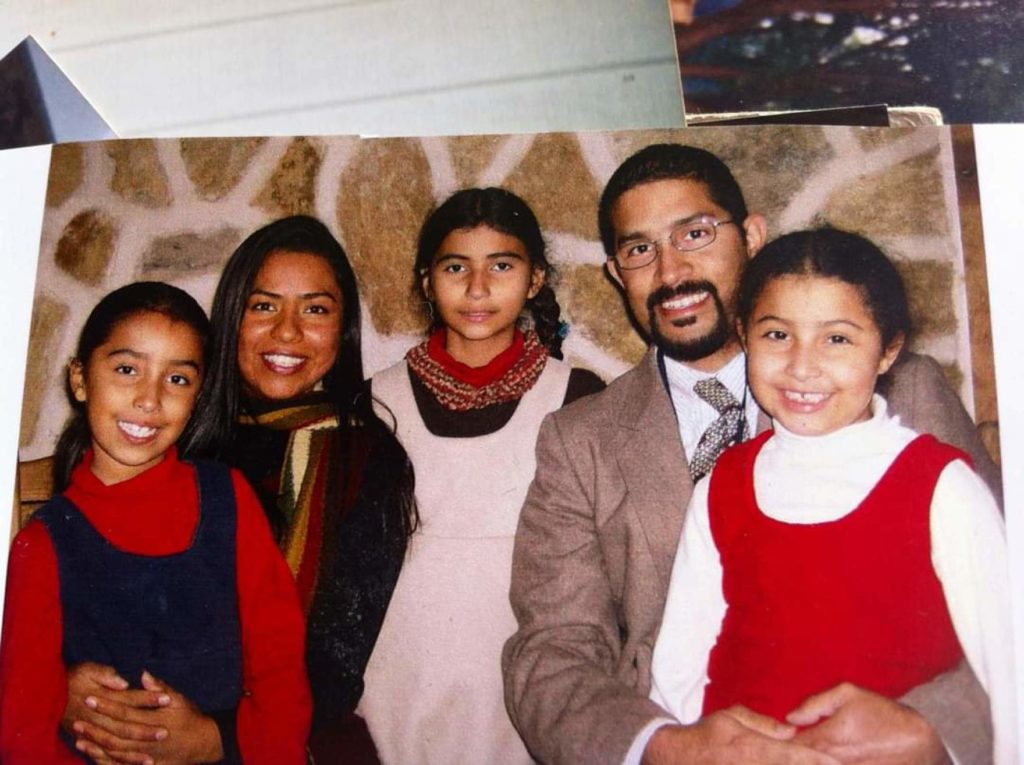

A family photo of Karina and Hipolito Mojica with their daughters. The family has had to live apart, split by the Texas-Mexico border and U.S. immigration law. Courtesy Of Karina Mojica

Morawetz said lying about U.S. citizenship had already been grounds for excluding someone from entering the U.S. or gaining a legal status, but the 1996 immigration reforms made it harder to ask officials to waive those laws.

“They added a new provision about any misrepresentation about citizenship, and then they created an extremely narrow waiver for that provision,” Morawetz said.

It has penalized Karina and many more for their mistakes.

“This is a huge problem, for example, when people get driver’s licenses, there’s often a checkbox for getting registering to vote or something like that. And in small print it says you certify you’re a citizen, and sometimes people have checked all the boxes without quite realizing what they were doing. But they are considered to have falsely represented themselves as citizens,” Morawetz said.

More broadly, changes to immigration law also made it harder for people like Karina to appeal their cases. Congresswoman Veronica Escobar of El Paso wants to change that.

“The immigration system in general has not had an emphasis on keeping families together. And in my view, and in the view of many others, that should be a fundamental component of our immigration system,” Escobar said.

The Democrat has reintroduced the American Families United Act, previously filed by her predecessor Beto O’Rourke.

“What the bill seeks to do is simply to give discretion to the federal government, so that they can review on a case by case basis who could be eligible and worthy of reunification under our immigration system or who should not,” Escobar said.

It would “plug a hole in the existing waiver system for spouses of U.S. citizens” and could help reunite more than 600,000 spouses separated by deportations or rejected immigration applications since 1997, said Randall Emery, treasurer of the advocacy group American Families United.

“It’s an issue that is sometimes overlooked in the immigration debate, because there’s an underlying assumption that if you marry an American citizen, your spouse would be a citizen,” Emery said. “But in far too many cases, that isn’t true at all.”

Escobar said she has also outlined the legislation for the Biden administration, which has promised an immigration overhaul, but it’s still unclear whether it will also address the issue and others created by the 1996 immigration reforms.

“My hope is that we are able to institute really even far more significant reforms when it comes to adjudicating immigration cases,” she said. “But this bill, to me, represents a very important and frankly, in many ways, an easy first step, this should be absolutely uncontroversial.”

Karina and Hipolito hope it will allow their family to live under one roof in the U.S.

They have lived across the Texas-Mexico border in cities like Eagle Pass and Piedras Negras to remain close as Hipolito works as a nurse in the U.S. and Karina runs her business as a health coach in Mexico. But it’s taken a toll on them. Hipolito says he was once kidnapped while traveling to visit Karina in Mexico, and more recently, had to recover from COVID-19 alone. Karina says she’s suffered from depression.

“I tried to have my life and advance in my career, in my job to be a productive business woman. But inside of me, I feel sometimes alone,” she said. “I pray that my situation can be fixed in this new administration.”

If the legislation passes, they may finally celebrate moments like their wedding with all of their family, and they may travel. Hipolito said he would also like to complete a medical residency to become a U.S. doctor without worrying about leaving Karina behind.

Karina said she wants to view the museums and landmarks of Washington, D.C. She said she fell in love with U.S. history while homeschooling her daughters.

“I love the country of the United States,” she said. “In my heart, I feel like it’s my country because I formed my girls as a U.S. citizen to love the country. But I am not able to be there.”

TPR was founded by and is supported by our community. If you value our commitment to the highest standards of responsible journalism and are able to do so, please consider making your gift of support today.