From KERA News:

The story of Dallas County’s health is, in many ways, a story of unequal distribution of chronic diseases. The last major health assessment of the county showed Parkland Health patients south of I-30 had a far higher count of cases of diabetes and hypertension than those north of the highway.

“The two chronic conditions that we focus on, that are paramount, are diabetes and hypertension,” said Jessica Hernandez, Vice President for Community Integrated Health at Parkland. It serves as the public health system for Dallas County.

Similar disparities existed for other ailments, like asthma, cancer, chronic heart failure, and chronic kidney disease.

So how was the community’s struggle with chronic disease affected by the pandemic, a time when health care workers were rushing to help people through a totally new disease? A new report for Dallas County that’s nearing completion may have those answers.

Community outreach

At the Marillac Community Center in West Dallas, you can dance at a birthday party and get a blood pressure reading on the same day.

Parkland Health has a weekly clinic in a quiet room. They take blood pressure readings and perform blood sugar tests for whoever wants one. Everyone is welcome — even walk-ins.

After his visit late last month, Arturo De La Sancha of Oak Cliff said he was surprised his glucose reading was high.

“Pues, no me siento mal. Yo no se porque. Estoy alterado de azucar pero no se por que,” De La Sancha said in Spanish. “Well, I don’t feel bad. My sugar is high, but I don’t know why.”

So now he needs to see a doctor to get to the bottom of it. That’s what the weekly clinic is for: giving people information and guidance about health issues they might not be aware of.

“Si no hubiera venido aquí, no me hubiera dar cuenta,” he said. “If I hadn’t come here, I wouldn’t have realized.” He said if he hadn’t come to the clinic, he wouldn’t have realized he needed to look into it.

Leonela Gonzalez, a senior community health worker at Parkland, said many patients mentioned that during the pandemic they were “not consistent with their blood pressure or their glucose because they were afraid to go see their doctor.”

The event at Marillac is an example of the kind of community outreach for chronic diseases that temporarily stopped in 2020, as fear of the pandemic took hold.

“It was months before our own internal infection prevention department and others would consider the possibility of us going out into the community in the way that we wanted to,” Hernandez said.

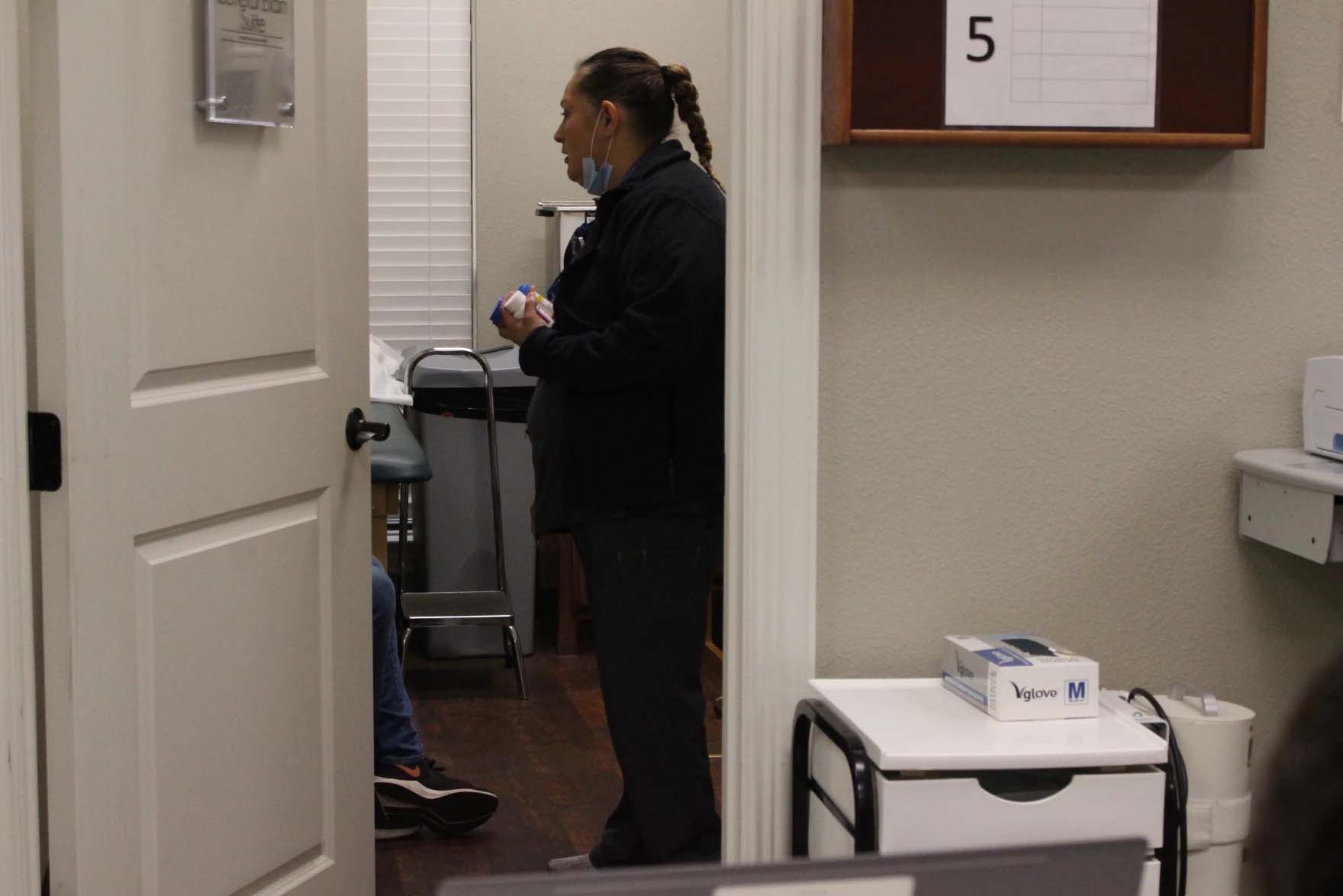

Leonela Gonzalez, a senior community health worker at Parkland Health, at a weekly clinic in West Dallas.

Bret Jaspers / KERA

Measuring progress

Hernandez said while these events were on pause — and staff scrambled to respond to the testing and treatment demands of COVID — the hospital refined how it would track and follow up with patients.

Outreach like this was part of the plan Parkland laid out to combat chronic diseases among its patients three years ago. That plan, called the Community Health Needs Assessment, is a requirement of the Affordable Care Act, passed by Congress over a decade ago. Tax-exempt organizations that operate hospitals must perform one every three years.

The 2022 Assessment is expected to be released this month.

In a presentation to its board, Parkland said it achieved some of the goals it set in 2019 for blood pressure and diabetes among its patients. But they failed to achieve others.

Parkland’s weekly clinic takes blood pressure and blood glucose readings.

Bret Jaspers / KERA

For example, Parkland surpassed its goal for the number of its patients in six targeted zip codes who received high blood pressure screenings over the past three fiscal years. During those same years, though, it didn’t hit targets for the percentage of patients with diabetes from those zip codes who had “adequately controlled” blood pressure.

Hernandez noted the metrics Parkland established were for their patients, not the county as a whole.

“That will come,” she said. She argued that three years is a very short time when you’re trying to improve the health of the community.

“I would love to see where we are ten years from now. Because really, it sometimes takes a generation to really see some of those improvements when you talk about population health,” she said.

And the responsibility to improve the county’s overall health also lies with private hospitals — mostly located in the Northern half of the county — and the state of Texas. The state is one of only twelve which haven’t expanded Medicaid.

“Medicaid expansion would put a quarter of a million of your neighbors here in Dallas County in coverage that currently don’t have it,” Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins said last week, noting that the “vast majority” of those uninsured people have jobs.

Dallas County has the highest uninsured rate of Texas’ largest six counties.

Primary care

Treating chronic disease takes consistent monitoring, like the screening De La Sancha had at the community center. And a primary care provider — be it a doctor or other medical professional — is key to that monitoring.

“If you’re taking care of your car, getting it maintained, taking care of your apartment and your home, you can take care of yourself,” said Joyce Tapley, CEO of the federally funded Foremost Family Health Clinics. “The best maintenance is going to a primary care doctor.”

At the Agape Clinic in Old East Dallas, which delivers primary care to people without insurance, medical assistant Guadalupe Delgadillo says the baseline health of her patients likely got worse during COVID-19.

“Because most of them, either they were too afraid to come here, or go to another clinic, or another place to get help due to the pandemic,” Delgadillo said. “They probably didn’t want to get COVID or something.”

Parkland, which serves a much higher percentage of the county’s uninsured at its hospital than all hospitals in the county, opened two primary care clinics in recent years, in the Red Bird area and Jubilee Park.

But nonprofit, community-based clinics like Foremost and Agape would like to see Parkland work with them more closely to connect people with primary care and reduce inefficiencies.

Paul Hoffman, executive director of the Agape Clinic. He would like Parkland Hospital specialists to take referrals directly from primary care providers at his clinic.

Bret Jaspers / KERA

Executive Director Paul Hoffman notes the majority of Agape’s patients live in the zip codes Parkland identified as having high percentages of chronic diseases. To improve how people get the care they need, he wants his doctors to be able to refer directly to Parkland specialists.

“What’ll happen is, they end up repeating all of the preliminary primary care work that we do before they even refer to a specialist,” he said.

And Tapley said she’d like to see Parkland refer people who come to the emergency room to her primary care clinic if they don’t really need to be in the ER.

“I have asked them as part of my contribution to the discussion that we formalize and be more consistent with how they’re referring patients to the most appropriate place,” she said.

Those ideas are on the table, Hernandez said, although they are working on how to communicate any care plan a specialist might devise for a patient back to that primary care doctor.

“Certainly, duplication is not what we’re after,” she said.