Audio will be available shortly.

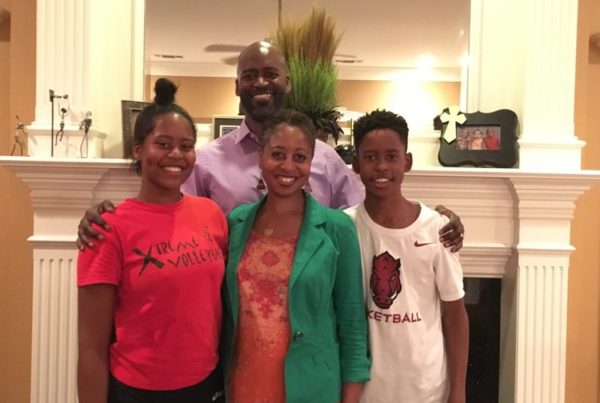

Sophomore David Molak was a student at Alamo Heights High School in San Antonio. He enjoyed fishing, was an Eagle Scout, a Spurs fan – in many ways, a typical high schooler.

Molak’s body was found in his backyard early this year, his death ruled as a suicide. In a news conference a few days later, his older brother revealed that David Molak had been mercilessly bullied by being piled upon with venomous texts, tweets and comments online. In David’s case, they mocked him and his intelligence, his looks, his girlfriend, posted doctored photos and threats. The cyberbullying had become so intense, his family had transferred David to another school. But the harassment continued.

A police investigation revealed the cyberbullying was real. But with schools potentially involved, privacy laws, difficulties connecting the dots between social media accounts and actual users, no one was held accountable in the end. Police said there was a lack of evidence.

Today in the Texas Capitol, a hearing will take place on what’s being called David’s Law – a proposal to try to stop cyberbullying. San Antonio state Sen. José Menéndez authored the bill. He says that David’s story, and a similar one – also in San Antonio – of a cancer patient being encouraged by cyberbullies to take his own life, are why he introduced the bill.

“This thing has snowballed through two very tragic situations here in San Antonio,” Menéndez says. “The Molak family has jumped in and they’re trying to make something positive out of the horrific tragedy their family has suffered.”

There are currently some cyberbullying laws on the books, but they don’t give much power to schools to do anything about it, Menéndez says. That’s what he’s hoping to change with David’s Law.

“It allows the school districts not to be able to say, ‘Well, it happened off campus, so we have no actual position or responsibility,'” Menéndez says. “I’m not trying to saddle the school districts, what I’m trying to say to them is that you need to be working hand in hand with the law enforcement community when there’s an investigation.”

The law goes a step further, too – it gives law enforcement subpoena power.

“[Police] can go to social media sites, and knock on someone’s door and say to a parent, ‘Do you know that an IP address at this address is being used to tell someone that they need to commit suicide … and they’re worthless and they should just kill themselves?'” Menéndez says.

He points to a similar law passed three years ago in Maryland – called Grace’s Law – to show that tougher laws on cyberbullying can hold up against challenges claiming that it oversteps First Amendment free speech protections.

“[Grace’s Law] actually talks about social media apps, and it found the needle, if you will, that we need to thread,” Menéndez says. “We have examples of another state that’s done this successfully, it’s held up, and we think we can do it here.”

Post by Alexandra Hart.