In the latest installment of our monthly series, “Texan Translation,” we examine the ways that English and Spanish combine to form what’s known as Spanglish.

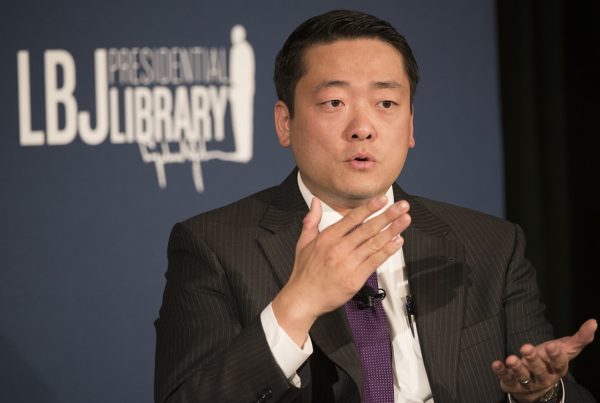

Lars Hinrichs, associate professor of English linguistics at the University of Texas at Austin, and director of the Texas English Project, says Spanglish isn’t as easy to define as it might seem.

“Spanglish obviously is some form of a mix of Spanish and English, but it’s different from other ways that languages can be mixed,” Hinrichs says. “It’s a special kind of linguistic practice that only exists in certain social spaces where there is a strong presence of the two cultures.”

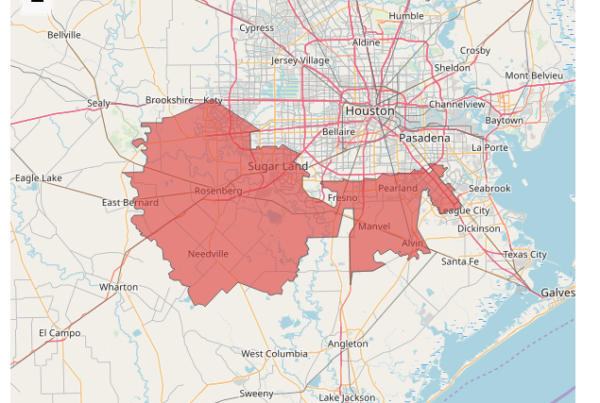

Spanglish thrives in areas like the Texas-Mexico border region, where English and Spanish are often used interchangeably by many bilingual speakers there.

Texas Standard reporter Joy Diaz, who speaks English, Spanish and Spanglish, agrees. She says Spanglish is even gaining recognition in the academic world.

“There’s even a class now at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio for Spanglish,” Diaz says.

For a practical application of Spanglish, Hinrichs and Diaz says it helps to look at a few common sentences and how they’re rendered in the three languages.

“Where’s your lunchbox?” is one example.

Diaz says that even when speaking Spanish alone, there’s the colloquial way, and the “purist way” of asking the common parental question.

In Spanglish, Diaz would say: “Dónde está tu lunchbox?”

Hinrichs says Spanglish is “the least formal, the most real mixing of the languages.” He notes the integration of the languages, but also the use of both pure English and pure Spanish in the Spanglish phrase.

In Spanglish, Diaz says “biles” means “to pay bills.” It’s not a Spanish word.

Hinrichs says “parquear” is Spanglish for “park a car,” and it’s an expression that’s only used in the Rio Grande Valley and other areas where Spanish and English coexist.

Some Spanish speakers aren’t fans of the blending and twisting of language.

“I know quite a few couples in Austin where one speaker is from the border region, a Spanglish speaker, and one person is from farther south in Mexico, or even Latin America. And they often have arguments about what proper Spanish is,” Hinrichs says.

Spanglish also utilizes what linguists call “false cognates” – words that look the same in both languages, and have the same meaning in Spanglish, but don’t actually mean the same thing in the standard version of the language.

“‘Librería’ in Spanglish can mean ‘library,’ but the actual Spanish meaning of librería is ‘bookstore,'” Hinrichs says.

Diaz says she’s “in love with Spanglish,” but realizes that many are not.

Hinrichs says that Spanglish is not so much a language as a linguistic “practice.”

“For Spanglish to become a language, it would need a governing class that speaks it,” Hinrichs says.

Listen to the full interview in the audio player above.

Written by Shelly Brisbin.