Horror stories of untested, long-forgotten and even moldy sexual assault evidence kits have been a problem in Texas for years. And those forgotten kits have been on Becky O’Neal’s mind for a long time.

“I can’t imagine that there’d be anything worse from knowing that your kit sat there and nobody ever cared enough about it to send it to see if there were any DNA hits on it or anything,” O’Neal says.

O’Neal has been a nurse and a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner – or SANE – for almost 30 years. She runs the team of SANE nurses in the Northwest Texas Healthcare System.

“If you have the courage to go through an exam, it’s nice to know that, that kit is not gonna sit there,” she says.

The mental image of a survivor’s traumatic experience being sealed away in a box, left to gather dust in a dark and damp evidence room, has continued to move many in the state to take action.

In a few months, the Texas Department of Public Safety will launch a new online portal that allows sexual assault survivors to monitor, in real time, the location of their evidence kit.

For Peter Stout, president and CEO of the Houston Forensic Science Center, the portal is long overdue.

“I find myself ranting a bit about how somehow in this country, we’ve managed to get a $20 pizza to somebody’s doorstep in 20 minutes, correctly,” he says. “It is infuriating that we can’t get evidence that affects somebody’s life to the lab reliably. I mean, these are the kind of systems that are necessary to get that stuff there.”

Last year, DPS bought the Track-Kit software from a Delaware-based company called STACS DNA. That purchase was made possible by legislation authored by Democratic state Rep. Donna Howard of Austin, which was made law two years ago. That law mandated that Texas have a statewide rape kit database.

Sonia Corrales, chief program officer and rape survivor advocate from the Houston Area Women’s Center, says adding better transparency and communication between survivors and law enforcement is needed.

“Typically, what was happening is that survivors tend to struggle to get information about their cases, and a lot of times they don’t really know how the evidence is being used,” Corrales says.

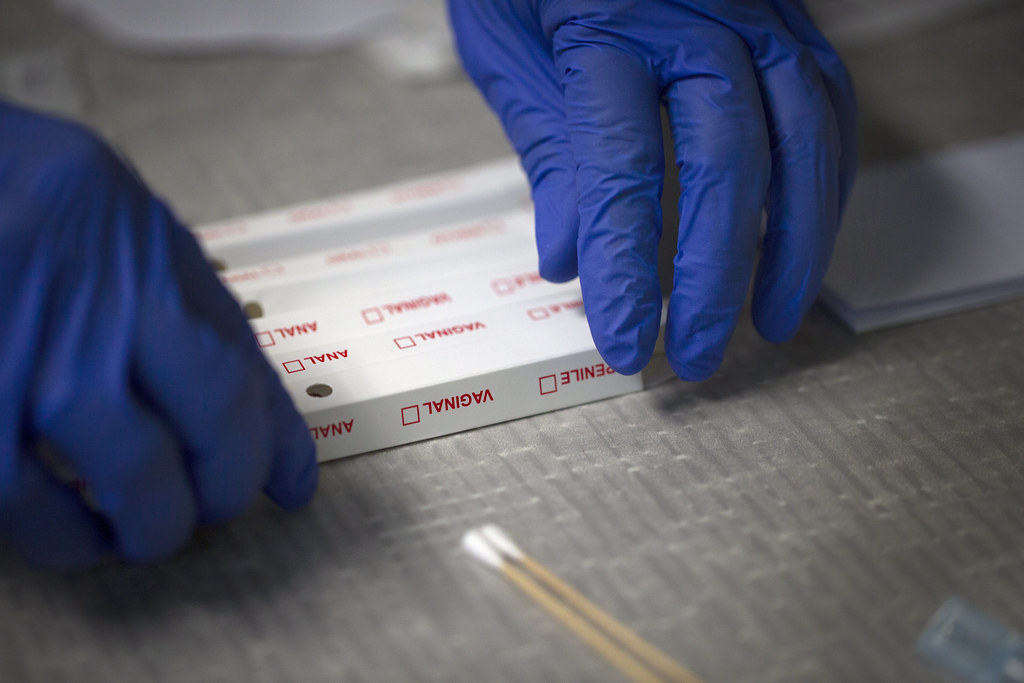

The process through which law enforcement collects that evidence can also be a traumatic experience for the survivors. These kits contain can contain a wide range of evidence samples from a survivor’s body, including saliva, semen, hair and clothing fibers. It’s all part of an effort to find anything that could identify an assailant. But after a sexual trauma, it can feel especially invasive.

O’Neal says in her experience, once a nurse sent a kit for testing, they were rarely, if ever, updated on its status.

“Before this tracking system, we had no idea what would happen to it. We were never informed it got sent. We were rarely informed that there was ever a DNA hit. We don’t have any contact again unless we end up in court with the victim at a trial date,” O’Neal says.

The new Track-Kit system is meant to address this issue. Through the online portal, it makes status updates on the kit accessible to all those working on the case – law enforcement, the nurse examiner, the laboratory and the prosecutor. But, most importantly to Lt. Ricardo Medina of the El Paso Police Department, it gives survivors peace of mind and allows them to remain anonymous.

“The victim has that reassurance that they’ll be able to enter the system and see where their sexual assault kit is,” Medina says. “They’ll know where it’s at, at what stage. That’s the huge difference here – it’s more for the victim, giving them that reassurance they need at times. To know the kit is moving forward and not just sitting somewhere. ”

There is one aspect of the new system, however, that concerns Corrales of the Houston Area Women’s Center.

“The password, for example,” she says. “I think that the forensic nurses are going to provide the password to them and how to get into the system.”

Immediately after entering the kit into Track-Kit, a nurse is supposed to hand the kit’s corresponding login card to the survivor. The card contains vital instructions for how to get onto the portal to monitor the kit.

“But when survivors are at the hospital, and there is evidence being collected from them because they are undergoing this forensic exam, they are in trauma, right? They’re experiencing trauma, so we weren’t sure how survivors were expected to remember that whole process,” Corrales says.

If a survivor loses their login credentials before being able to set up their account on Track-Kit, a law enforcement officer or forensic nurse will be able to provide them with new login information, according to DPS.

Corrales says, this is where community-based advocacy groups can step in to support the survivor at the hospital, and ensure they have all the information they need for the new system.

“It is important to get training on this process so that we are able to guide survivors through,” she says.

O’Neal says a nurse’s jobs isn’t just to collect evidence, but also to be there for the survivor.

“To be a sexual assault nurse, you have to be a very empathetic person. You have to sit with them, no matter how long it takes, and help them be able to express what has happened to them and feel safe doing that. You are seeing them at possibly one of their worst moments of their life,” O’Neal says.

The statewide launch of the Track-Kit program is scheduled for Sept. 1. But Lubbock, Amarillo, Arlington and Houston are part of an early launch now, and El Paso will start using the portal next week.

Medina of the El Paso Police Department says he’s not expecting any issues to come up during these early implementations. He’s also hopeful the program will close the communication gap between survivors and law enforcement.

“I think it’s a good idea, what we are doing,” he says. “I think it’s definitely a good idea the direction we are heading. I think it’s going to be helpful in the long run.”