From El Paso Matters:

This is the first in a two-part series on sexual harassment and gender discrimination within the El Paso Police Department. Read the second story here.

Editor’s note: This story contains graphic language and descriptions of sexual misconduct.

“I would walk by male officers and under their breath, they’d be like, ‘Fucking whore. Fucking bitch,’” an El Paso detective said, recalling her treatment after a male officer’s arrest for secretly filming their sexual encounter and sending the tape to other officers.

“Apparently, you’re a bitch for pressing charges,” she’d hear from friends who’d try to defend her to other officers. “You’re ruining his life.”

The El Paso Police Department is a hostile workplace for women, various current and former EPPD employees say, with a misogynistic work culture permissive of sexual harassment and sexism toward women officers and civilian employees alike.

In recent years, the department has been rocked by criminal cases of sexual misconduct: from the officer who made a sex tape of the detective without her consent; to another officer who allegedly sexually assaulted a teenager while off-duty; to still another officerwho reportedly tried to film his female co-workers changing in the women’s locker room after a family violence incident with his own wife.

In a seven-month investigation involving interviews with current and former EPPD employees, workplace diversity and policing experts and employment attorneys, as well as reviews of hundreds of pages of documents obtained through more than 40 public records requests, El Paso Matters found troubling information pointing to a police department unwilling to tackle gender discrimination within its ranks, and one where female employees may feel unwelcome to the point that they leave the department.

The El Paso Police Department Headquarters on Raynor Street. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Between 2010 and 2023, at least 10 EPPD officers have been arrested or indicted for sexual misconduct while on and off duty, according to an El Paso Matters review of news reports.

EPPD and the city of El Paso declined multiple interview requests from El Paso Matters, citing “ongoing investigations regarding this topic.” Asked to identify those investigations, they did not respond, nor did they respond to a detailed list of questions for this story. Officers named in various incident reports also did not return requests for comment.

El Paso Matters is not naming people targeted with alleged harassment or violence unless granted permission.

‘Everyone’s a victim’

The culture of gender discrimination goes beyond overt harassment within the ranks. It also can impact how El Paso police respond to violence against women, experts say – resulting in an insensitive, disbelieving or blaming attitude that affects how officers treat women in the community.

“In policing, I think it’s really important for people to be able to be on their toes and ready to roll at a moment’s notice,” said Mindy Bergman, a professor of organizational psychology at Texas A&M University who studies workplace diversity and policing. “But if you don’t trust the people you’re with and you’re looking out for who’s going to sexually harass you – it seems like a very bad thing for public safety and the safety of the police officer.”

Sgt. Rosalynn Carrasco, who retired from EPPD last summer after 20 years on the force, said “the reason there’s not more women in the department isn’t because they want to do less push-ups.”

“We know we have to hold our ground. We know we have to be physically in as good of shape as men; we understand that,” Carrasco said. “It’s when we’re ostracized for having the audacity to have a baby, for making waves or not knowing our place, that makes so many women leave the department.”

Carrasco, like virtually every woman officer interviewed for this story, stressed that she loved police work; it is the culture at EPPD that has long needed to change, she said.

“I really feel that everyone’s a victim, even the men and women that take part in this oppression of other women,” Carrasco said. “But until we have that conversation and acknowledge the problem, it’s never going to improve.”

The culture doesn’t just harm women, said a male officer who’s worked at EPPD for more than a decade and asked not to be identified to protect his career.

“The more that you listen to that garbage, the more you become that garbage,” he said. Watching officers go unpunished for harassing comments or behavior, and sometimes rise to supervisory positions in the department, offends his sense of fairness and justice – the very values that led him to policing, he said.

Invasive visual recording

It was her first day at work after months away. The detective sat in her car at the police headquarters parking lot in Central El Paso, still unsure if she’d go back in. There were so many reasons not to.

In the fall of 2020, a co-worker took her aside. “Don’t freak out,” the detective remembered hearing. “Somebody told me that supposedly there’s a sex tape of you.”

The co-worker was referring to a sexual encounter she’d had with Officer Irvin Mendez.

The detective, who asked that her name be withheld to protect her family from public scrutiny, met Mendez at the start of her career with EPPD. They carpooled to the El Paso Police Academy together, and four years later, were friends and co-workers at the Pebble Hills Regional Command Center in East El Paso.

In the early months of the pandemic, when Mendez thought he had COVID, it was the detective, he’d later say, who brought him medicine. They began dating in the spring of 2020 and slept together for the first time in June, a consensual encounter that didn’t happen again. They soon agreed to stop dating and stay friends.

“There was never a moment where I thought I couldn’t trust this person or that he had ill intentions,” said the detective, who was 30 at the time. “We had a close friendship, I thought.”

Mendez did not respond to El Paso Matters’ interview request.

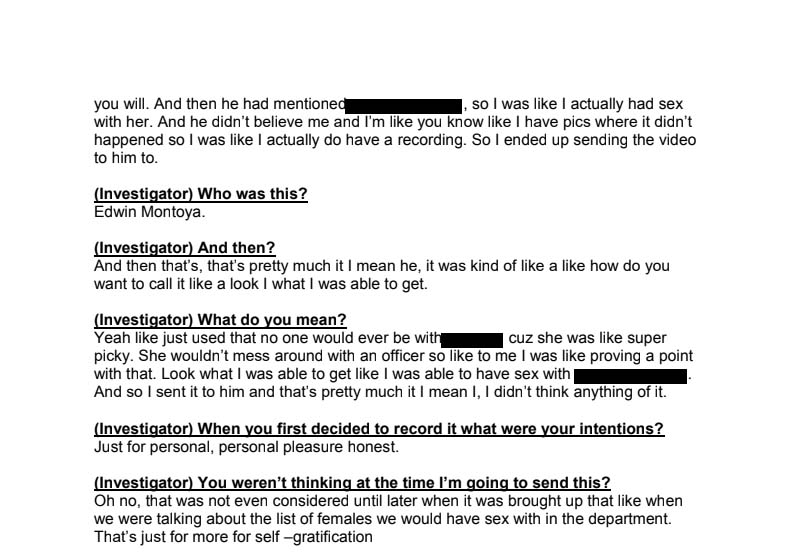

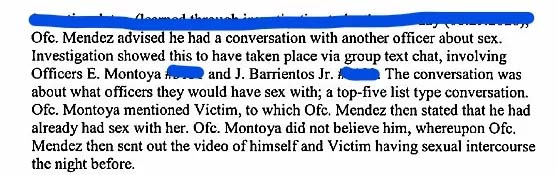

He secretly filmed the encounter, according to police and court records obtained through public information requests. The next day, he began texting with two on-duty officers, Edwin Montoya and Jose Barrientos, about the top five women officers they wanted to have sex with at EPPD. Mendez texted them the video.

By early November, according to Barrientos’ police statement, multiple Pebble Hills officers were talking about an explicit video of Mendez and the detective. One officer said Montoya showed him the video over lunch during an in-service training event on Nov. 18, with Barrientos sitting alongside.

Excerpt from former EPPD Officer Irvin Mendez to Internal Affairs investigators regarding him secretly taping a sexual encounter with a detective then sharing the video with other officers.

“I was like, proving a point with that,” Mendez said in a statement to police investigators, of his choice to share the video. “Look at what I was able to get.”

Hearing about the video, the detective began to cry. A friend asked her what was wrong. He suggested she submit a complaint with Internal Affairs, an administrative division within the police department that investigates employee misconduct allegations.

Mendez’s arrest and release on bond came within the week, on Nov. 25, 2020. Almost as swiftly, the detective said, the entire department seemed to know who she was – and that she’d asked to press charges – even though her identity was supposed to remain secret during the IA investigation.

She asked IA for the names of the officers who’d received and distributed the video because she wanted to file sexual harassment complaints against them. For months, IA said they couldn’t tell her until the case was complete. “I spent the majority of that time basically in purgatory. Who in this department has seen me naked?” she wondered.

Excerpt from an EPPD Internal Affairs summary report on former Officer Irvin Mendez secretly filming a sexual encounter with a female detective and texting the video to other officers.

Her mental health spiraled; soon, she dropped 15 pounds. Though she reported the harassing comments she’d hear, she was told she needed more proof. “I would go home and cry and my kids would see me cry. It was horrible because I wasn’t there for them as a mother,” she recalled. After five months, she said supervisors finally placed gag orders on Pebble Hills officers, barring them from discussing her case. “My life was just falling apart. And the department was doing nothing to help me.”

Nearly three years have passed.

Mendez, the officer who filmed her, was allowed to resign instead of getting fired. Although he pleaded guilty last August to invasive visual recording, a state jail felony, he will be allowed to apply for judicial clemency. If granted, clemency could allow him to expunge his record and return to law enforcement.

Montoya, the officer who showed others the video, was also allowed to resign instead of being fired. Montoya could not be reached for comment.

Barrientos remains in the department. In May 2021, a Special Discipline Review Board voted to give him 30 days’ aggravated suspension – the maximum suspension possible for an officer. The board noted that Barrientos had not come forward to report knowledge of a possible crime, even after Mendez was arrested. The late EPPD Chief Greg Allen slashed his suspension hours by a third as part of a settlement agreement.

Now, Barrientos is up for promotion to sergeant.

The detective, meanwhile, is still hanging on. After months of runaway gossip, she gave in to a supervisor’s suggestion that she transfer stations. But the harassing comments and discrimination followed her there, she said, and continue to this day.

The same day as Mendez’s arrest, police records show the detective was placed in a mandatory stress management program. Under the terms of the program, she’d receive no overtime credit for the hours spent in counseling, and could be disciplined for non-compliance. On at least one occasion, she was threatened with discipline for missing sessions, according to documents reviewed by El Paso Matters.

In contrast, per EPPD records, none of the officers disciplined in the case were required to undergo counseling or sexual harassment training.

Now seven years on the force, the detective said sexism at the department hasn’t improved – if anything, it’s getting worse, she said. “It’s almost like you’re just trying to survive your career for as long as you can.”

The importance of women officers

Police departments need women officers. A number of studies have found they’re less likely to use excessive force against civilians.

“The research shows that police agencies that have a higher representation of police women have better outcomes for crime victims, specifically for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault,” said Ivonne Roman, a former police chief and co-founder of the 30×30 Initiative, which aims to increase the number of women in policing. “You’ll have better outcomes, you’ll have more reporting, and there’ll be better quality of service that those crime victims receive.”

Despite the strong evidence that women officers improve public safety, U.S. police departments have far fewer women than other industrialized nations. Countries like Australia, the United Kingdom and South Africa have nearly double the proportion of women officers typical of a U.S. police department, including El Paso.

The El Paso Police Department Headquarters on Raynor Street. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

And while the number of female officers in El Paso has increased over the years, between 2010 and 2022, women officers were 33% more likely to resign from the department than men, an El Paso Matters analysis of EPPD data found. In that time, an average of 12% of El Paso police officers were female – but nearly 16% of resignations have been by women.

In August, a department spokesperson told El Paso Matters that EPPD has no policies in place to improve retention of women officers.

Roman cautioned that it’s not enough simply to recruit more women to policing. Departments must also tackle what she describes as a hypermasculine police culture. “We don’t want women coming en masse to an environment that wouldn’t be supportive. We want women to actually thrive – not just survive.”

What counts as sexual harassment?

The city of El Paso and the police department have a “zero tolerance” policy toward sexual harassment. Under EPPD’s policy and procedures manual, “sexual harassment is viewed by the department as serious misconduct that may result in disciplinary action as serious as termination.”

Since 2010, there have been 34 employee complaints “with regard to sexual harassment,” EPPD said in response to a public records request – a number many sources say far understates the extent of sexual harassment within the department.

The city has withheld most of these complaint records, arguing that in Texas, police misconduct investigations are considered confidential unless an officer was disciplined. Even then, that discipline would have to take the form of removal, suspension, demotion or uncompensated duty before a misconduct investigation is open to the public, making it difficult to evaluate police departments’ handling of internal investigations.

Greg Allen served as El Paso police chief from 2008 until his death in January 2023.

For example, EPPD records show that Allen was accused of sexual harassment and “screened” by Internal Affairs in 2012 when he was chief of police. The action taken in his case is described as “training” and the city has denied El Paso Matters’ request for additional information about the allegations or how the case was handled.

In addition to declining an interview and declining to answer written questions about its policies, the police department has on multiple occasions provided incomplete or inaccurate responses to public records requests, and often failed to produce requested records in timeframes required by the Texas Public Information Act. In one instance, the city ignored an order from the Texas Attorney General’s Office to produce case records.

The police department does not appear to systematically track or clearly record instances of sexual harassment, often classifying these violations in broad terms that obscure the nature of officers’ actions.

In the detective’s invasive visual recording case, for example, though each of the three officers was disciplined for sexual harassment, you wouldn’t know it from their disciplinary history cards.

The settlement agreement for Barrientos, who still works at EPPD, stipulates that this discipline history card would reflect his suspension for violating “Rule 4 Dereliction of Duty, Rule 11 Gossiping, Rule 27 Adherence to law enforcement code of ethics, Sexual Harassment.”

Each of these violations appear word for word on the card, a document supervisors rely on when making internal hiring decisions. The only two words missing are “sexual harassment.”

This practice appears to have precedent.

Joe Molinar, District 4 City Council representative, attends a meeting on March 13. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

In 2000, El Paso city Rep. Joe Molinar, then a lieutenant at the Northeast Regional Command Center, was disciplined for violating the department’s sexual harassment policy. He received a written reprimand and mandatory sexual harassment training, according to records obtained through a public information request.

But on his disciplinary history card, sections listing the case allegations and disposition failed to mention sexual harassment. All that appears is that he’d received a “written reprimand” for “unprofessional conduct – other.” Molinar was recently admonished by City Council for allegedly sexually harassing a city employee last fall.

Besides the detective’s invasive visual recording case – where she said she pushed hard to add sexual harassment as a violation – it has been nearly a decade since EPPD disciplined an officer for sexual harassment, according to its responses to public records requests. Since 2010, just four sexual harassment investigations have resulted in officer discipline.

However, case files provided to El Paso Matters by sources reveal an investigative system that treats harassing or sexually inappropriate behavior less seriously than other employee violations – including when it comes to behavior by people in powerful or supervisory positions at the department.

In May 2020, a group of police officers in the report room at the Northeast Regional Command Center were discussing a citizen complaint against Officer Danny Conway for alleged sexual harassment, according to police documents reviewed by El Paso Matters.

The El Paso Police Department Northeast Regional Command on Dyer Street. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

A new officer spoke up and said she wouldn’t be surprised if it were true. Something similar had happened to her just a month earlier.

Just graduated from the police academy with roughly eight months on the force, the new officer had been rotating through different units as part of a yearlong period of “probation” before becoming a fully-sworn police officer. It was her first day working under Conway, who as her field training officer held sway over whether she could stay on the force: A bad performance evaluation by him could keep her from joining the department at all.

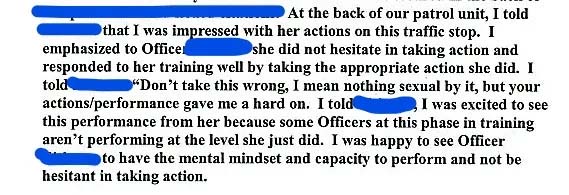

In April 2020, they’d just finished responding to a traffic violation together. They were waiting for a tow truck to arrive when Conway began “looking up and down my body,” the new officer later said in a statement to police investigators. “Officer Conway then asked if my mic was on, referring to the microphone that is connected to the camera of the patrol unit.” She told him it wasn’t. “Then he said ‘that gave me a hard-on.’”

Excerpt from EPPD Officer Danny Conway’s statement to Internal Affairs investigators regarding lewd comments he made to a female officer after a traffic stop in 2020.

The new officer didn’t report Conway’s comment. But after hearing her account in the report room, another female officer decided to tell a supervisor. “The situation had been bothering me,” the complainant officer said in her statement to Internal Affairs investigators. When she started at EPPD, coworkers had warned her to “be careful” around Conway because he was known for making “inappropriate comments to female officers,” she told investigators.

The new officer said she took Conway’s comment to mean that “my performance at the traffic stop gave him some sort of sexual gratification,” she said in her statement. Though she felt “confused,” “uncomfortable,” and “shocked,” she told investigators that it was a one-time incident and that she didn’t feel sexually harassed or threatened.

Conway acknowledged saying this to his trainee, but said she’d taken it wrong: He’d meant to convey that he was “impressed” by her “mental mindset and capacity” during the traffic call and didn’t mean anything sexual by it, according to his statement to investigators.

Internal Affairs investigators presented the case to the EPPD Discipline Review Board on Sept. 9, 2020. The board is made up of six members of the police department, a representative from the department’s human resources department, and six community members whose applications to serve on the board are screened and approved by EPPD.

The review board doesn’t receive information about an officer’s past actions or history when deciding whether to sustain a misconduct allegation. The board does take this information into account when deciding how much discipline to issue, however; it can also consider “whether the employee is in a supervisory or management role,” EPPD’s policy and procedure manual says. “It is the Department’s intent that individuals in a supervisory or management role will be held to a higher standard with regard to their conduct.”

For improper use of a microphone and for Conway’s comments to his trainee, the DRB gave him a day’s suspension. In a settlement agreement, Allen reduced Conway’s discipline to five hours.

The DRB classified Conway’s comment as a violation of Rule 9, Conduct Discrediting to the Department – which includes behavior that creates an “intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.”

It did not classify the incident as involving sexual harassment.

Disparity in Discipline

After 20 years at EPPD, former Sgt. Linda Hanner has noticed patterns in how the department disciplines its own: it plays favorites, “picking and choosing” who to punish and who to let off, she said.

The Internal Affairs division is just that – internal. It’s staffed by officers and overseen by the chief of police. In contrast to cities like Dallas, Austin and Fort Worth, El Paso has no independent police oversight body.

Hanner loved police work, and retired in 2022 after more than two decades on the force. But that retirement came earlier than she’d wanted. Her health gave out, something she attributes in part to stress caused by a 2019 complaint she brought against her supervisor at the Mission Valley Regional Command Center that went nowhere.

“I’m just really sad,” she said, her voice breaking. “I decided it was better to leave than to stay and fight and find my way back to what I love to do. … And I’m not the only one.”

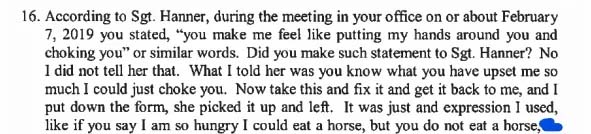

Hanner accused Lt. James Lockhart of belittling her at team meetings, repeatedly threatening to transfer her or call Allen to get her demoted, and during a heated one-on-one meeting, of saying “sometimes you make me feel like putting my hands around your neck and chok(ing) the fuck out of you,” according to her complaint.

Excerpt from EPPD Lt. James Lockhart’s statement to Internal Affairs investigators on a 2019 complaint brought against him by then-Sgt. Linda Hanner.

When the DRB voted to not sustain any of Hanner’s allegations against Lockhart, she assumed that the board simply hadn’t believed her word against his. After all, when a police commander initially asked Lockhart about saying he wanted to choke Hanner, he denied it.

But when Hanner received the full case file through a public records request she submitted, she learned that some officers said they’d witnessed Lockhart belittling her. And in a reversal of his earlier denial to the commander, Lockhart acknowledged telling Hanner, in his words, “you have upset me so much I could just choke you.”

“It was just an expression I used, like if you say I am so hungry I could eat a horse, but you do not eat a horse,” Lockhart said to investigators, later adding that she had a “sad look on her face like her feelings were hurt.”

These outcomes are even more galling to Hanner given the discipline she’d received in 2018. Hanner reported herself for flipping off a female lieutenant behind her back, as other officers looked on.

For this, Hanner received two days’ suspension from the DRB, which also mandated that she submit a written apology to the lieutenant. In a settlement agreement, Allen reduced Hanner’s discipline from 16 to 11 suspension hours, more than double Conway’s punishment for the lewd comment to his trainee and improper use of a microphone. The DRB also classified Hanner’s behavior as Class C violation compared to Conway’s comment to his trainee, which was listed as a less serious Class B offense.

Carlos Ramirez, the head of EPPD’s Human Resources Department, was among those whose votes cast Conway’s conduct as a less serious violation than Hanner’s.

Hanner said she deserved to be held accountable for her actions. But what still stings, she said, is “the disparity – and the hypocrisy.”

‘A failure of leadership’

Some harassing incidents don’t make it to a review board at all.

In September 2021, Sgt. Daniel Davis and seven other officers responded to a family violence call, according to police records reviewed by El Paso Matters. A man had allegedly attempted to choke a woman and was wielding a gun, but the officers managed to arrest him.

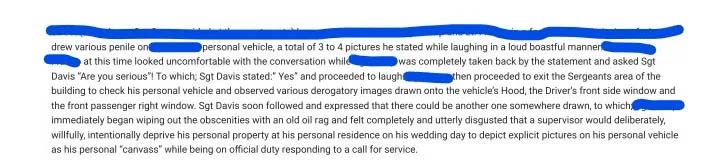

As they were leaving the scene, Davis noticed a red truck parked nearby belonging to another male sergeant who happened to live in the same apartment complex.

Davis “proceeded to draw with his finger a derogative picture of a ‘penis’ on the hood of the truck, and the Driver’s side window of the truck,” according to a complaint submitted by the other sergeant. Davis did so in front of “an impressionable young Officer” with less than three years in the department, the sergeant noted, adding that Davis was well aware it was also the sergeant’s wedding day. But most concerning, the sergeant noted, was that Davis was on duty and supervising other officers responding to a high-priority call.

The sergeant later learned that Davis’ drawings had been the “highlight of discussion” in the report room of the Northeast Regional Command Center. “This not only undermined my authority as a graveyard supervisor but created a humiliating experience,” the sergeant wrote, “that showed a blatant disrespect.”

Excerpt from an EPPD sergeant’s complaint regarding the behavior of Sgt. Daniel Davis after a 2021 family violence call.

In his complaint, the sergeant said he’d “thought long and hard to write this documentation against a fellow supervisor.” He decided to do so, he wrote, because he believed officers should be held accountable for their conduct.

Five days later, Lt. Frank Rodriguez Jr. encouraged the sergeant to drop the complaint.

“Having worked with Sgt. Davis in the past, I have known him to pull pranks like these but never in a malicious manner,” Rodriguez wrote. “In fact, he only does this with people that he likes. I believe this to be a misunderstanding that should have resulted in a discussion instead of an investigation. Recommend filing/no further investigation.”

A week later, records show, the sergeant withdrew the complaint.

Mindy Bergman

Bergman, the Texas A&M professor of organizational psychology, discussed these cases with El Paso Matters, and described them as important in establishing workplace norms.

Take the “impressionable young Officer” noted in the sergeant’s report: “Now this new recruit thinks this is good behavior – or not good behavior, but tolerated behavior, or what leaders do in this organization,” she said. “And then when that person doesn’t get punished, the new recruit thinks, ‘Oh, to become a leader, or popular in this policing organization, this is what I need to do.’ That’s how it gets perpetuated.”

Nor should Davis’ actions, or the comments made by Lockhart or Conway, be written off as “blowing off steam,” she said. “These are people who are engaging in essentially power plays disguised as blowing off steam. Blowing off steam productively doesn’t look like this.”

She sees a clear connection between these incidents and the sex crimes committed against the detective and possibly other women in the department.

“This climate is functioning so that people think they can get away with egregious interpersonal behavior, especially when it has a sexual component to it,” Bergman said.

Taken together, the incidents point to a “failure of leadership” at the El Paso Police Department, Bergman said.

“The leadership decides disciplinary action. Either they’re unaware, which is a failure of leadership, because they should know what’s happening,” she said. “Or they don’t care, which is a failure of leadership – because they should care.”

Attitudes spill over to treatment of public

Police leadership needs to tackle “subtle as well as overt” forms of discrimination in their departments, says a 2011 report on sexual misconduct in law enforcement published by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. “The potential for these attitudes to spill over and affect the perception and treatment of members of the public should also be recognized and addressed.”

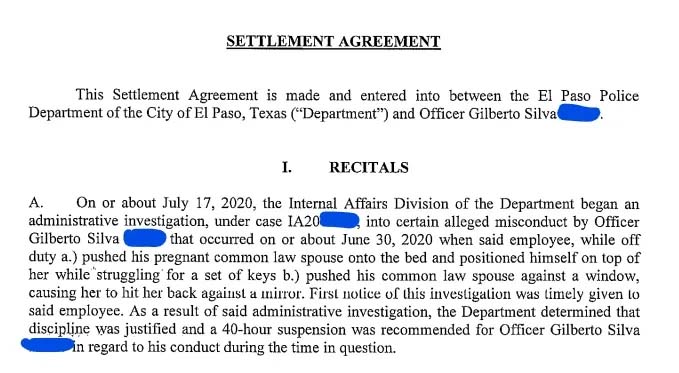

In December 2022, El Paso Officer Gilberto Silva was arrested for allegedly filming inside the women’s locker room of the Westside Regional Command Center.

Well before a female officer reportedly came upon him attempting to film his co-workers in April 2022, Silva’s common-law wife warned the department of his problematic behavior: It had been directed at her first. Two years earlier, in June 2020, she’d called 911 on him for family violence.

She submitted a statement to Internal Affairs in December 2020 critical of how police had treated her call. The responding officers had initially been sympathetic, she wrote, but when “they found out Gilbert was an officer, they called the supervisor.”

The supervisor began questioning her a second time, asking if she was “sure that’s what happened,” she said. “The supervisor kept doubting me which made me feel like he was defending Gilbert since he was an officer.”

Then, someone even higher up arrived at the scene – possibly a commander, she said – and began questioning her again. “The commander kept telling me he wanted to talk to me to make sure I was consistent with my story,” she said. The officers’ report stated she hadn’t been consistent.

The first officers to the scene noted that Silva had no injuries; his wife, who was five months pregnant, was bruised on her arms and back with a red scratch across her chest. Strands of her hair were found stuck in the window blinds, where she said Silva had pushed her during their argument.

But because each accused the other of behaving violently, and because there were no witnesses – save the couple’s 3-year-old daughter, who was in the room – responding officers said they chose not to arrest Silva or present the incident to the District Attorney’s Office for screening. Commander Juan Briones in his statement to IA investigators described what had happened as a “family fight.”

Though EPPD opened an Internal Affairs and possible criminal investigation into Silva’s actions a few weeks after the incident, nearly two years passed before he was disciplined, receiving three and a half days’ suspension as part of his settlement agreement. He remained on active duty for 10 months – even after his wife’s December 2020 statement that “in the past, he has threatened to do things to me with his weapons.”

“If there was something he didn’t like that I said, he would be holding his gun in his hand waving it around, and say things like ‘what’d you say?’” she wrote.

Silva was indicted on March 10, 2021, for assault of a pregnant person – charges that were later dismissed at the request of the complaining witness. On April 23, 2021, EPPD put Silva on paid administrative leave for the incident. He wasn’t supposed to enter police buildings, according to the terms of his leave obtained through public records requests. He was taken off leave nearly a year later, in late March 2022, EPPD said in response to public records requests.

Five weeks after Silva returned to policing, a female officer allegedly found him in the women’s locker room, according to an incident report. He was trying to tape his cell phone inside a locker, to face the women’s changing area. A search of his phone revealed 15 video recordings inside the women’s locker room filmed between April 28 and April 30, 2022, as well as five photos of women’s undergarments, taken in what appears to be the locker room, on April 18 of that same year. EPPD placed Silva on paid leave for one day following this incident.

It wasn’t until he was arrested and released on bond from the El Paso County Jail on Dec. 15, 2022, that Silva was put on leave again, this time for six weeks – receiving nearly $81,000 for his periods of paid leave, according to EPPD. He now faces several charges, including attempted invasive visual recording and indecency with a child by exposure.

“We have police officers engaging in sexual voyeurism amongst the police department, in addition to someone committing domestic violence, which is usually a sign that they need to be nowhere near a gun,” Bergman said. “They’re not just harming the policing organization and they’re not just breaking the law; they’re doing both at once. They’re undermining the women in their workplace. They’re undermining the functioning of the police department.”

It matters who shows up

Long before she joined EPPD, the detective who was videotaped had been terrified of police. Growing up in El Paso, her parents fought often, in arguments fueled by her father’s alcoholism, she said. On at least two occasions, officers arrested both parents.

Then, when she was in high school, an EPPD officer arrived who listened to her. “Just to have an adult, and especially an adult in uniform, say, ‘Hey, it’s going to be OK’ – that was huge for me,” the detective recalled.

The experience taught her it matters who shows up.

Officers’ views of women can affect how they approach policing, she said, including how they treat female crime victims and how they treat crimes like sexual assault and family violence.

“The go-to thing to say is, ‘Was it real sexual assault, though? Or is she just trying to get back at the guy?’” the detective said. “They don’t even care if it’s in front of a female because it’s like, if we complain, then we’re outcasted. If we complain, then we’re shunned.”

She described those types of comments as “common” for the report room.

“If they can say those things and treat me the way they have, how are they with complete strangers?” she asked. “It’s terrifying to think if something happens to my daughter, what type of person is going to respond? Are they going to take it seriously? Or are they going to just do this shitty report because they think she’s lying because that’s their mentality – in their heads, they’re thinking she must have wanted it. And that’s terrifying.”

Gender bias and public safety

Two out of three sexual assaults go unreported to police, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, a national anti-sexual violence organization; 13% of people who don’t report say it’s because they believe police won’t help them.

Ydali Phoenix-Cervantes became a victim services case manager at EPPD because she wanted to help change policing. Before joining the police department, she’d worked at El Paso’s Center Against Sexual and Family Violence, where she provided hospital accompaniment to people who’d been sexually assaulted.

She’d often wait outside hospital rooms with police officers as women were being examined or treated for sexual assault. Many displayed an insensitivity toward sexual violence, she said.

“They’re just joking away, making fun of things or making inappropriate comments – sometimes about females. It made me so mad because I’d tell them: ‘This person is listening. She’s listening to you. She can hear you laughing, joking, saying all these things,’” Phoenix-Cervantes said.

When she joined the department, she hoped to help train officers to better interact with victims. What she found was a more deeply entrenched attitude than she’d been expecting – stemming from department leadership.

In May 2021, the department announced the arrest of EPPD Officer Abderrazak Boukhatmi, who allegedly forced a 19-year-old girl to perform oral sex while working off-duty as a “courtesy officer” at her apartment complex.

In response to EPPD’s press release, Lt. Marshal DeMunbrun emailed the entire department: “We’ve heard the term victimization – people placing themselves in positions to become victims. As officers, we have to make sure we are not placing ourselves in positions to be accused!” he wrote in emails obtained by El Paso Matters through public records requests.

Phoenix-Cervantes was floored by the lieutenant’s response – and very angry, she recalled. Still, she hesitated before writing him back; hierarchy mattered at the department. Here was a top-ranking lieutenant, “and I’m just a little peon,” she said.

She decided to send DeMunbrun a private email. “With all due respect Sir, I disagree with some of your comments. The term victimization refers to the deliberate action or process taken by someone to exploit, oppress, or harm another. What you described is Blaming the Victim, which (is) a very common belief based in deeply rooted societal attitudes towards gender inequality.”

“I think you misinterpreted the point I was trying to convey,” DeMunbrun wrote back. “Let me explain the context of the term victimization – when people partake in actions or behavior that increase the risk of becoming a victim of a crime. For example, a person walking through a dark alley of a high crime area, alone. Chances are increased they could be victimized.”

Phoenix-Cervantes left EPPD when she moved out of state. In her September 2022 exit interview, she noted that there was a “good ol’ boys mentality” that she did not believe would improve without a wide-ranging change in leadership.

As it begins its search for a new police chief following Allen’s death in January, the city has the chance to select a candidate capable of reforming this culture, said Sgt. Carrasco, who was also disturbed by DeMunbrun’s email.

She waited a few days and then replied to it in an email that went out to the entire department: “I was hoping this email would be addressed to (the police department listserv) by a rank much higher than my own,” she began. “The word victimization had no place being in this e-mail. A rape victim does not place herself in a situation to become a victim. … Not raping someone is not a sacrifice a good officer must make nor should one be reminded that not raping someone is doing what’s right.”

She quickly received a text to her cell phone from her commander: “Authority Chief Allen, do not comment any further on criminal cases over email.”

She wrote back. “Duly noted, sir.”