From El Paso Matters:

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part investigative series on sexual harassment and gender discrimination within the El Paso Police Department. Read the first story here.

The officers cast the need for reform in stark terms: “As an employee of the police department I would never want my own daughter to work among some of the men within this department.”

That’s how the proposal to form an El Paso Police Women’s and LGBT Equality Committee reads. It was submitted by three female officers to El Paso Police Department leadership in April 2022.

“(G)enuine, systemic equality for women within our Department and within our union is still vastly unrecognized and devalued,” the proposal reads, stating that despite the “many wonderful men within the department who advocate for equality and disdain the violence against women,” the work environment for women remained “toxic.”

The committee would be open to all ranks and genders to create a “dialogue between female, male, and LGBT officers,” according to the proposal. It would aim to tackle a range of problems within the department – from sexual harassment and EPPD’s lack of paid parental leave, to limited breast pumping accommodations for new parents. It also included community outreach goals: the committee would work to inform El Paso women, young girls and members of the LGBTQ community of their rights.

The four-page proposal was signed by Sgt. Rosalynn “Roz” Carrasco and two detectives, including one whose choice to report a male officer for sexual misconduct against her sparked backlash that nearly drove her from policing.

Carrasco spearheaded the proposal, but said the committee wasn’t her idea; a supervisor, Assistant Chief Humberto Talamantes, had first suggested it. “This is something I have hoped for a long time and am grateful the support is finally here,” she wrote in an email to the detectives, obtained by El Paso Matters through records requests.

But the support, it turned out, wasn’t there – not even from the man who’d suggested it, according to Carrasco.

Though she and others have for years sought to improve gender equality at EPPD, they say many of their efforts have been met with setbacks, departmental inaction, and in some cases, retaliation.

Carrasco, along with the detective and other current and former EPPD staff, began speaking to El Paso Matters about the police department’s treatment of women employees following a fall article about two EPPD officers who are sisters. “Not all women are received so kindly,” retired Sgt. Linda Hanner wrote in a September 2022 email to the news organization. “Some of us battled it out for 20 years.”

El Paso Matters began investigating the women’s concerns months before the death of El Paso Police Chief Greg Allen in January and the subsequent appointment of Interim Chief Peter Pacillas.

The city and the Police Department have declined multiple interview requests, citing “ongoing investigations regarding this topic,” and did not respond to detailed written questions.

With the city’s search for a new police chief now underway, many hope for a candidatewilling to tackle sexism and other cultural and systemic problems within the department.

‘Not fair to male officers’

After submitting the proposal, Carrasco and the detective, who asked that her name be withheld to protect her family from public scrutiny, met with Talamantes and Commander Juan Briones to discuss the committee’s formation.

That meeting didn’t go as planned, Carrasco recalled. “They said, ‘Well, thank you, Roz. We dealt with some of your complaints.’” They showed them the newly painted lactation room at police headquarters and said they’d be ordering “Sally Brown” gun belts for women officers – designed to fit women’s bodies, in contrast to “Sam Brown” belts designed for men.

But new gun belts and a coat of paint were far too little to address wide-ranging systemic problems in the department, Carrasco felt.

She asked about the women’s committee. “They go, ‘You know, we’ve decided – Allen has decided – that it’s not fair to male officers,’” Carrasco recalled. A women’s committee would be “exclusive” and “divisive,” both Carrasco and the detective remembered hearing.

The supervisors knew Carrasco was planning to retire in a few months. She said Talamantes asked her, “What can we do to keep you here?”

“This,” she replied – greenlight the women’s committee. “Do this and I’ll stay.”

“They just brushed it aside like I didn’t even say it,” Carrasco recalled. She retired from the force last August.

Retaliation in many forms

“If you could change anything about your experience of working with the City of El Paso, what would you change?” reads an exit interview question for departing employees.

“I wish I had fought the sexism that I encountered,” wrote Jessica Miller, a police toxicologist, in April 2022.

But those who do fight sexism in the department can face blowback, Carrasco said. “Women are put in these situations where either you turn your back and you stay silent,” she said, or you speak up “and you suffer the consequences.”

Retaliation at EPPD can be subtle – and “intricate,” said El Paso employment law attorney John Wenke. “There’s still very much that environment where, if you complain, there’s no question you will get retaliated against — in the form of transfers, in the form of discipline, in the form of Internal Affairs complaints,” he said.

Carrasco spent about three years in EPPD’s Internal Affairs division, which investigates employee misconduct allegations, and echoed Wenke’s observations.

“I saw this from the inside out,” she said. “These people that would come forward with sexual harassment or discrimination allegations, they would always end up an accused, and they would always be punished for something separate. Was it ever said this was a result of their coming forward? No.”

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission allows workers to submit discrimination charges against their employers based on nine different categories – among them, race, age, disability, retaliation and sex. Many of these categories, including sex, are protected by Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

El Paso Police Department headquarters at 911 N. Raynor St. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Since 2010, about 40% of the EEOC complaints filed by EPPD employees have come from women alleging sex discrimination, according to records obtained by El Paso Matters through public information requests. Three of every four sex discrimination charges also included allegations of retaliation for filing internal sexual harassment or gender discrimination complaints within the police department, or as a result of filing an earlier EEOC charge.

One former officer who’d worked nearly 20 years at the department said in her EEOC complaint that she was given a “fitness for duty evaluation” and relieved of duty in 2014 after reporting sexually harassing texts and comments from her supervisor. She is suing the city and a trial in her case is scheduled for September, according to court documents.

El Paso Matters is not naming alleged targets of harassment or discrimination without receiving their permission to do so.

In a 2022 EEOC complaint, another longtime officer said an Internal Affairs investigation was opened against her after she complained that two male supervisors had created a hostile work environment for women in her unit. She said she was then made to transfer stations and placed on a graveyard shift.

Male officers who’ve attempted to support their female co-workers may also experience retaliation, according to EEOC and court records. In a 2015 EEOC complaint, an EPPD lieutenant said he was demoted and forced to retire after he tried to stop ongoing sexual harassment and discrimination against a female officer who’d filed a series of complaints that went nowhere.

“I have been moved to a different location which is far from my home and now I am (being) subjected to false accusations and to an internal investigation,” the lieutenant wrote in his second of three EEOC retaliation complaints, “when all I did is protect and stand up against wrong doing, discrimination, hostile work environment and retaliation.” He and the female officer sued the city and reached a settlement agreement in 2022, court records show.

On May 19, the detective filed her own EEOC complaint alleging sex discrimination and retaliation. The complaint didn’t center on the sexual misconduct committed against her by a male officer in June 2020, or the backlash she later experienced for reporting him. In Texas, workers have 300 days after an incident to file a complaint through the EEOC.

But since then, the detective said she’s continued to experience gender discrimination and retaliation, including through an Internal Affairs case against her involving alleged time card violations, which she’s in the process of appealing.

History repeats itself

The three officers’ push for an equality committee was informed by history. Years earlier, an EPPD women’s committee had served as an important vehicle for departmental reform.

Teresa M. Chavira joined EPPD in 1988 – a time when gender dynamics in the department were especially fraught. The resistance to women in policing came as a surprise to Chavira, who was raised by parents who modeled equality. Her father, a firefighter, “expected me to be strong,” Chavira recalled. He’d help cook and clean while her mother studied to earn a Ph.D.

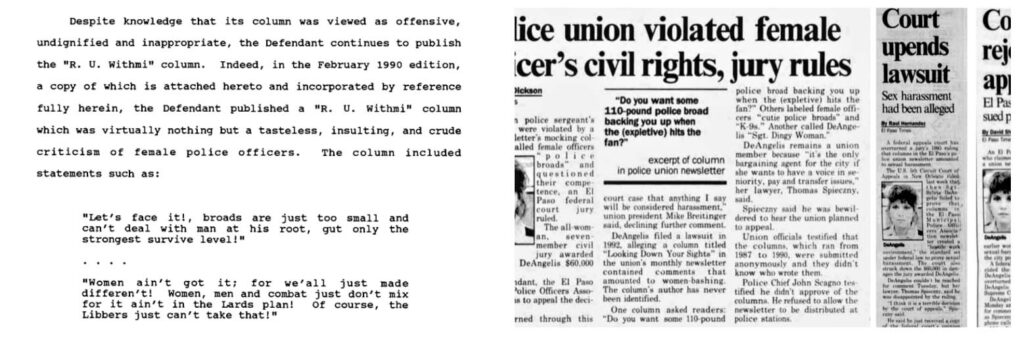

Columns like this one in the El Paso Municipal Police Officers Association’s newsletter in the 1990s led to a class action hostile workplace lawsuit by more than 20 women officers.

Shortly after Chavira entered policing, Sylvia DeAngelis – the first woman to achieve the supervisory position of sergeant in the department – filed a hostile workplace lawsuit against EPPD’s police union, the El Paso Municipal Police Officers Association, for publishing flagrantly sexist columns in the union’s newsletter.

In 1990, Chavira joined 21 women officers in a class action hostile workplace lawsuit against the union and the Combined Law Enforcement Association of Texas. Then at a monthly union meeting, the women participating in the lawsuit were asked to stand up, Chavira recalled. A vote was called: Should the women officers – all dues-paying members – be kicked out of the union?

A majority voted yes. Many of the votes came from men she’d considered partners and friends.

“That day was really sad for me,” she said. “It was a horrible feeling. I went home and actually cried. Because seeing the faces of the men voting and the anger – you know, a lot of them were really, really angry.”

Despite the vote, Chavira and the other lawsuit participants weren’t ultimately ousted from the union – she’s not sure why. Though a jury supported DeAngelis’s hostile workplace claims and awarded her $60,000 in damages, an appeals court put aside the decision in 1995. The class action lawsuit, which was based on similar claims, was also dismissed a year later.

Excerpt from a lawsuit against the El Paso Municipal Police Officers Association for publishing flagrantly sexist columns in the union’s newsletter (left).

It was out of this environment, Chavira said, that she and other female officers decided to form an EPPD women’s committee.

The committee started small, she recalled. At first, it functioned to swap policing strategies and share knowledge about officers and supervisors who engaged in harassing behavior. Soon, the women’s committee had become a powerful organizing tool for female officers, Chavira said.

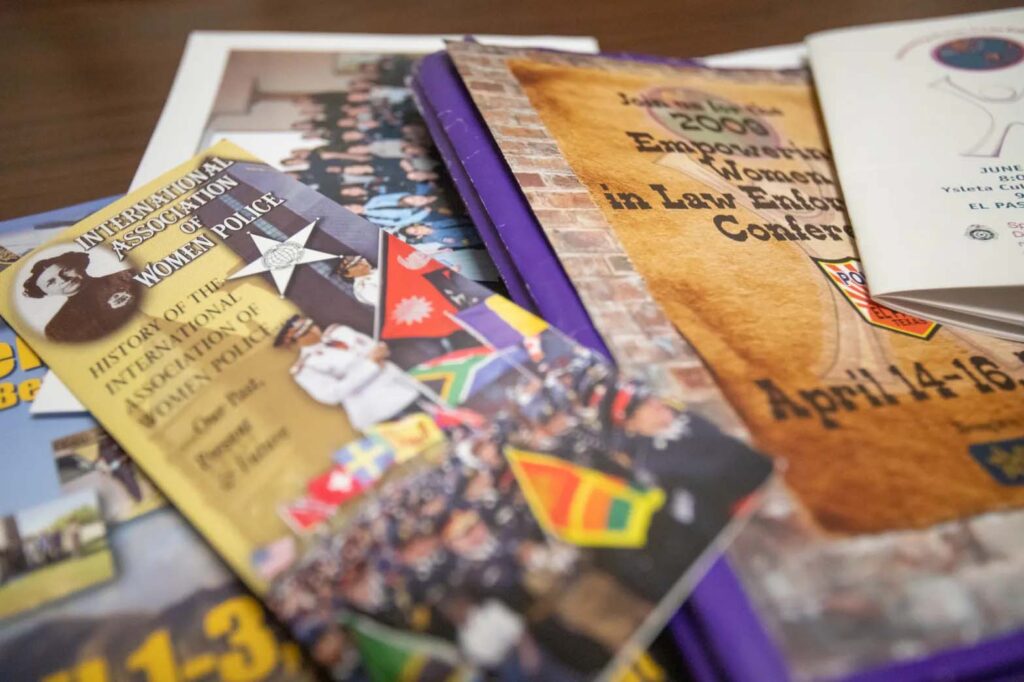

In the early 2000s, the committee began to host a yearly “Empowering Women in Law Enforcement” conference – an event that drew men and women from multiple law enforcement agencies across the country, as well as Mexico. It gave out scholarships to the daughters of women police officers and an award for female officers who had survived traumatic events in the line of duty.

Literature and photos from the now-defunct Empowering Women in Law Enforcement conferences previously held annually in El Paso. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Between the women’s committee and the conference, “I felt very supported,” said Chavira, who went on to become EPPD’s first female bomb technician and now works as the law enforcement liaison at El Paso’s Center Against Sexual and Family Violence. “It felt like the department was moving forward.”

And in November 2007, when then-EPPD Chief Richard Wiles announced he’d be leaving the police force, it seemed that women might crack the highest glass ceiling. As second-in-command at the department, Chief of Staff Diana Kirk was next in line to become El Paso’s first female police chief.

When Greg Allen was chosen over Kirk, she sued the city for gender discrimination. In becoming the city’s first Black police chief, Allen broke barriers himself.

John Wenke

“But you also forget the fact that he leapfrogged over what should have been the first Hispanic female police chief, who was much better qualified than him,” said Wenke, the employment attorney who represented Kirk in the suit.

Kirk outranked Allen, and according to court documents, held more years in high-level supervisory roles; a master’s degree to his bachelor’s degree; and spoke Spanish where he did not. And, she did not hold Allen’s disciplinary baggage – such as his role in assaulting a juvenile to the point that he required medical attention, according to Allen’s own deposition in the suit, and two dismissed sexual harassment allegations against him, which Allen also disputed in his deposition.

In a deposition, then-City Manager Joyce Wilson testified that she’d selected Allen over Kirk because she wanted a “Warrior leader” over a “Wizard leader,” according to a petition Wenke filed in the case. In a separate deposition, the city’s Human Resources director “could not explain what either a ‘warrior leader’ or ‘wizard leader’ was,” the petition continued.

What began as a claim of gender discrimination came to include retaliation, when Allen allegedly stripped Kirk of her job duties following her lawsuit. In a January 2009 meeting between Kirk, a deputy city manager and Allen, who was wrapping up his first year as police chief, according to a petition filed in the case, “an angry Chief Allen yelled at Chief Kirk telling her, ‘I gave you good advice and I told you not to file this lawsuit’ … ‘your career is over’ and ‘now no one will hire you.’”

In 2010, the city of El Paso entered into a settlement agreement with Kirk, which included non-disparagement clauses barring both parties from publicly speaking negatively about each other.

Kirk “was a trailblazer,” said Wenke, her former attorney – one of many women at EPPD to “crack the glass ceiling, so to speak. But they’re still just that: cracks.”

Disbanding progress

The last Empowering Women in Law Enforcement Conference was held in 2010. After that, both the women’s committee and the conference were disbanded – with no explanation offered to participating officers, Chavira said.

Teresa Chavira, law enforcement liaison at the Center Against Sexual and Family Violence, recalls the annual conferences on empowering women in law enforcement that used to be held in the El Paso region. Chavira saved programs and other literature from the conferences when she retired from El Paso Police Department. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

In an email last fall, a city spokesperson said EPPD had discontinued the conference due to funding shortfalls.

Chavira questions this reasoning: The conference and the committee had long relied on outside fundraising, she said, and were largely, if not entirely, self-sufficient. She showed El Paso Matters conference brochures thanking dozens of sponsors, though it’s unclear how much the sponsors contributed financially.

The city did not respond to follow up questions relaying Chavira’s concerns.

The abandonment of the conference was soon followed by an end to specialized email listservs for the Police Department – among them an email distribution list exclusively for women officers. Chavira said the list had been one of their main avenues of organizing, community-building and communicating about discriminatory behavior.

The support system Chavira had worked decades to help build swiftly deteriorated. “It was like a door closing,” she said.

In September 2012, a female police sergeant attempted to reinstate the listserv for women officers. “As a result, several female officers reported incidents to me these female officers felt were discriminatory,” Sgt. Lourdes Calderon wrote in an EEOC complaint, obtained through a public information request.

The department swiftly shut down the distribution list again, Calderon wrote, and “began to retaliate against me in several ways,” including having the email distribution list removed. She also cited not being allowed to meet to discuss complaints received by female police officers, as well as being denied sick leave and being placed on absent without leave status.

‘We can’t squash history. If you don’t learn from history, it’s bound to happen all over again.’ – Retired EPPD Officer Teresa M. Chavira

Chavira, who was recently appointed to El Paso County’s new Women’s Commission, retired from the Police Department in 2013. It was a job she adored, despite its challenges. When she tries to discuss those challenges, she said she’ll often get asked: “Why are you bringing that old stuff up?”

“We can’t squash history,” she said. “If you don’t learn from history, it’s bound to happen all over again.”

Gender discrimination takes many forms

Gender discrimination at EPPD takes many forms beyond overt sexual harassment, Carrasco said. It includes hostility toward breastfeeding mothers and a lack of paid parental leave.

Neither the city nor the Police Department offer paid parental leave to new parents, forcing them to rely on their accrued vacation or sick days, leave donated by co-workers, and up to three months unpaid leave under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act.

When Chavira had her first child in 1993, she went about two months without pay to care for her newborn. This fall, the detective found herself in a similar situation with the birth of her third child.

In her role as a detective, she does not go out regularly on patrol, but if there’s a sting or a search warrant, “I’m expected to throw on my vest and go kicking down doors,” she said. “A few months after having my child and then having to go back to that – that’s insanity to me.”

The detective says she’s seen new mothers forced back onto patrol shifts before they’re mentally or physically ready. Beyond the actions required of a patrol officer, she noted that the police uniform alone – like wearing a 12-pound gun belt across your midsection – can pain someone who’s just had a C-section, a major surgery that can take months of recovery.

The parental leave policy also hurts fathers, said a male officer with more than 10 years in the department. “It’s very detrimental to child rearing, getting to have that bond with your child – you just can’t do it,” said the officer, who asked to not be identified to protect his career. “It puts a strain on these relationships, not just with your child, but with your marriage partner or the partner you’re involved with.

Parents who want to breastfeed at EPPD also face challenges. Federal law requires employers to provide a private lactation space that’s free from intrusion – and not a bathroom – and allow workers to breast pump for up to one year. They also have to give employees a reasonable amount of breaks and time to express breast milk. In April, an enforcement provision of new federal legislation known as the PUMP Act took effect, allowing workers to sue employers who aren’t in compliance.

Cynthia Calvert

To begin breast pumping at EPPD this winter, the detective said she was required to submit a doctor’s note. According to current EPPD policy, officers seeking a lactation room “must give a minimum of 2 weeks’ notice to their supervisors” to allow time for the accommodation.

“If the policy says that officers ‘must’ provide two weeks’ notice, that implies that the officers could be denied use of the lactation room if they do not provide the notice. That would violate the PUMP Act,” Cynthia Calvert, an employment lawyer and senior advisor at the Center for WorkLife Law at the University of California – Hastings Law School, wrote in an email to El Paso Matters. “Bottom line: the department cannot fail to make a suitable space available for pumping if an officer needs to use it – even if the department just learned about the need.”

Half the department’s existing command stations have no lactation rooms, per EPPD’s response to a public information request. This means that many officers seeking lactation space must transfer stations; according to EPPD policy, they “will be temporarily assigned to (Police Department) headquarters or other (Police Department) facilities that have an HR-approved lactation room.”

Calvert called this practice “a dicey one” that depends on how the transfer impacts the officer’s career. “If the transfer affects the officer adversely, the department could face retaliation claims under the PUMP Act and/or discrimination, harassment, or retaliation claims under the federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act,” she wrote.

Neither EPPD nor the city responded to El Paso Matters’ questions about these policies.

Across the department, there also is widespread disdain for women officers with children, and a perception that in asserting their federal right to breastfeeding or pregnancy accommodations, they are abusing a privilege, Carrasco said.

She pointed to a term – “milking it” – that officers use to describe someone who’s lazy, which she’s heard applied to nursing mothers. “They’re given the derogatory verbiage of ‘milking it’ if they want to breastfeed their child for a year, because you can’t be in a uniform if you breastfeed, and you need a break to breastfeed,” Carrasco said.

“One of my hardest working females, she breastfed a year. She was the best working detective I’ve ever had – and I’ve had great detectives, so that says a lot. She (went to) call outs, she did everything. She just needed time to breastfeed her daughter. And there were even other females who were like, ‘Oh, she’s milking it,’ and you’d hear it from guys. And it’s just incredible that this is the mentality toward this fantastic worker.”

Neither the department nor the city provide child care or child care subsidies for their workers. “I was a single mom for about four years,” the detective said. “And so child care issues, those are things that we have to pay for, those are things that the department doesn’t care about.”

She and other women interviewed for this story described being written up by supervisors for arriving 10 minutes late to work after dropping off their children at school – and little flexibility in shift rescheduling to accommodate parenting obligations. “It’s like, ‘who cares – child care is your issue’ type of thing,” the detective said.

She and Carrasco had hoped that reviving the women’s committee would be a first step in addressing these issues. After that proposal was shot down, they tried again – this time with city leaders.

In September 2022, Carrasco, Chavira and retired Sgt. Linda Hanner met with City Manager Tommy Gonzalez, Human Resources representatives and other city staff to raise their concerns. In advance of that meeting, they sent another memo outlining a broad array of policy suggestions to improve the department’s culture and policies.

Nothing has come of their meeting with Gonzalez, Carrasco said. “We talked to him about everything, and he listened. But I never received follow up.” Gonzalez was fired by City Council in February but remains on the job through late June.

This spring, the detective also tried without success to get the police union to push for paid parental leave in its collective bargaining negotiations with the city. The union did not respond to an interview request seeking to discuss the detective’s claims or the gender discrimination lawsuits filed against it years earlier.

“It’s so hard to stay motivated and hopeful that some sort of change will happen,” the detective said, noting that the department does not need to wait for a new police chief to enact that change.

“Any (assistant) chief could go down to the Planning and Research department and say, ‘Hey – the sexual harassment, our officers’ off-duty conduct, is unacceptable. I need you guys to create a policy that directly reflects this in our stance or views on this type of behavior.’ And they haven’t.”

The detective, for her part, is not waiting on department leadership. This month, she passed a Texas Commission on Law Enforcement certification test, paving the way for her to start designing curriculum for the department. She wants her first training course to center on the psychological impact for victims of sexual misconduct – a topic that hits close to home.

It could be a long time before she’s able to teach that course. In September, a city spokesperson pointed to a new “Women in Policing” course as an example of EPPD’s efforts to support women officers; the course had been in development since 2018, and would start that very month, the city told El Paso Matters. Follow up records requests show that as of March, that course still hadn’t been offered.

The detective is well aware of such obstacles, but is still intent that a course she teaches might one day contribute to change.

“If I get to that point, I’ll feel more empowered than anything,” she said. “I’ll have reached the point where I’m going to tell these officers – and I’m not going to know who agrees and who doesn’t – but I am at least going to have a platform now to say, ‘This is wrong,’ – and say it loud.”