This is the second story in Texas Public Radio’s three-part series “Justice Ignored: Texas has a long way to go in helping child victims of sex crimes.” Read the first story here and the third story here.

An executive at a foster placement agency headquartered in San Antonio was accused in 2020 of sexually assaulting a child. But TPR learned his employer kept him on staff — as the highest paid employee — months after the allegation.

Even after the state child welfare investigators found “reason to believe” he had sexually abused his great niece for eight years in June 2020, his employer delayed acting. Also, several former staffers said his departure from a leadership role even extended past when the agency said he had been terminated.

Gerald “Jerry” Monroe was the chief financial officer of Texas Foster Care & Adoption Services when he was arrested in December 2020 for the alleged repeated sexual assault of his great niece, Shawna Rogers. TPR learned that Rogers wasn’t the only woman who accused the now 71-year-old Austin resident of sexual impropriety.

Shawna first came forward in 2020 with allegations that the man molested from the age of 8 years old. But the case against Monroe was dismissed in 2022 due to Rogers’ death.

Shawna Rogers with her half-brother.

Courtesy Robin Farris

TPR’s investigation of Monroe, his employment and the allegations made against him was based on multiple interviews with former colleagues, relatives, legal officials, prosecutors, along with reviews of tax documents and hundreds of other records.

“It was hush-hush,” said Eric Cartegena, a former member of Texas Foster Care & Adoption Services management staff in San Antonio. “There wasn’t very much transparency with that. They didn’t discuss it with any of the other staff.”

Cartagena said CEO Karen Perez instructed him not to tell any other staff members. He described Monroe as a remote worker who was rarely if ever in the office but who wielded a lot of influence throughout the organization.

The nonprofit’s tax returns confirmed that Monroe worked there through 2020.

The state does not mandate that an organization entrusted to care for children terminate someone accused of – or even arrested for – a crime against a child.

But prosecutors of crimes against children told TPR these accusations usually result in termination.

“Yeah, it’s very unusual (for them to stay on staff),” said Nick Socias, a special victims prosecutor in Kendall County. “I’ve prosecuted a foster parent who, the second the allegation came to light with him, all children were removed. His license was pulled. A teacher — same exact thing. A CPS worker — he was terminated that day.”

One foster placement official with a larger agency said a “reason to believe” abuse finding with the state was very serious, and it was unlikely that person would remain employed with their agency.

And yet, Texas Foster Care & Adoption Services waited six months, telling state licensors that it fired Monroe the day before Christmas 2020, two days after he was arrested by Austin police for sexual assault of a child.

“I’m not going to discuss this with you,” Perez said when TPR asked her about the gap.

TPR highlighted problems in the police investigation of Monroe in part one of this series.

Jerry Monroe

Police waited eight months to arrest Monroe. Rogers died in a car accident in October 2021. The sexual assault case against Monroe languished and was ultimately dismissed in early 2022. According to court documents, it was dropped because of Shawna’s death.

Monroe maintains his innocence.

From the time CPS launched its investigation in early April to his arrest in December, his role at the agency did not appear to change, five former colleagues said.

One former employee said that Perez confided not long after his arrest that Monroe hadn’t passed his background check in early 2021. But rather than fire him, they scrubbed his name from agency documents.

“His name was removed from everything, and I never heard he had been fired. I kept in contact with other folks there (after departing), and he is still working there,” said the former employee, who wished to remain anonymous.

Cartagena said Perez told him that Monroe was removed from the nonprofit’s board of directors after the allegation was made.

But Monroe was present at board of directors meetings through 2020 and by all appearances able to continue in his role at the agency — which included him weighing in on decisions, employees said.

“They were still discussing programs and agency things that they needed to be done with him,” he said.

It wasn’t clear what Monroe’s involvement was after spring 2021, Cartagena said, but through his tenure that ended in March 2022, he was never told Monroe was fired.

Amanda Benavidez, another former employee, confirmed the account and said staff didn’t talk about Monroe but if a decision needed to be made — he was called. She said she thought it continued through 2021.

“Any big decision, and Jerry’s name came up and he was consulted,” she said.

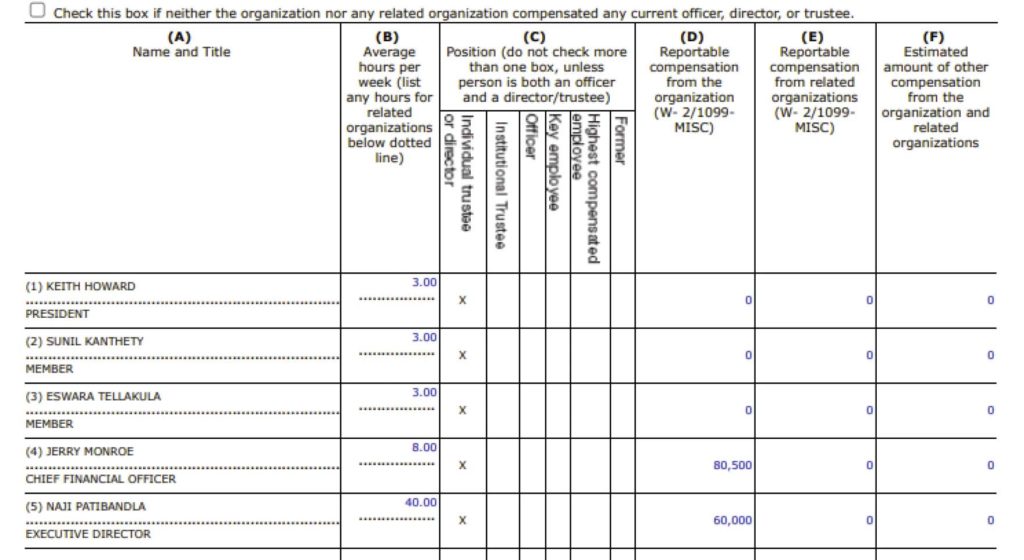

It wasn’t clear if they were or still are paying Monroe. At the time of publication of this report, the agency had not filed its 2021 tax returns. The 2020 filings indicated his salary may have been removed from the executives section.

“He doesn’t work here,” Perez said, “Probably a while ago, almost two years.”

TPR emailed a dozen questions to Perez for this story after she declined to answer them on the phone.

They included queries about when the agency learned about the allegations, whether or not Monroe or his wife still work for the agency, and whether they took action to limit his access to agency youth after allegations surfaced.

Texas Foster Care & Adoption Services 2016 tax form. Despite Karen Perez being elevated to CEO the following year, neither her name nor her salary were listed on subsequent tax forms. One expert called that a “red flag.”

IRS

‘Like listing your dog’

The organization had other irregularities on its tax filings, according to one expert.

For example, Karen Perez’s LinkedIn profile indicated that she was chief executive officer for more than four years. But she was not listed on any of the tax documents, which require key employees who are running the day to day operations to be listed along with their salaries.

Her absence from the documents is a red flag to the IRS that could trigger an audit, said Marc Owens, former director of the IRS Exempt Organizations Division.

“It’s like listing people who aren’t your child as a dependent on your 1040. It’s in that category, like listing your dog,” said Owens, who is a partner at Loeb & Loeb LLP.

Perez agreed with TPR that she was a key employee but said she didn’t sign the tax form, commonly referred to as a 990.

“I’m done with this conversation. We do have an attorney, and we’ll make sure we get that number to you,” she said before ending the phone interview.

In interviews with past employees, they pointed to other issues they saw with the organization.

Perez hired her son to conduct fire and safety inspections. Former employees questioned the necessity of the position because the job used to be done by case managers. Also, staffers said for years they were told Perez’s daughter-in-law Sheila Perez was the nonprofit’s executive director. But she was not mentioned on the tax filings either.

Naji Patibandla was listed in that position on the tax documents. Patibandla did not respond to TPR’s request for comment, and the agency did not answer the questions TPR emailed it.