People who don’t ordinarily weigh in on political debates are jumping in to respond to the Trump administration’s so-called zero-tolerance policy that separates families accused of crossing the border illegally – including a Midland native named Laura Bush. The Republican former first lady, who now lives in the Dallas area, penned an opinion piece for the Washington Post this weekend, describing the practice of family separation as cruel and immoral.

“Our government should not be in the business of warehousing children in converted box stores or making plans to place them in tent cities in the desert outside El Paso,” she said, referring to the temporary detention camp for migrant children in Tornillo, Texas.

Lomi Kriel, an immigration reporter with the Houston Chronicle, says there is no law that requires the separation of families.

“But there is a law that makes it a federal misdemeanor to cross between a port of entry,” she says. “And so what the government is saying, that they’re now fully enforcing that law, that nobody is exempt, and they’re prosecuting anyone who crosses between a port of entry, and that parents who come with their children are not going to be spared from that.”

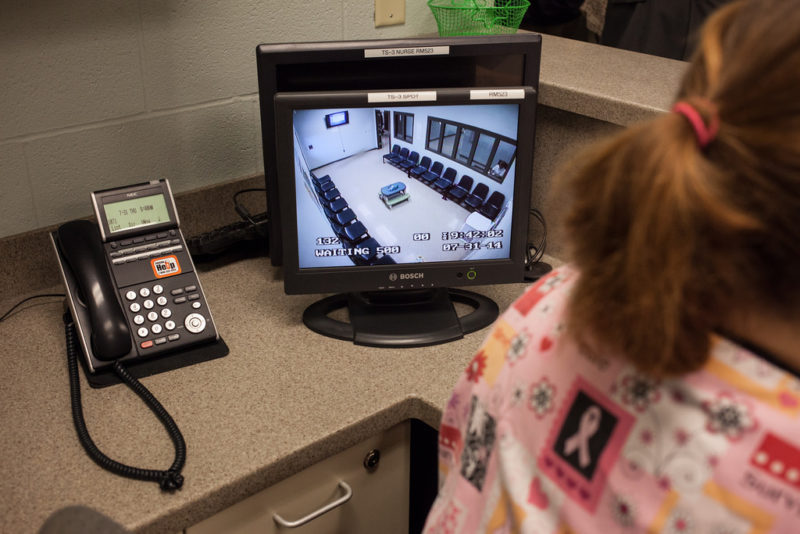

Detention involves a complex set of procedures that can be difficult to follow. Here’s how it works once border patrol has apprehended a family.

“They would take that parent and child to the processing center and decide to refer the parent for prosecution,” Kriel says. “The parent would stay in the border patrol holding cell for maybe a couple of days, and then go to federal court, plead guilty quickly in kind of like an hour’s long mass plea hearing, and usually get sentenced to time served or just a couple of days. Serve that time, and then they go back to the custody of immigration detention for their deportation.”

By that point, Kriel says, the children have been transferred to Health and Human Services, which takes care of unaccompanied minors.

“That launches a whole process and puts them on a separate track,” she says. “They’re put into a federal shelter for unaccompanied immigrant children, and supposedly they should then be reunified once their parents have served their criminal sentence. But because they’re now kind of, like I said, on this separate track, advocates who work with children say that it’s really difficult often to reunify the parents and the children.”

Kriel says the federal government contracts with nonprofit organizations to run the shelters that are licensed by the state to hold children.

“[The Department of Homeland Security] says that reunification happens once the parents serve their sentence and go back to immigration custody,” she says. “But we know from multiple accounts and from advocates who work with the children and with parents that this does not always happen and we know in some cases parents have been deported alone, without their children.”

The Trump administration says the policy is meant to be a deterrent to parents who are considering crossing the border.

“I think the message is getting out,” Kriel says, “and I think parents are terrified about this. Many of the parents that I’ve heard in federal court who were asking the judge to help them find their children, they said, ‘I just want to be deported with my child. If I’d known this would happen, I wouldn’t have come.’ But on the other hand, in McAllen last week I spoke to a Catholic sister Norma Pimentel, who runs the Catholic shelter there for immigrants. And she said that she talked to these parents and that they were really afraid of this new policy, but that they told her, ‘We’re still going to come, because it’s worse for us if we stay.’”

That’s why, she says, the decision to cross the border depends on a family’s individual circumstances.

“If a gang in El Salvador is threatening to take your daughter and force her to be part of them,” Kriel says, “you might take the risk and see what will happen if you come here.”

Written by Jen Rice.