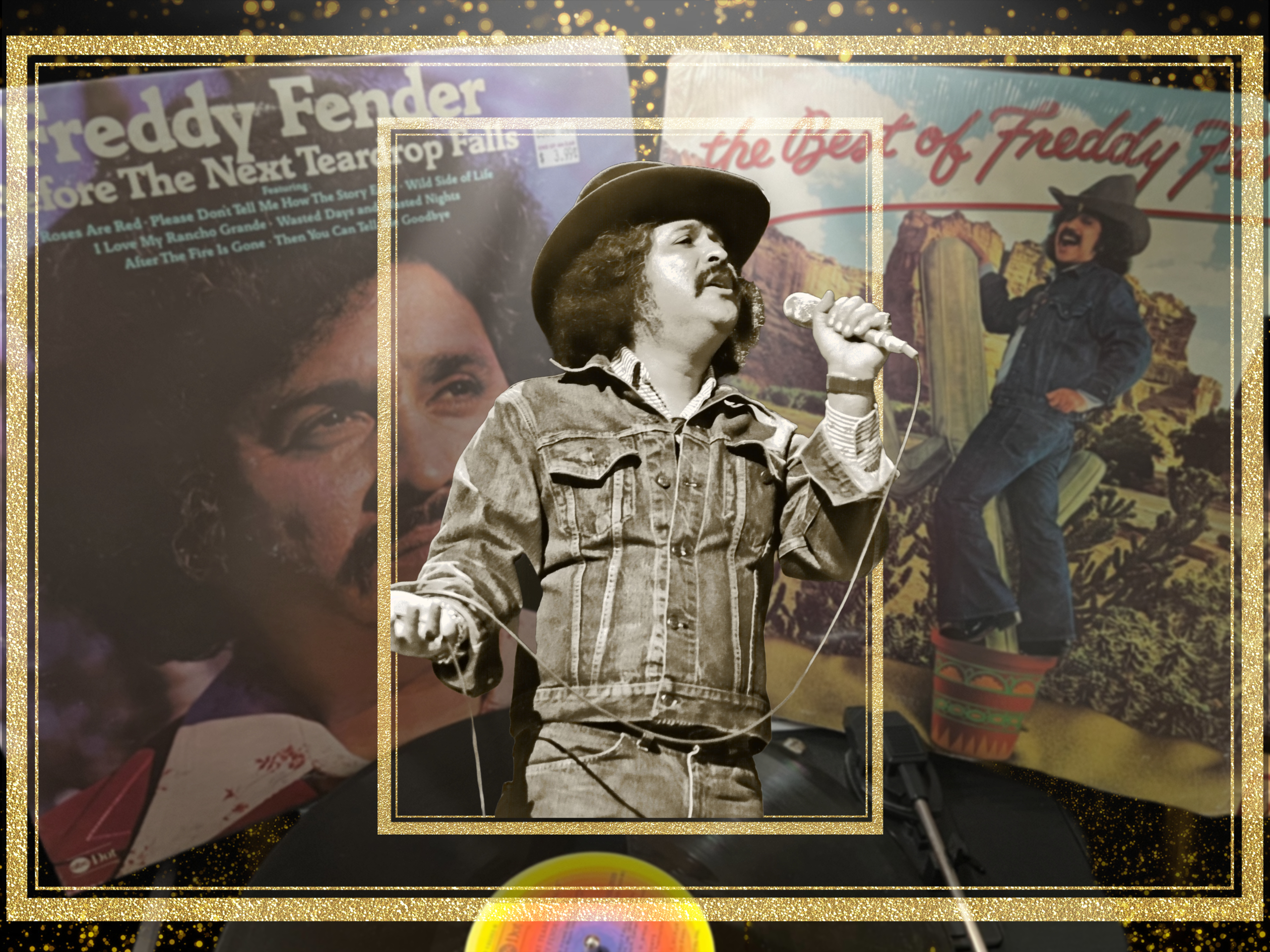

Freddy Fender’s legacy in country music has withstood the test of time for generations. His Texas roots and Mexican-American heritage are what made Fender, born Baldemar Huerta in the Rio Grande Valley, one of the first Hispanic rock ‘n’ rollers to top the Latin American Charts in the late 1950s.

The Country Music Hall of Fame, which was created in 1961, currently has 146 members. In 2000, the great Charlie Pride became the first African American to be inducted. But to date there are no Hispanic members. Veronique Medrano, a singer and Tejano music archivist, says that’s a huge oversight and wrote for Wide Open Country about why Fender would be the perfect nominee. Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: You wrote “Freddy Fender was truly the embodiment of the American dream, a migrant worker who came from a small town and worked hard to build a name for himself to provide for his family.” Before he was Freddy Fender, he was “El Bebop Kid,” right?

Veronique Medrano: Yes. That was the first recording that he did for a label out of Mexico or pretty much in the frontera [border] area. He released music under “El Bebop Kid” literally months before the rise of Ritchie Valens. So at the same time that both of these people are getting big in the bebop era, him for the Latin American audience because he was big in South America, he was big in Mexico, but just wasn’t big in the States. So he released a cover of Elvis Presley songs. He had done a Spanish version of “Don’t Be Cruel.” And that was the song that literally hit No. 1 on the charts in Latin America.

But I wonder if he would have been as big as he became had he not ultimately changed his name to Freddy Fender, as most people knew him.

I will say that because of the times, him switching to Freddy Fender after his success in Latin America was really telling, because during that time … having a Hispanic last name was not something that would really get you that audience. You needed to have an Americanized persona.

If you look back at the country music charts, right around 1975ish, we’re talking about songs like “Secret Love;” ‘You’ll Lose a Good Thing,” the old Barbara Lynn song; “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” – they all reached No. 1 on the Billboard country chart. That’s huge. I mean, how many people can make that kind of claim?

Very few. And he was not on, like, a huge label. We’re not talking about the big labels of, like, Sony and Capitol and the names that people recognized for the time. For him to be able to to do this and not be from Nashville, that’s another huge thing to think about as well. For him, it was, you know, “I want to represent who I am.” And he did that so beautifully.

But it did require sacrifice. It required the sacrifice of his name. But when you think of the legacy that he left behind and the fact that towards the end of his career, he was able to win a Grammy under his name, the Ballads of Baldemar Huerta, and winning a Grammy in that sense, towards the end of his career, it’s almost like a full-circle moment. And if you look at the six decades – that’s 60 years of active musicianship – and, you know, the minimum for the Country Music Hall of Fame is, if I’m correct, it’s like 25 or 30. It’s so unfortunate that not even the work, not even the Grammys, not even the Billboard-charting tracks.

You touched on a lot of important factors there. One of them is the lack of Nashville connection. Sure, he had some great session players playing on some of his stuff, but he was a Texan and he really identified with Tex-Mex, certainly later in his career when he’s part of the Texas Tornados with Flaco Jimenez and Augie Meyers and Doug Sahm – I mean, a Tex-Mex supergroup, if there ever was one. Then you’ve got the fact that he didn’t get his start on one of these major labels. So I wonder how much of the industry has been a part of the way his legacy has been left out, certainly when you’re considering a figure who has accomplished as much as Freddy Fender has.

Exactly. And it’s the question that I have. It’s the reason why I wrote what I wrote. And it gets me so emotional thinking about the fact that two years before he passed, he was attempting to vouch for himself, campaigned for himself to be inducted, and that it never happened. It’s been 17 years. And yet here we are with not a one, not Johnny Rodriguez, not Linda Ronstadt, not Rick Treviño, not Freddy Fender. No one in the Hispanic community has been recognized by the Country Music Hall of Fame, and there’s no response from them for it or why.

I have to say, I was moved by the fact that you got so emotional about this. This is personal for you, it sounds like.

You see somebody that looks like you, you see somebody that does music like you – bilingual country music –and you see how little it’s acknowledged. It’s like, you know what? We should be recognized. All of us, every single person from Freddy Fender to Linda to Rick Treviño. I mean, my God, he was part of two supergroups, I realized, [also] “Los Super Seven,” performed with Dolly Parton on her TV show. I mean, there’s so much that can be said about Freddy that just can’t be contained in a very short amount of time. But when you see that, it just seems so crazy that he’s not a part of that very elite aspect of musicianship that just seems obvious that he should be.