From Texas Public Radio:

With Amanda Gorman’s electrifying poetry readings at the inaugural and the Super Bowl, many of us are taking a second look at poetry. TPR’s Arts and Culture Reporter Jack Morgan was reminded of a poetic memory from 15 years ago. That something came from this guy: Dimitri Lotovski.

“I live in Atlanta right now. I’m a cameraman and editor for a local CBS affiliate. And I’m from Kiev, Ukraine originally,” he said.

He emigrated to the U.S. in the 1990s and I worked with him at WOAI TV. One day in conversation he let slip that his dad wrote a poem about Jazz.

“My father was a big lover of Jazz, yes, and literature and the arts, just was an enlightened man, nothing like me,” he laughed.

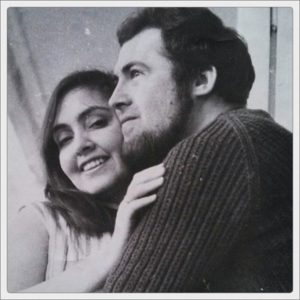

Asya and Yakov Lotovski

His father Yakov was born in 1939, and so as a child and young man, he saw some very dark times in Soviet history. As an adult, he spent much of his spare time writing, primarily short stories that were both dark, and funny.

“My dad was a writer, but he never really worked as a writer in Soviet Union because he wasn’t part of the system. He wrote, as they said back then, into his desk.”

“Into his desk” meant the work wouldn’t be published, but stayed there at his desk. Americans may, all these years later, forget that the Soviet Union era under Joseph Stalin was an authoritarian nightmare for creative types.

“Soviet writers were expected to propagandize the Communist Party in their writing and be members of the Communist Party,” he said.

And Lotovski wasn’t just a free spirit who didn’t want to play the game. He was also Jewish.

“Being Jewish was a giant handicap for him. And I remember that he was telling me that the Jews who wanted to make it in the Soviet System had to kiss ass twice as hard. Of course, he wasn’t gonna do that,” he said.

Post World War II was pretty extreme for Russians. At least 20 million died in the war, and the country’s infrastructure was heavily damaged. Although Hitler’s defeat was an incredible victory for the Russians, after the war Joseph Stalin’s reign became even less tolerant.

Dimitri in his Soviet Army days, with mother Asya.

“Stalin decided he’s better to get ready for World War three and get discipline back,” Dimitri said.

“And it was dark times. And that’s what my dad is talking about in his poem.”

Dimitri’s father Yakov wrote The Sound of Jazz poem. Here Dimitri reads part of his dad’s opening stanza. In the verse, Yakov is a 7-year-old boy hearing his uncle just saying the word Jazz. It’s incredibly vivid.

I remember very clearly when he said Jazz, his gold tooth shined, and the silver one in the depth of his mouth. He pronounced it with a slight and sad smile with which people speak about something unreachable, and then suddenly he came to his senses and looked cautiously at the door. Back then there was this habit to look cautiously at the door. That’s how the idea of jazz entered me as something bright, exotic and forbidden.

The Sound of Jazz

To young Yakov, the word Jazz was itself magic. It had a power that seemed to threaten the Soviet system.

“He didn’t know what it meant when he was a boy listening to his uncle say that word, but the word entered him as a forbidden fruit,” Dimitri said. “Then later he realized that that was what happened. He got infected by the western idea of freedom.”

It wasn’t just in Yakov Lotovski’s imagination that the concept of jazz was seen as a threat to the Soviet Union.

“In Russia in the 1940s there was a propaganda saying. In Russian it sounds like this: ”Сегодня слушаешь ты джаз а завтра родину продашь!“ “…which means ‘today you’re listening to jazz and tomorrow you will betray your motherland,’” he laughed.

The poem was borne of a paranoid time of Stalin purges. Dimitri conjures the setting where it first took shape.

Yakov Lotovski (center, seated) takes in some Jazz on the streets of New Orleans

“Just imagine them sitting in a cramped apartment, talking and drinking, most of them are Jews,” he said. “They survived the Nazis, but they don’t know if they’re about to face another existential threat, this time from Stalin. Stalin was planning on sending all the Jews to the far east.”

But before he could do that, in 1953 Stalin died. Then a slow thaw began and as the door to outside culture swung open, Dimitri’s father took full advantage of it.

“I remember when he was telling me when he saw this French band Michel Legrand Orchestra play in the park,” Dimitri said.

“And he was hearing it live for the first time he kinda became possessed. He got up on the bench and started, don’t know what you would call it…dancing, jerking around. It was very unusual for the Soviet Union in the 1950s. People are looking at him like he was mad.”

Dimitri’s parents met, married, and he was born in 1968. Fast-forward to 1989.

Dimitri was in the Soviet army and he returned from Kazakhstan, where he’d been stationed for two years. The Russia he returned to had rather suddenly changed.

“Gorbachev was on vacation and the leaders of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus got together and decided that Soviet Union is no more,” Dimitri said. “I went from Kazakhstan to Moscow and I couldn’t believe my eyes, what was happening. Hippies, you know, rock and rollers walking around with the funny hair. I knew the country changed.”

The Soviet Union dissolution further opened the possibilities, and his uncle Sasha went to live in Philadelphia.

Yakov takes Natasha for a deep dip

“So I went for a visit in 1992, and as I was going there, my parents had this application that somebody left with them for a permanent move to the United States. And that form was very rare to even have,” he said.

On a whim he filled it out, adding his parents and his new wife Natasha. He visited uncle Sasha in Philly and forgot about the form. Then a year later, he got a response from the U.S. Government, giving him an interview in Moscow. After that interview, the U.S. said yes.

“And I thought, oh, my God, I don’t know if I want to move!” he said.

He struggled with whether or not to go, but then decided.

“What kind of loser would you have to be to say, I’m scared, I’m not going. I’m just going to stay here where everything is familiar? That’s insane. This opportunity is not given to many people, and I had to take it,” Dimitri said.

His parents settled in a Russian neighborhood in Philadelphia, and Dimitri started looking for work at TV stations. The first job he landed was incredibly ironic: Odessa, Texas.

“There’s absolutely nothing in common between the two Odessas. Why that place named Odessa? I have no idea,” he said, comparing the city in Texas to the city in Ukraine.

Dimitri got used to life in Texas’s Odessa, but eventually moved on to San Antonio, and finally Atlanta, where he’s been for 13 years.

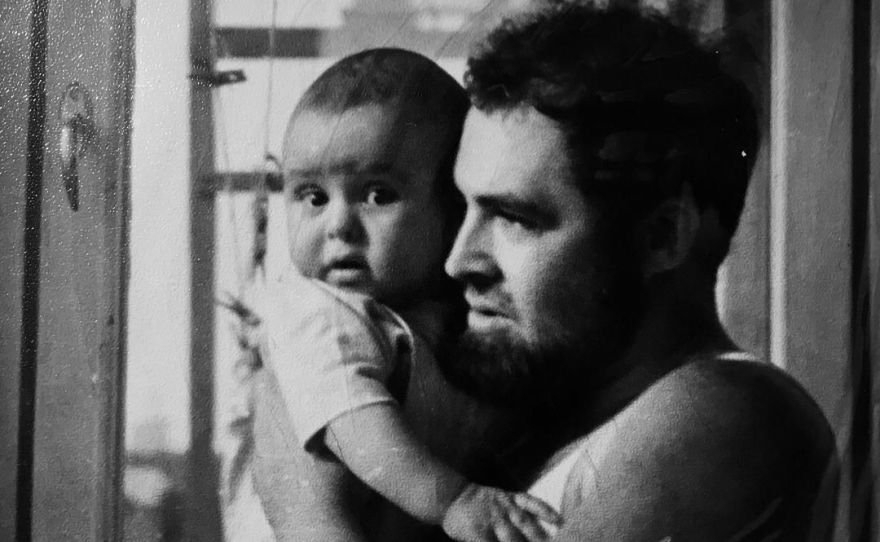

Dimitri, Natasha and Jimmy

His father Yakov had wanted to be a grandfather, and finally that happened just less than two years ago. Dimitri noted that he and Natasha’s carefree life changed instantly.

“Now it’s nothing but responsibilities and obligations. And it’s a funny thing. We love it. The kid turned out to be great,” he said.

They named their son Jimmy, and plan to teach him to read and write the native tongue.

“Part of the reason that I want him to read in Russian is because his grandpa is such a great writer, one of my all-time favorites. Well, right there after Dostoyevsky,” he said.

Dimitri translated the poem from its original Russian, but wants Jimmy to read it as his grandfather wrote it with its natural rhythm and meter, like jazz itself.

Yakov died in May of 2019. In deciding what to put on his father’s marker, Dimitri tried to capture a bit of Yakov.

“On his gravestone it says Yakov Lotovski. A man from Ukraine. A writer and a jazz lover.”