Guillermo Enrique Eliseo née William Ellis was racially ambiguous to say the least. To some he looked like an extremely wealthy businessman. To others he looked like a black man.

In the mid-1800s Ellis was born into a family of slaves in Kentucky. Like her mother before her, Ellis’ mother was raped by a white man. In 1894, when the Confederacy was defeated and slavery was abolished, there was still a legal framework of segregation and a culture of oppression throughout the south. Indeed, many slaves did not realize they were free until June of 1865. The south tried its hardest to keep people who were black in a condition as close to slavery as possible.

But Ellis, who could “pass” for someone of Spanish or Mexican descent, saw an opportunity.

Ellis, his family and his then-master had moved to Texas when Ellis was a child – a big mistake on his master’s part. Many slaveowners were moving to Texas with the idea of setting up a rich cotton industry. But if they had stayed in Kentucky, Ellis’s escape attempt might not have worked out; Ellis could have tried to escape north, where he most likely would have been caught. Instead, the option in Texas was to go south to Mexico – a country that had previously abolished slavery and refused to sign any fugitive slave agreement with the United States. So that’s what Ellis did.

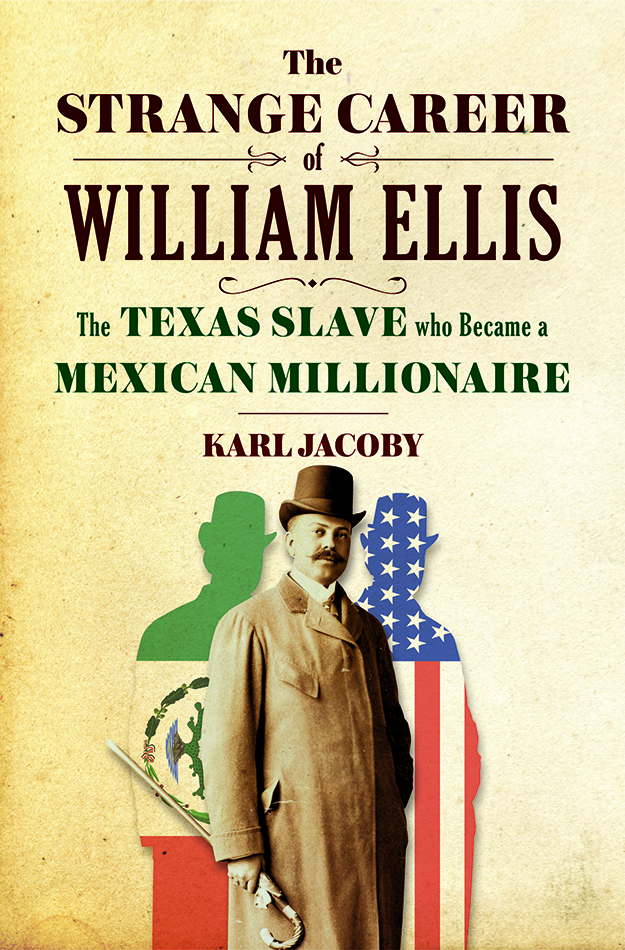

Karl Jacoby wrote the book on Ellis. The book, “The Strange Career of William Ellis,” explores the history of racial lines along the Texas-Mexico border in the 1800s.

Jacoby says he found Ellis’ story in graduate school – almost 20 years ago – when a professor asked him to look through old state department records to see what he could find. As he flipped through what he says were mostly dull records, something stuck out to him. In 1895 there was a migration of 1,000 black sharecroppers from Georgia and Alabama down to northern Mexico.

He followed the trail and found the mysterious William Ellis. Jacoby started collecting any snippets of information he could find about him, but he couldn’t quite get to the bottom of the story.

“What interested me was, not only William Ellis, but I think the perspective that he allows on his time,” Jacoby says. “He was born a slave and then he dies right after the Mexican revolution and so his life really traces this arc where things along the border are just changing dramatically.”

It was a very difficult time for African-Americans, Jacoby says. And the history of slavery in Texas was something he felt doesn’t get as much attention as it deserves. There was this promise of emancipation which shattered in the aftermath of reconstruction.

“Whenever we talk about immigration between the U.S. and Mexico it’s always thinking about Mexicans going to the U.S. We don’t think about Americans wanting to go to Mexico,” he says. “But when you think about what’s happening in the 1890s with the rise of Jim Crow (laws), you can understand why African-Americans would be really intrigued by Mexico – which didn’t have formal segregation.”

At the time, racism and animosity was growing between Mexicans and whites in Texas. There was suspicion that many people of mixed race, who were light-skinned enough to pass as non-black, were living as Mexicans.

“Tejanos posed the most basic challenge any racial order confronted: how to differentiate so-called races from one another,” Jacoby writes in the book. “Not only could physical appearance be ambivalent; so, too, could cultural markers.”

Some former slaves could speak Spanish, giving them an advantage when trying to pass as Mexican.

The book, Jacoby says, gives the possibilities available to blacks on both sides of the border.

Eventually, Jacoby was able to track down some of Ellis’ surviving family members and get his main question answered: “Who was the person behind all these stories that circulated about the fabulous mysterious William Ellis?”

After escaping from Texas to Mexico, Ellis set himself up as a descendent of the Spanish elite. He became a businessman, eventually establishing offices in Mexico City and back in America on Wall Street. He was a stockbroker with influential ties to the Mexican government. Ellis was deeply involved in the scheme to uplift American blacks by relocating them to the colony in Mexico.

As befit the situation, Ellis billed himself as a white Mexican, as a descendant of the Spanish elite, as black, Cuban, and generically “latin.” His racial identity in the press remained fluid. It was well-known among black media and communities that he was black, and in later years, by the mainstream press.

He was the first African-American to travel to Ethiopia from the U.S., using his black identity to gain access and appoint himself a representative of the United States.

In a time of extreme racism and oppression, Ellis was a man who “maneuvered through the tangle of racial identity” on an international level.

Post by Beth Cortez-Neavel.