Prosecutions of “good Samaritans” – people who help undocumented migrants – are rising in the U.S.

Prosecutions for sheltering, leaving food, water and medicines or otherwise assisting migrants have risen since 2017, when then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered the Department of Justice to prioritize such cases. Sessions said the move reflected a new policy of strict enforcement against cases that he claimed were not always prosecuted in the past.

The policy is playing out in Texas and across the American Southwest. In West Texas, a four-time elected city and county attorney, Teresa Todd, is under investigation for human smuggling – a charge she vehemently denies. After working late in Marfa, where she is the city attorney, Todd was driving home on a chilly night in late February when she saw what turned out to be three undocumented Salvadoran migrants.

“I see a young man in a white shirt. He runs out toward the road where I am. I can’t just leave this guy on the side of the road. I have to go see if I can help,” Todd says.

The young man, 22-year-old Carlos Orellana, told Todd that he and his brother Francisco, 20, were terrified for their sister Esmeralda, 18, who was sick and fading.

“I mean, she can hardly walk, she’s very dazed,” Todd says.

The trio took shelter in Todd’s car. Todd called a friend, the senior legal counsel to the U.S. Border Patrol Big Bend Sector, asking for advice.

Unknown to Todd, another driver had passed the migrants and called the Presidio County sheriff’s office. A deputy was dispatched. That deputy crossed from Marfa, in Presidio County, into Jeff Davis County and pulled up behind Todd’s car on the side of the road. The deputy called the Border Patrol. Two agents showed up. One began reading Todd her Miranda rights

“He just said, ‘You’re gonna need to come back with us,'” Todd says.

Todd says she was told that she was under investigation for human smuggling. Eight days later, the government seized Todd’s cell phone.

“It makes people have to question, ‘Can I be compassionate’?” Todd says.

To justify the search warrant for the cell phone, a Department of Homeland Security investigator stated in court documents that he believed Todd “used, is using and will continue” to use her phone to bring in and harbor undocumented migrants.” Todd was taken aback by that revelation.

“This doesn’t feel like I’m in the United States. I’m not a human smuggler,” she says.

“I’m really grateful to her,” says Esmeralda Orellana, one of the migrants Todd helped.

She spoke from the migrant detention center in Sierra Blanca, southeast of El Paso. In July, she was denied asylum in the U.S.

Orellana was the only woman in a group of ten who had crossed the Rio Grande at Presidio. The group, her two brothers excepted, abandoned Esmeralda because she couldn’t keep up as they trekked through the Chihuahuan Desert. By the time Todd stopped, Esmaralda and her brothers had walked 65 miles in eight days. They’d run out of food and water two days before.

“Doctors said I was near death at the hospital,'” she says.

She was admitted for dehydration and life-threatening rhabdomyolysis, a condition the develops as a person’s muscle tissue dies. Dehydration can trigger rhabdomyolysis.

“That happens to lots of people who try to cross that desert and are not prepared to do so,” says federal public defender Chris Carlin.

He represented the Orellana family on criminal charges of illegal entry. Carlin can’t comment on the Teresa Todd case. But he said others in Todd’s shoes in this part of west Texas will often do the same thing.

“There’s a long tradition out here of people helping each other out,” Carlin says.

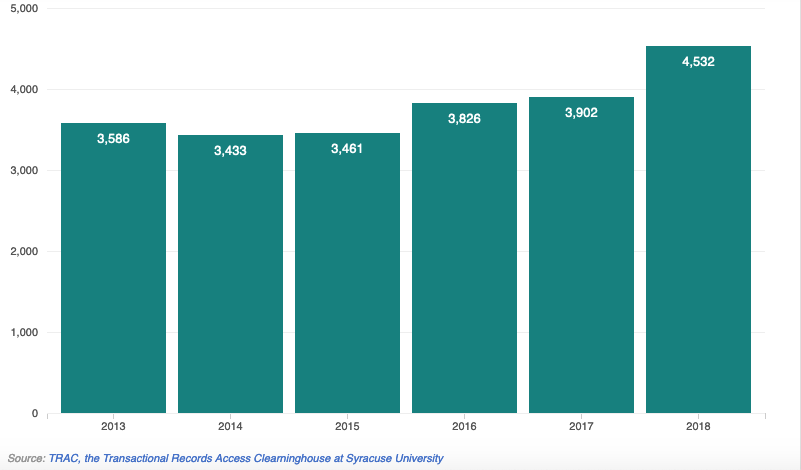

Figures obtained by TRAC, the Transactional Resource Access Clearinghouse, an immigration records analysis center at Syracuse University, show that in fiscal 2018, more than 4,500 people were prosecuted in the United States for helping migrants. There’s been a 30% rise in such prosecutions since 2015. But the greatest rise in that timeframe followed Sessions’ order in 2018.