As the clock ticks down to Election Day 2020, a question familiar to Texans continues to come up: what will be the impact of the Latino vote? But even the phrase “the Latino vote” is too a broad brush for people with so many different backgrounds, personal histories, ideologies and interests.

Benjamin Francis-Fallon suggests the history of this concept of Latinos’ participation in politics may say a lot about what the Latino vote actually is, and what it means for the future.

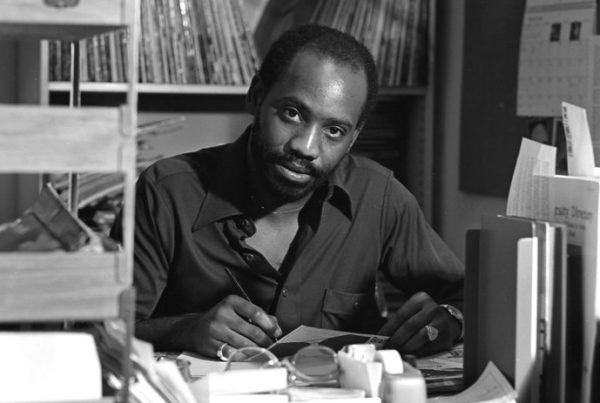

Francis-Fallon is associate professor of history at Western Carolina University and author of “The Rise of the Latino Vote: A History.”

“I think the election in 1960 was a really important moment in the beginning of what we now kind of recognized as being this thing that we talk about: You know, the Latino vote,” he said. “So this was Kennedy against Nixon. And in this moment, Mexican-American activists formed themselves into a kind of a meaningful parallel campaign, which was known as Viva Kennedy. And at certain points in that campaign, the Mexican-American constituency became connected, at least on the surface level, with Puerto Rican constituents. And so that was kind of one of the early moments in which national campaigns began to validate this idea of a nationwide Latino constituency.”

Francis-Fallon said since the late 1960s and early 1970s, the politicians and activists have focused on the different Latino ethnic groups’ similarities.

“Basically,” he said “this society’s reluctance to spend any time differentiating among Latinos came to be something that Latinos tried to turn into a positive by mobilizing their forces for unity and to certain degrees. It’s been successful. There’ve been a number of important institutions established – the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, among others – that trade on the idea that there’s a fundamental unity needed among Hispanic Americans, Latino Americans.”

But this doesn’t always work out.

“I think one of the other lessons that I tried to talk about in the book,” he says, “is that trying to form a national coalition of people from such distinct backgrounds and from some generally weak political positions has in fact different times in the past, at least open[ed] the door to kind of a manipulation of the constituency by forces that would rather see it disempowered, fractured, who would take elevate certain groups in it above others rather than sort of allow it to achieve any form of coherence.”

Click the player above to listen to an extended version of this interview.