When Jackie Loretta saw her son’s health rapidly decline back in January, she feared that she might have to rush him to the hospital.

The unvaccinated 39-year-old took a turn for the worse just a few days after he tested positive for COVID-19. He had a fever and wasn’t eating. He began to lose weight. Loretta said she was ready to drive to his home if things took a turn for the worse.

Fortunately, she didn’t have to. He recovered and was later convinced to get the vaccine after seeing that his fully vaccinated girlfriend did not get nearly as sick as he did.

Loretta believed learning about the vaccine’s efficacy was something her son had to do firsthand.

“He looked at the internet a lot,” Loretta said. “There were so many different things on the internet at one time. Like, they were saying that it [the vaccine] had some type of radiation, or magnetic field in it or something.”

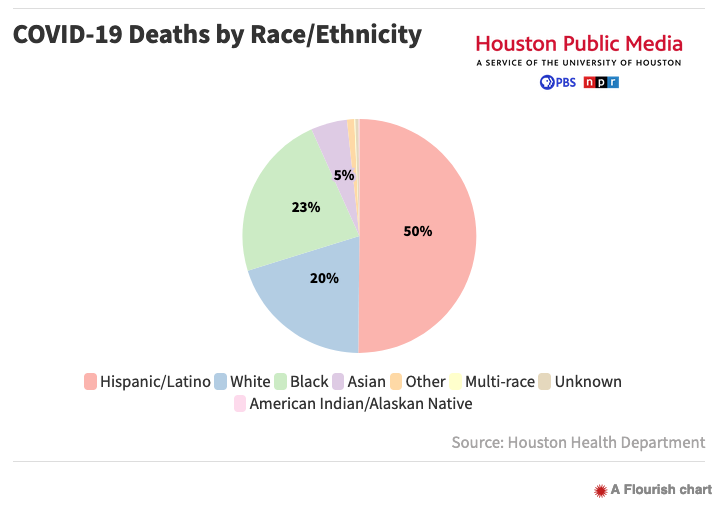

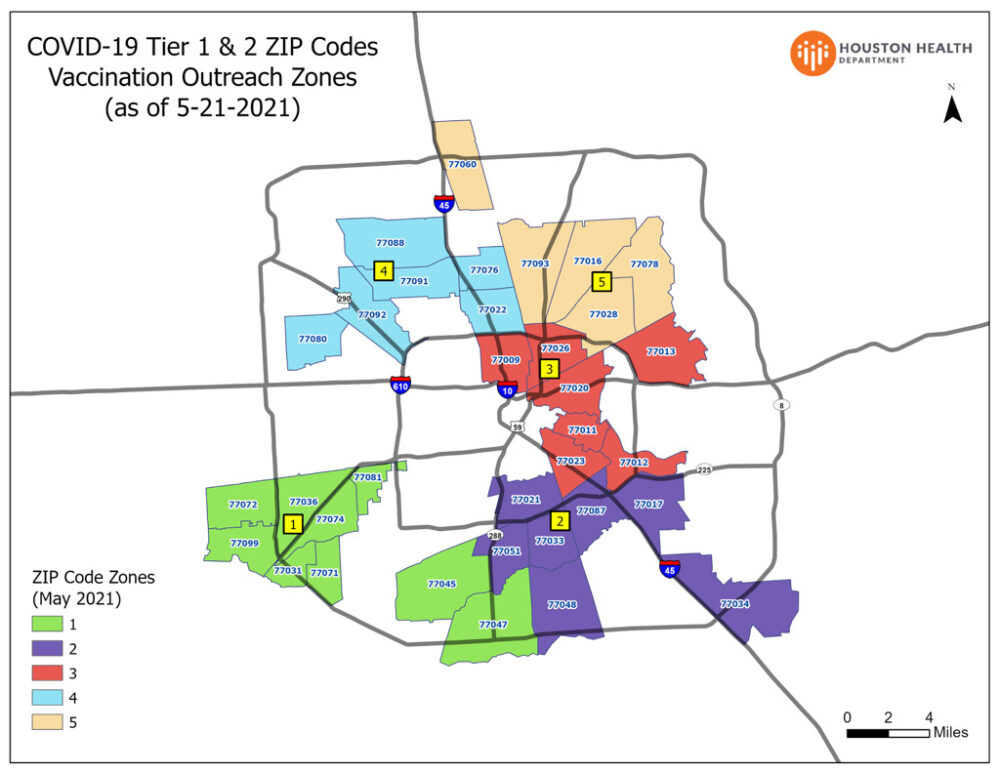

Researchers believe disinformation like this — along with a history of medical distrust — are two of the biggest reasons why just 53% of people in underserved communities of color are fully vaccinated, according to the Houston Health Department. That compares to a 71% vaccination rate in communities not deemed underserved. And Black and Hispanic Houstonians make up 73% of the city’s COVID-19 deaths.

Now, the University of Houston is using a $711,773 dollar grant from the National Institute On Minority Health and Disparities, to learn more about why communities are reluctant to get the shot, and formulate strategies for local government to break down those barriers.

“I think, specifically around distrust and misinformation, you have to first acknowledge it,” said Dr. Faith Foreman Hays, director of the Office of Chronic Disease, Health, Education, and Wellness at the Houston Health Department. “I think you can’t pretend that this is not something that historically has not happened, that people have no memory of.”