“South Texas … that’s where I stay.” Those words from the late rapper Pimp C – edited, fans will note – exemplify the fierce regional pride artists and fans alike have in the Houston-area rap scene.

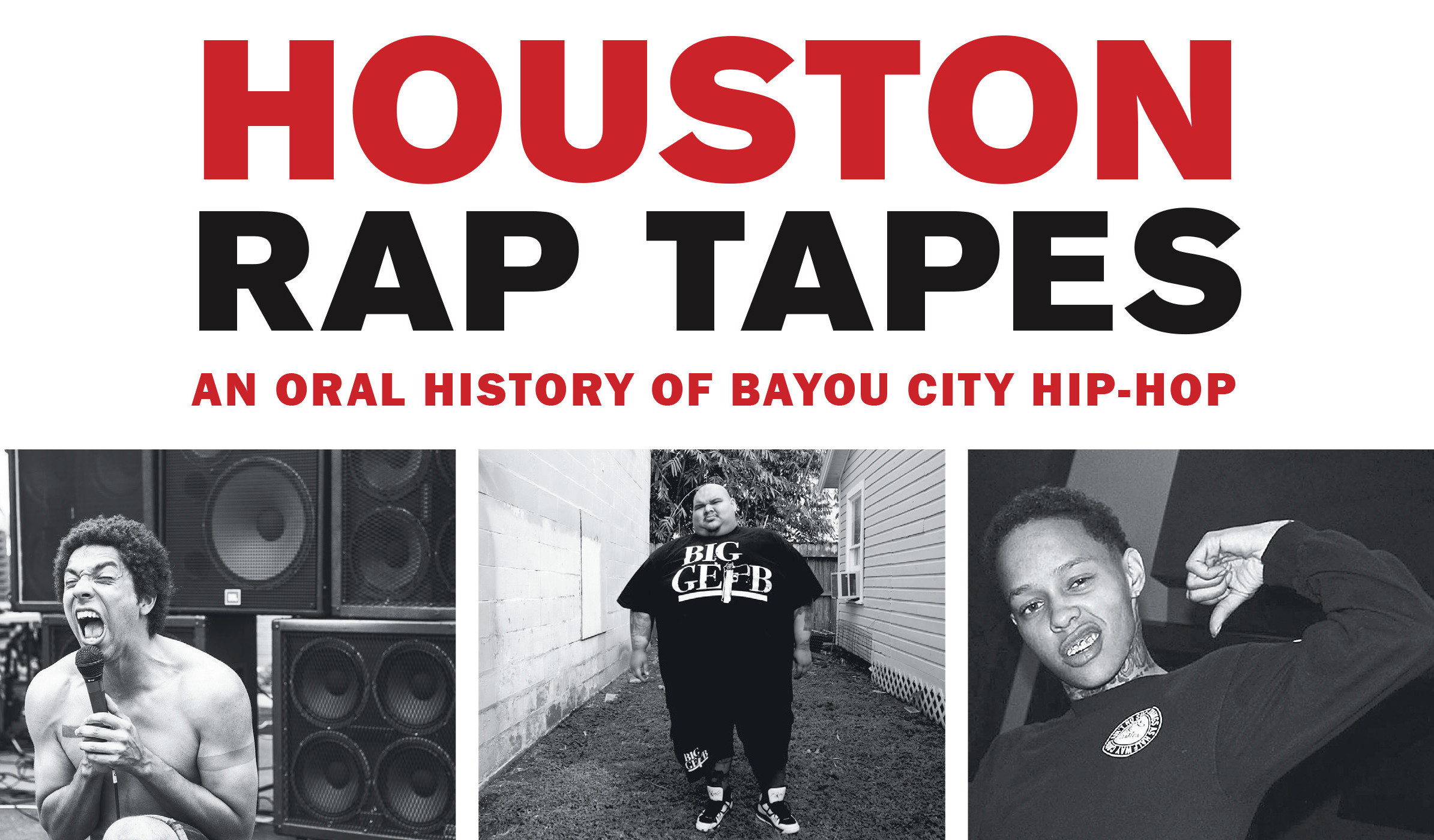

It’s the subject of a new book “Houston Rap Tapes: An Oral History of Bayou City Hip Hop,” which is out this month from the University of Texas Press. It’s an encyclopedic look at the local scene, told over dozens of interviews; it features Texas emcees with platinum-selling records but also lesser-known rappers, producers, promoters and hustlers comprising the lifeblood of Houston hip-hop.

Lance Scott Walker, a Galveston native, wrote the book and says he’s been working on it since 2005. It started as a photography project by Peter Beste, and the two published earlier versions of the book in 2013 and 2014. Since then, they kept collecting material to add to this new edition.

“Basically, I just never stopped,” Walker says.”We were able to stuff a lot more into what we were doing.”

Walker says his project started before a wave of Houston artists hit the mainstream music industry. He says that was an advantage because he and Beste were able to build relationships with these artists before they got famous and busy.

“We just went backwards through the history from that point, so we kinda got to see everything happen. It was really a watershed moment,” Walker says. “Our interest was in telling the history so it was nice to be able to have that sort of timeline to work with.”

Houston’s rap scene got big, in part because the city is so large – it’s the largest city in the South. It’s also incredibly diverse and attracts people from all over the world, Walker says.

“It’s a very fertile, rich, cultural city, as people in Houston, themselves know,” Walker says.

But he says for a long time, people in the mainstream rap scene overlooked Houston. As a result, Walker says Houston rappers “fended for themselves,” making their own records, releasing them on their own labels and creating their own scene.

“I think any time something as fertile like that – and there’s just lots and lots of artists making records – it always provides an interesting area in which to, sort of, micro-focus,” Walker says.

Walker got to know Houston rappers, first, by listening to lots of rap music. He says he and Beste would also bring samples of their work to show people when they’d go to do interview and take photos.

“We would try to be as transparent as we could,” Walker says. “Being a couple white guys coming into the neighborhood, we felt very welcomed and we felt very lucky to be there.”

Houston rappers like Pall Wall and Bun B are well-known, but Walker also interviewed other rappers who didn’t achieve as much fame, and Walker says those artists were some of the most interesting to interview.

“A lot of people that I interview in the book haven’t ever really been interviewed before,” Walker says. “They might be artists that people know from here or there … [but] have you ever heard their story?”

Well-known artists who have been interviewed many dozens of times won’t necessarily open up during interviews because Walker says they know “the game.” But he says lesser-known artists were sometimes more willing to tell their stories.

“They were really enthusiastic about it and they really opened up,” Walker says.

He says in some cases, they opened up so much that he had to call them after the interview to make sure they were okay with Walker publishing certain anecdotes he thought might be too personal.

“They said ‘Oh yeah, hell yeah, I’ve been waiting to do that interview for a long time,'” Walker says.

Houston rap is not homogenous; the city has a north-south division, and rap has also changed over the decades. But Walker says the thing that unifies Houston rap is the label Rap-A-Lot Records, which was founded in the mid-’80s. It wasn’t the first label in Houston that released rap albums, Walker says, but it was the city’s first label to focus exclusively on the genre.

“The way that James Prince structured his label proved inspiring for generations to follow,” Walker says. “People that had nothing to do with Rap-A-Lot … still kinda looked to him and said ‘Okay, well this is the way you can do it, you can make a record label and you can keep it here in town, and you can do things your own way.'”

Walker says Rap-A-Lot still releases records today and James Prince just wrote a book this year.

“That’s certainly a constant thread that everybody in Houston is aware of and I would say inspired by,” Walker says.

Written by Caroline Covington.