From Texas Public Radio:

On May 5, 1986, an 18-year-old high school student disappeared from a tiny town north of Tyler. A day later, her body was found. Suzanne Harrison had been raped and strangled to death.

Jerry McFadden, who had already been jailed then paroled for three rapes, would soon lead police on what was then known as Texas’s largest manhunt before being caught, tried, convicted and sent to death row.

While all this was happening, up in Portland, Oregon, the investigation into the 1979 murder of another young woman – 20-year-old Anna Marie Hlavka – had gone cold … until last week. It turns out Jerry McFadden killed her, too.

“They would never have solved this crime without genetic genealogy. They had absolutely no reason to tie him to the crime. How would they have guessed a Texas killer was in the Pacific Northwest?” says CeCe Moore, chief genetic genealogist at Parabon NanoLabs, a company that uses genetic genealogy to help law enforcement solve crimes.

Moore says genetic genealogy is especially useful when investigators are relying mainly on crime-scene DNA.

“When you don’t have any eyewitnesses, all you have is this genetic witness,” Moore says.

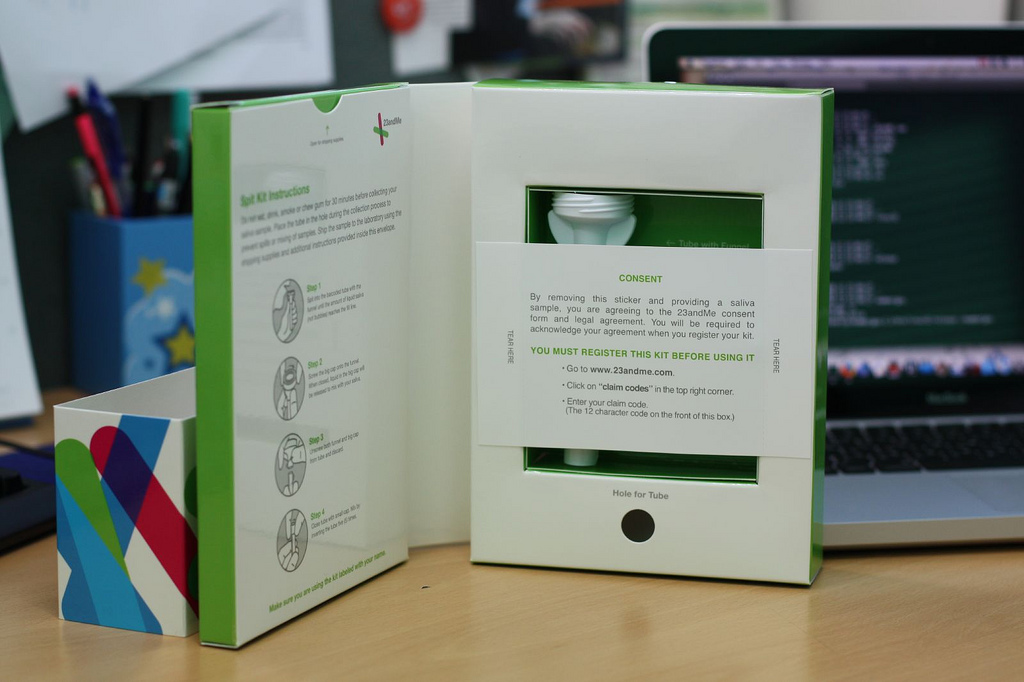

Portland investigators sent their crime scene DNA samples to Parabon’s lab where the company analyzed it and then uploaded to a public genealogy website called gedmatch.com. People with profiles on the website have already been tested through a consumer testing company like 23andMe or AncestryDNA, and have sought out GEDmatch so they can do additional research.

“So, we’re not using the DNA directly from the DNA-testing companies. We’re only using the DNA where people have chosen to upload to that website, and then that crime-scene DNA is compared to everyone in that database,” Moore says.

So they still don’t know who that DNA belongs to, but now the genealogists know to whom the suspect is related. And the amount of shared DNA they find will indicate to the genealogists how closely they are related, and who their most recent common ancestor might to be.

“If you have a third cousin, as we did in this case, then they would be second great-grandparents, so you’ve got to build that person’s family tree back to second great-grandparents,” Moore says. “And then do what I call ‘reverse genealogy’ where you’re trying to find the descendants of all those ancestors, looking for one who was in the right place and the right time to be that suspect.”

The right place was a problem in this case. Family-tree-building led the genealogy team to Jerry McFadden, but as far as the team knew, McFadden lived, killed others and died solely in Texas. So Portland police investigating Hlavka’s unsolved murder did some interviews and discovered that McFadden had, in fact, visited Portland in 1979.

But this case, like any genetic genealogy case, wasn’t solved until police had a DNA match to someone closely related to McFadden. So Portland police hit the road to visit McFadden’s relatives.

“They did travel down to Texas, meet with his family, and the family was willing to provide DNA samples. So that’s how they were able to confirm it,” Moore says.

McFadden died by lethal injection in 1999, and so he can’t be prosecuted for killing Anna Marie Hlavka. But Hlavka’s relatives finally know who killed her, and they also know who to thank: dedicated investigators, creative scientists, genealogists and, perhaps most of all, the “genetic witness”: DNA.