By the 1940s, over 120 Texas school districts had segregated schools for Latino children.

“They didn’t openly tell you the truth… that is, we don’t want Mexican kids sitting next to Anglo kids,” historian Ricardo Romo said.

Instead, proponents for separation pointed what they said were the students’ deficiencies in the English language. And to overall intelligence.

“The majority of schools around the country pretty much accepted that there were people with high intelligence and then there were people with low intelligence. And among the people with low intelligence, as they call it, were Mexican Americans and American Indians,” Romo said.

Romo, the former president of the University of Texas at San Antonio, has studied the life of George I. Sánchez. He says Sánchez challenged the use of IQ tests conducted in English to justify the intelligence argument.

“Whether it was Japanese, Navajo, Spanish, it didn’t make any sense and it seemed shocking to me when I read that. How, can anybody think that you could actually test intelligence… [using a test written] in a foreign language, it just doesn’t make sense,” Romo said.

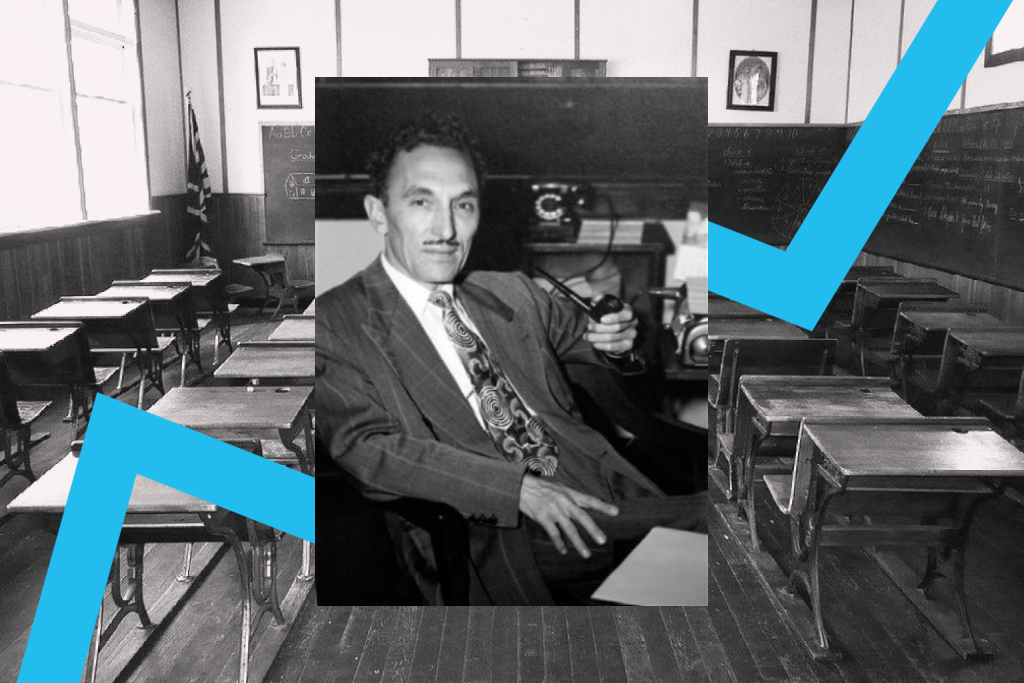

Sánchez was an educator himself and would become known as the father of bilingual education.

George I. Sánchez was born in Albuquerque in 1906. He did well in school and, after graduation, began on his path towards teaching. He earned a bachelor’s degree in New Mexico, his master’s at UT-Austin, and then his doctorate in education from UC-Berkeley. At the time he earned his final degree in 1934, there were only a handful of Latino academics across the country.

“George I. Sánchez was one of the leading scholars in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s in education,” Romo said.

Sánchez saw the inequities of school systems in New Mexico and Texas. He found that rural schools got little funding and offered very little to Spanish-speaking students.

“He was one of the few that questioned it. Everybody just took it, accepted it,” Romo said.

Word War II shined new light on the issue. When the demand for fighting men meant getting non-English speaking Latinos into uniform, it became clear speaking Spanish did not equate with a deficiency.

“Many of them were stronger in Spanish than in English, and were tested differently and they thought, ‘this guy is intelligent,’” Romo said.

But there was still work to be done.

Sánchez (far left) at a demonstration at the Texas Capitol.

In 1940, Sánchez left New Mexico to become a professor of Latin American studies at UT-Austin. His fight for equal educational opportunities for Mexican American children flourished.

“He fought against segregated schools, which were many… many across the state up until the 60s,” Romo said. “And those are the things that he saw as unfair, illogical, not good for how we prepare our Latino students to be leaders.”

Sánchez worked with Mexican American organizations to challenge discrimination through the courts. Some of the early cases of school desegregation were fought in California and in Texas. Still, Texas continued to argue that the Spanish-speaking children needed separate schools.

In 1941, Sánchez served as national president of LULAC. A decade later, he founded the American Council of Spanish Speaking People, a civil rights organization which funded litigation involving discrimination against Mexican Americans.

“His whole plan was to create an organization that would fight for the justice,” Romo said.

Sánchez also served as an expert witness in many legal cases involving Latinos.

“He had been a lifelong absolute champion for Mexican Americans and someone you could count on to be in the battle for equal treatment,” Romo said.

Sánchez died in 1972. But he had a lasting influence on his students and the educational landscape. In 1995, UT-Austin named its education building in his honor.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Voces Oral History Center at UT Austin’s Moody College of Communication as part of Texas Standard’s recognition of Hispanic Heritage Month.