This term, the U.S. Supreme Court will decide three cases on partisan gerrymandering, including one from Texas. At issue, is drawing congressional districts to favor one political party over another unconstitutional?

Grady lives in Cedar Falls, Texas. He recently returned home after several years teaching abroad. To fill his time, Grady decided to get more involved in politics. That’s when he started learning about gerrymandering in Texas. And what he saw bothered him.

“You would think, at first blush, people would say, ‘Well, that’s just not the way a system ought to work, a fair system, you know, that you can just go and pick the people that you want to be in your district so that you can get reelected,’” he says.

So Grady asked us, “What can we as citizens do to address the problem of gerrymandering?”

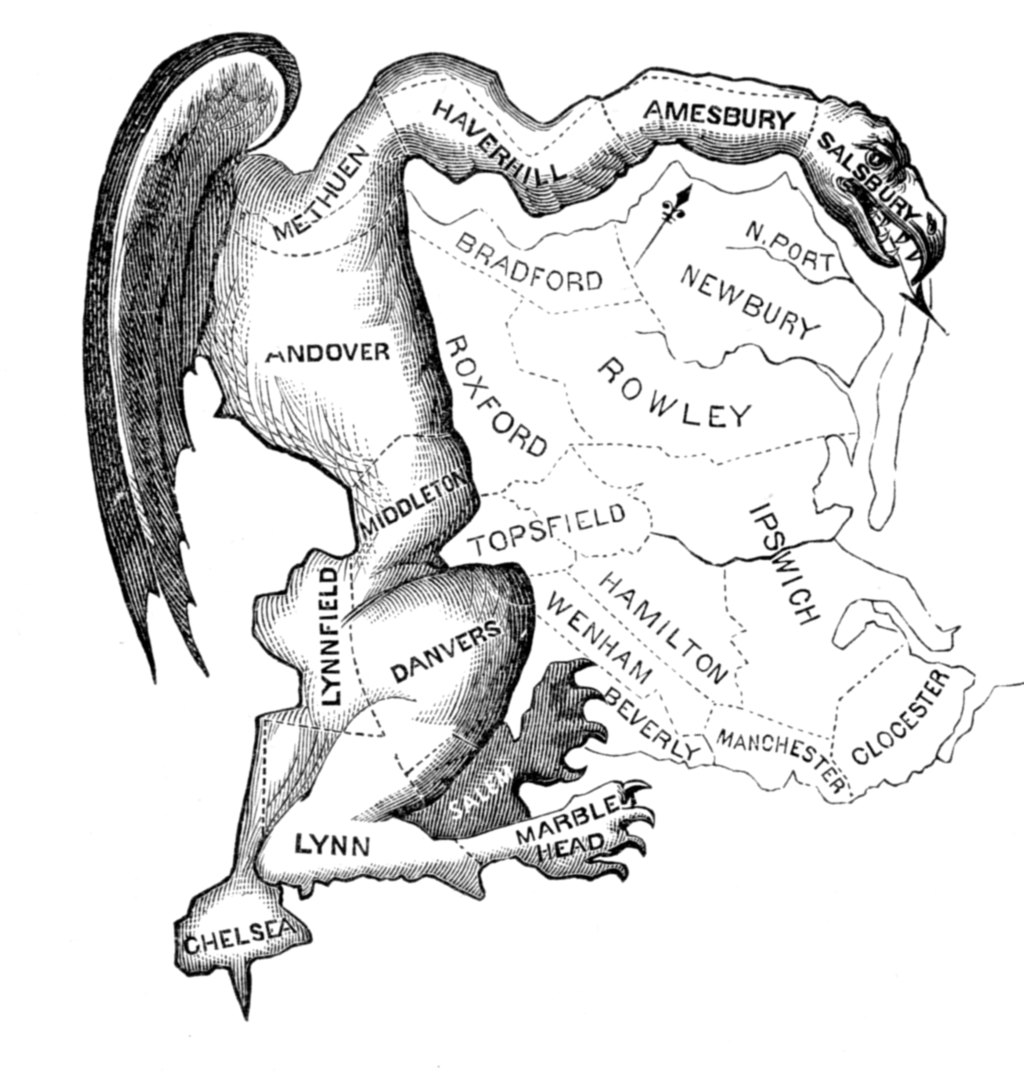

Gerrymandering itself is almost as old as the republic. But for the first 200 years, it was more art than science. Drawing districts involved a lot of guesswork about where a party’s supporters live. Guess wrong, and you spread your support too thin. A small swing of the vote could sweep you out of power. But technology has made it more accurate.

“The computer modeling has gotten so much better with respect to the ability to be able to draw these districts so precisely that they become safe seats,” says Charles “Rocky” Rhodes, a constitutional law professor at South Texas College of Law Houston. Rhodes says that’s a major reason the Supreme Court is finally taking up the question.

“Even in a gerrymandered district,” says Rhodes, “in order for the courts to be able to review whether perhaps the gerrymander is somehow unconstitutional, it helps to see what has been the impact of the gerrymander on individual voting rights.”

As an example, Rhodes points to North Carolina. In 2016, just over half of the voters there chose Republicans. But North Carolina ended up electing 10 Republican congressmen and just three Democrats.

Still, even if the justices impose limits on gerrymandering, that may not make new districts much more competitive.

“Even without gerrymandering, there’s just a natural geographic sorting,” says Elizabeth Simas, a political scientist at the University of Houston who studies electoral behavior. “There was a great map recently that showed Texas divided by counties and partisan competition within counties. And it’s really not competitive. Counties tend to be either red or blue. They’re not subject to the same kind of manipulation that our House districts are.”

If your party happens to be in the minority, there’s a natural tendency to look at political maps and get discouraged. Cal Jillson, a political scientist at Southern Methodist University, says that’s a mistake. He says the first thing citizens can do to address the problem of gerrymandering is to show up to vote.

“Elections are contests of strength between the two major political parties,” says Jillson. “So if you’re a Democrat in a Republican district, you’ve got to get out there and work to keep your Democratic ticket competitive. If you’re a Republican in a Democratic urban district, for example, you’ve got to show the flag as well and get out there.”

The second thing citizens can do is run for office. Gerrymandering may make it tougher for one party to win a given seat in Congress. But the odds drop to zero if the party doesn’t put someone on the ballot.

Simas says that happens all too often. “In Texas we see a lot of just noncompetitive races, noncompetitive in the sense that they don’t have a viable challenger to the opposition,” she notes. “Candidates are the ones ultimately who can inspire people to go out and give them that glimmer of hope.”

That theory will get a test this fall. Of the state’s 36 congressional districts, 32 will have candidates from both major political parties.