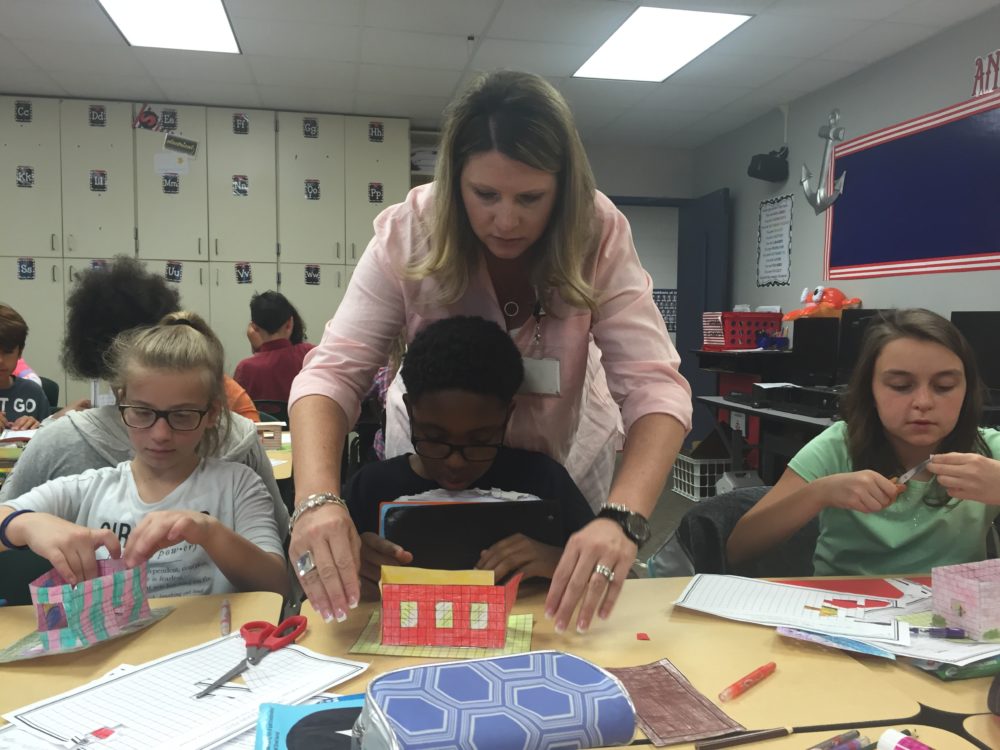

At Timbers Elementary, fifth graders recently cut pieces of paper and taped them together to create tiny houses. Their teacher Stacey Ward checked on the next step.

“If I’m looking at the bathroom sink, each one of these sides of the square is one, right? So tell me how you’d find the perimeter of the bathroom sink,” Ward asked one student.

This craft activity was really math practice in disguise. It’s one reason why her students say Ward makes math and science fun. She’s taught for 20 years, mostly in the Humble Independent School District, a suburb northeast of Houston.

Like many teachers, Ward has watched the 85th Legislature session with a sense of resignation.

This session in Austin, state lawmakers have debated a slew of high profile changes to public schools. There’s been a so-far failed attempt to create vouchers, which would send public tax dollars to private schools; changes to the state’s A- F report cards to grade schools and districts; and the state budget.

“When they took $5.4 billion from us … we kind of learned to do without what we had, so it’s kind of the new normal if you will,” she says.

But Ward sees a bright spot for her students and other teachers from her own state representative, Dan Huberty. The Humble Republican chairs the public education committee in the Texas House of Representatives.

“It’s my pleasure to be joined by a bipartisan group of my house colleagues, school board members, educators and charter school officials to introduce House Bill 21,” Huberty announced at a press conference in March.

The bill tries to reboot how Texas pays for public schools – a conundrum that has stumped lawmakers for decades.

“This legislation will put $1.6 billion new into the public education sector,” Huberty told reporters.

To put that increase into perspective, the House has budgeted about $42 billion for public schools over the next two years.

The House approved Huberty’s bill, and if it ends up passing the Senate, it’ll boost the basic budget for every student by about $200. The bill also creates new funding for dyslexic students. And, for the first time since the 1980s, ups money for bilingual education.

That’s a good step, but not enough, according to Ivan Castillo, who’s been teaching bilingual grade schoolers for 22 years.

Castillo immigrated to Texas from Mexico as a kid, when there was no bilingual education. Now, after 30-plus years of flat funding, English learners might get a 1 percent increase, or about $50 per student.

“They need to go into the schools and see what are the things that we have, what are the things that we need,” Castillo says.

For Castillo, that’s more books in Spanish, something his school can’t always afford.

“It also makes me angry because I know that we have the money in the state and the government in Austin is not doing enough to give us the funds that we need here in Texas,” he says.

Talk to even more teachers and education advocates, and they’ll say Texas legislators are shortchanging other areas, like higher education.

Others, like Lonnie Hollingsworth, general counsel for the Texas Classroom Teachers Association believe lawmakers are right to focus on K-12 this session.

“Hopefully we’ll be looking at additional funding for public schools. That’s a good thing,” Hollingsworth says,

Hollingsworth hopes more measures will pass the finish line.

“The continuation of health insurance for retired teachers,” he says. “That’s also a good thing. Potential reduction on the reliance of high stakes testing, also a good thing.”

But then, according to several teachers Houston Public Media talked with, there’s the list of things lawmakers are forgetting: plans to upgrade technology in classrooms; ways to keep good instructors on the job; and how Texas will manage a rapidly growing number of students.

Cory Colby teaches at Lone Star College and is the past president of the Association of Texas Professional Educators. He says that after the cuts in 2011, more funding sounds great, but lawmakers need to consider quality.

“We are adding basically a Fort Worth ISD to the system every year. I believe the number is 50,000,” he says.

“You have to ask the question,”Colby says ” what kind of education do you want to give your students? Do you want to give them an education where they’re receiving minimal support?”

He says that lawmakers need to think bigger next session, not just about keeping up.