Recent world events seem so complicated – and perhaps intractable – that some citizens may reel from a sense of hopelessness. But maybe our collective memory fails us – it’s easy to forget how much the world can change in just a matter of days.

In less than two weeks in 1978, a world-changing event not only ended one of the most bitter conflict in modern history (or at least a part of it), with effects that endure to this day.

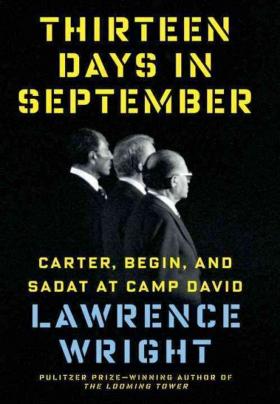

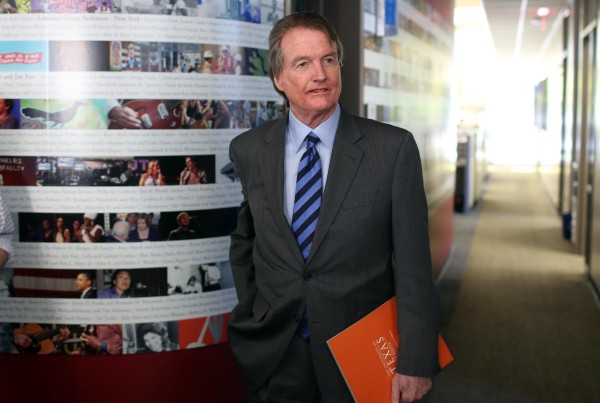

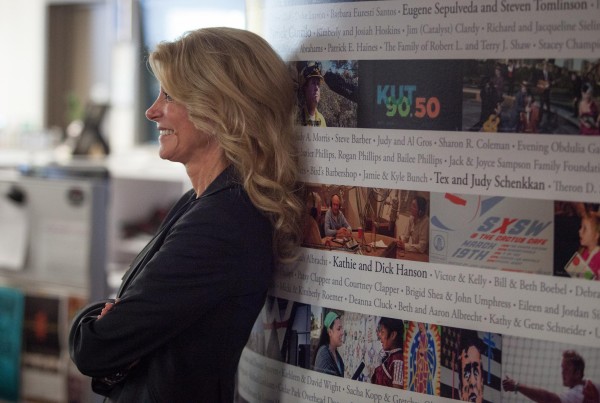

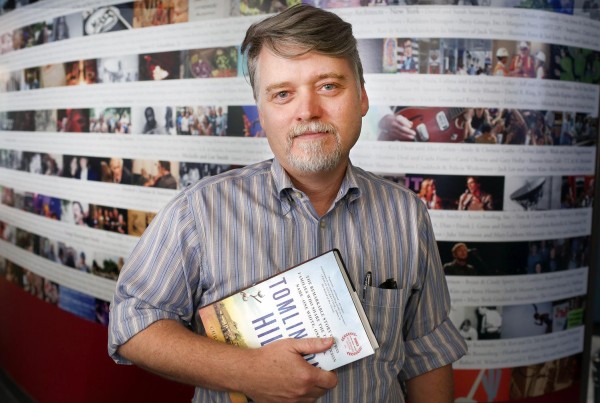

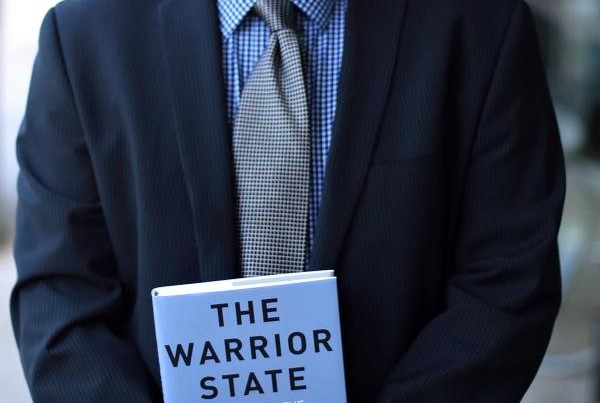

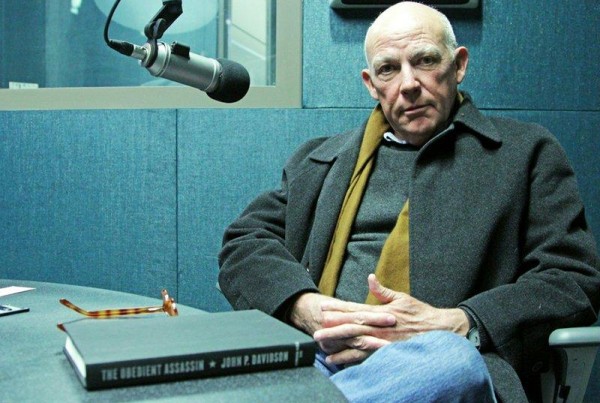

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Lawrence Wright speaks with Texas Standard’s David Brown about his new book, “Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin and Sadat at Camp David,” a detailed account of the Camp David accords between Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin. Facilitated by U.S. President Jimmy Carter, the agreement brought peace between Egypt and Israel.

Wright will be speaking at the Texas Book Festival on October 26. He became fascinated by Middle Eastern conflict while living in Egypt.

“The idea that the Middle East is eternally committed to conflict is something that many people believe – and yet apparently not,” he says. “It is possible to bring peace in the Middle East. I was intrigued by [the question of] how did this success ever occur in a region where peace is such a remote possibility.”

Wright acknowledges that the idea for holding a conference at Camp David, a Maryland presidential retreat, was due to First Lady Rosalynn Carter’s ingenuity. Her presence at the conference was central to its success.

“It was her idea,” Wright says. “Carter was despairing about the drift of events in the Middle East and he wanted to do something about it. He had an idea that there would be some international summit in Geneva, which was going to go nowhere. Rosalynn said, ‘Why don’t you bring them here [to Camp David]? … Get them alone and away from the press.’ He immediately saw that as a great idea.”

The remote location allowed the leaders to escape outside influences and delve into the deep issues at hand. “The isolation was important,” Wright says. “Isolation also created a kind of pressure to come to an agreement.”

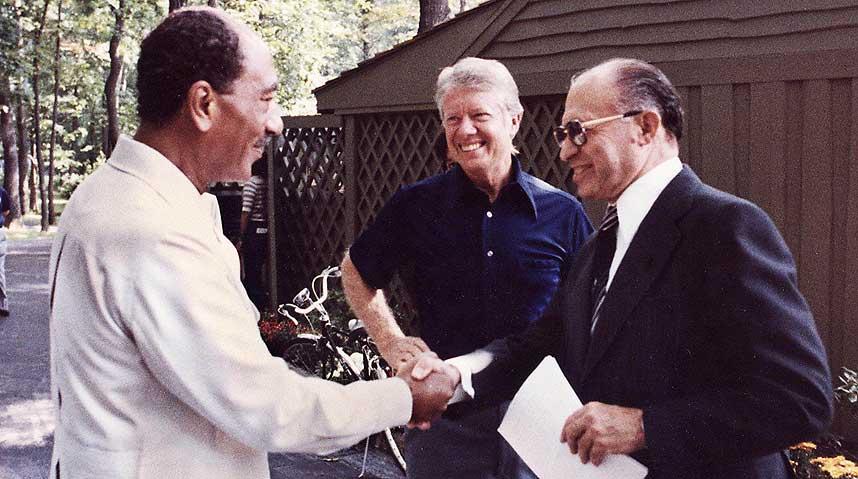

Presidents Sadat, Carter and Prime Minister Begin meet on the Aspen Cabin patio at Camp David in this White House staff photo.

Credit Bill Fitzpatrick

Initially the conference stalled, with Begin and Sadat arguing and incapable of being with one another in the same room. But, as Wright says, Carter knew how to find common ground.

“One day, the sixth day of Camp David, he decided to take a risk and take them to Gettysburg, which was nearby, and show them the battle field. [Carter] had an ancestor who… walked home to Georgia after the war and saw the devastation. I think that it made a real difference in the mentality of Sadat and Begin when they saw that Carter understood the cost of war,” Wright said.

Carter had to put U.S. prestige on the line to create a lasting and impactful document between Egypt and Israel. But Wright says that action was necessary to the success of the conference.

“There hasn’t been a single violation in 35 years between Egypt and Israel… It would never have happened if Carter hadn’t done that,” Wright says. “[Carter] had to be the one to force it. Both sides wanted to make peace but they couldn’t make peace with each other. He helped them make peace with the United States, in a way, because he was saying, ‘If you don’t come to an agreement here, your relationship with [the U.S.] is going to suffer.'”

In his assessment of Carter’s role at Camp David, Wright says the president is worthy of praise, regardless of his popularity as president at the time.

“Carter deserves credit for what he accomplished at Camp David … In his frailties and in his virtues he was the same. For instance, he was a micromanager and this was a problem with him. It was hard for him to prioritize things as president – but that quality of micromanaging was absolutely essential at Camp David.”

Despite current events, Wright has not lost hope for achieving peace in the Middle East. While he asserts the status quo would like the conflict to continue, he says the price is too high.

“I think there are two tropes that we should take out of our current discussion. One, that there are perfect partners for peace… Could you cast a less likely team of people to bring peace to the Middle East? I think not. But they did it. What they did have in common was political courage, in great amounts, and that is why they were able to achieve what they did.”

“The other [trope] is timing. You always hear ‘it’s not the right time.’ Well, this was at a time in 1977 [when]… the world was in flames – as it always is. So there is always a time to make peace – it just takes the commitment of the leaders and the political courage to do so.”