In a piece in The New York Times, chief White House correspondent Peter Baker sent a dispatch from Dallas – where the 43rd president of the United States leads a life of self-imposed exile.

While his vice president, Dick Cheney, continues to wage war on Democrats, George W. Bush stays out of the public debate.

That might line up with what you’d expect, if your idea of the Bush-Cheney years was one of the vice president as Darth Vader – the power behind the throne controlling Bush’s hand.

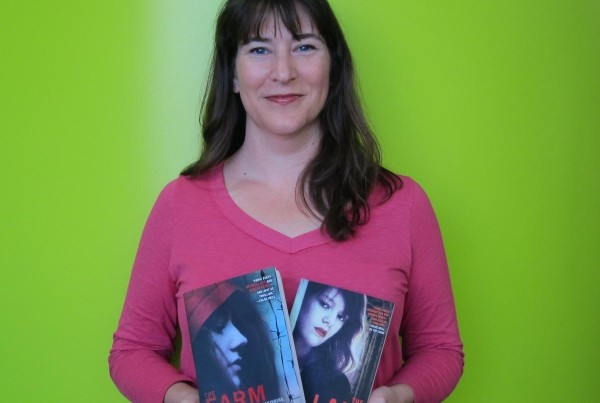

But in his a revealing new book “Days of Fire,” Baker says the story of Cheney as puppet master is hard to nail down.

“Like a lot of myths, it has some grounding in truth – and the truth was Bush did invest in Cheney extraordinary authority and autonomy,” Baker says in a studio interview with KUT’s David Brown.

“Cheney was a seasoned figure who provided a lot of guidance to someone who didn’t have a national security background, particularly on 9/11. But then it became easy to exaggerate and the late night comics enjoy a good running gag. Over time it became a conventional wisdom that set in like concrete.”

Baker says he wrote this book to primarily explore the unique relationship between Bush and Cheney.

“I covered the Bush White House, and, like a lot of people, felt Cheney was an important and powerful figure. But I didn’t really know exactly how. It was always a mystery to us.”

Baker describes Cheney as “the most influential vice president in history.” He called him the most dominant of all of Bush’s advisers, someone who’d managed to circumvent rivals such as Colin Powell or Condoleezza Rice. Cheney would be in meetings and wouldn’t speak up unless the president asked him to say something. Yet, other aides recognized that he would stay back after everyone left.

Over time though, Cheney’s influence waned. In the last days of the Bush administration, Bush and Cheney were on opposite sides of a lot of important issues, including North Korea, climate change and gun legislation.

The last disagreement came in the form of a pardon for Cheney’s chief of staff Scooter Libby. When Bush decided not to grant him a pardon for perjury and obstruction of justice, Cheney told him he was “leaving a good man wounded on the field of battle.”

While conducting research for his book, Baker noticed a common theme in each interview.

“Cheney was pushing on an open door,” Baker says. “He wasn’t convincing Bush to do something he didn’t want to do, but guiding Bush in a direction he was already inclined to do. I did 400 interviews with 275 different people, and not one person had said Bush had told them he’d been convinced to do something he didn’t want to do.”

“Days of Fire” is on bookshelves now.

This post was prepared with assistance from Fauzeya Rahman