From KUT:

Austin radio icon John Aielli, whose fearless and improvisational approach delighted and polarized listeners for over 50 years, died Sunday at 76.

“He was such a joy to work with, and so important to what the stations have become,” KUT/X General Manager Debbie Hiott said in a message to staff.

“John was an Austin treasure and was an indelible part of so many lives here in Austin,” Matt Reilly, KUTX program director, said in a statement. “His unique perspective on the world made being with John a joy. Our lives are less interesting with him gone.”

Aielli’s passing silences one of the truly unique voices in American broadcasting.

A life in music

From the very start, Aielli seemed destined for a life in music. His dad was a pianist and his mom sang in a jazz band.

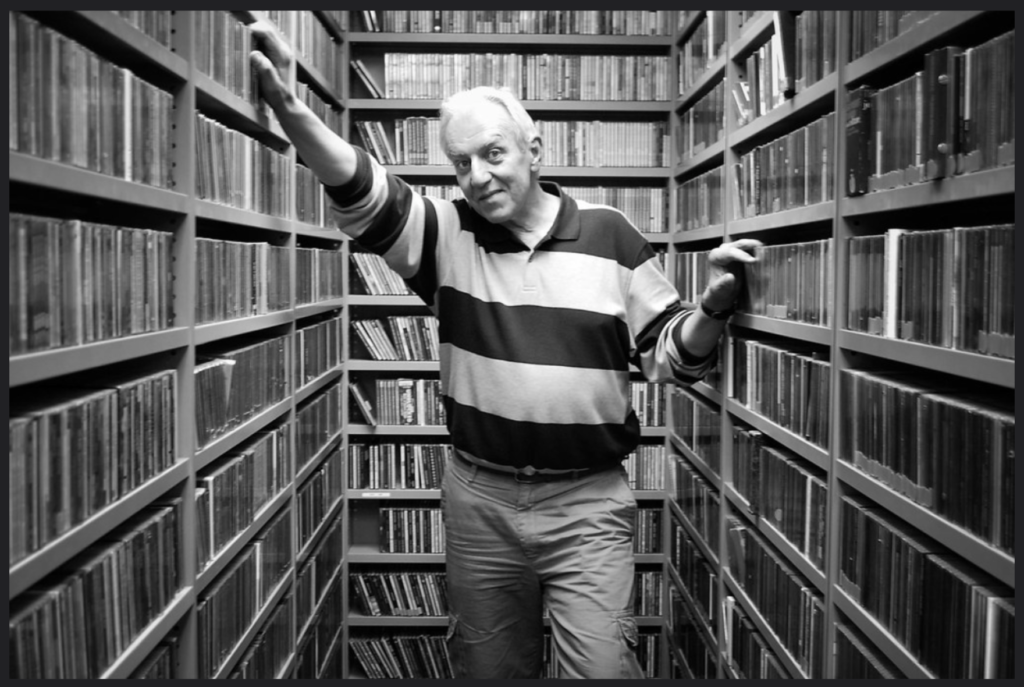

Aielli, seen here in 1972, wanted to “soften up the austere, elitism of classical music” by mixing it up with other genres.

He was born in Cincinnati in 1946, but the family moved to Killeen, near his mother’s family, when he was 8. There, Aielli sang in his school choir and studied piano. At 17, he got a piano scholarship to UT Austin. But it only covered tuition, so he put off school and worked a few years as an announcer at the Killeen radio station KLEN to save up money. That’s how John Aielli became the man who alerted the city of Killeen to JFK’s assassination.

Arriving at UT in 1966, Aielli parlayed his broadcasting background into a job at KUT, then an eight-year-old public station known as “The Longhorn Radio Network.” He was a 20-year-old student who spun music on the side.

Aielli loved classical, but his musical curiosity was irrepressible. He started adding different genres to the rotation: folk, world music — whatever struck his fancy.

Decades later, he said he hoped mixing different types of music would introduce more people to classical and “soften up the austere, elitism of classical music.”

For the same reason, he went through a phase of wearing overalls to classical music performances.

Eklektikos is born

By 1970, Aielli’s show was named Eklektikos in honor of its wild mashup of musical genres and interviews. It was this formula (or, lack of one) that lasted for more than 50 years.

Beyond playing music, Aielli interviewed countless musicians, writers and artists.

His long, meandering talks with guests (and without them) became a trademark of the show. In the early days, though, it may have been borne of necessity.

“Back when I arrived at KUT, John was on six hours a day,” says Jeff McCord, now a music editor and host at KUTX. “In those days we were running in the [music library] and finding CDs to play and running back. And you got tired of doing that. If a person was at all interesting he would talk to them for a long time.”

Aielli himself described his job as that of “facilitator,” someone who connects his audience with the cultural life of Austin. And, as his following grew, so did his role in that cultural life.

Aielli, who dreamed of one day becoming a singer, says he became a DJ “by default.”

Radio host by default

While he was often in the audience at plays and concerts, Aielli had musical ambitions of his own. Through the ’70s, he trained as a vocalist and gave annual recitals. In the stairwell of the former KUT studios, his haunting vocal scales would reverberate every day up the floors of the building. His Holiday Sing-Along at the Texas Capitol became a tradition cherished by generations of Austinites.

For decades, he dreamed of moving to New York to pursue a singing career. But by the time he was confident enough with his skills in the early ’80s, he said, he felt he was too old to start a new career.

Aielli holds a microphone up to a young singer during the Holiday Sing-Along at the state Capitol in 2017.

He said giving up on that dream may have been one of his best decisions.

“I wound up by default doing something that I really, really love,” he told The Daily Texan. “I get to be in the world of music playing records and talking to musicians. I can’t be happier than that.”

‘Utterly unafraid’

The truth is, music and guests were not what made Eklektikos the decade-spanning phenomena it became. The show was about Aielli himself. He did things you don’t hear on the radio. He could have an author in to talk about a new book, but decide they should discuss gardening instead. He’d break into the middle of a song to comment on it. He let dead air take over for long stretches of time.

Aielli broke “every rule of broadcasting that there is,” McCord said. He refused to wear headphones (one reason for that dead air) and didn’t prepare for interviews. It led to moments that were either laughter- or cringe-inducing, depending on the listener, McCord said, like the time Aielli “somehow confused Bono with Sonny Bono.”

It never fazed John.

“He was just utterly unafraid.” McCord said. “When the Titanic movie came out, he would not stop playing that soundtrack. He quite often would play a song three or four times in a row if he really loved it. You know who does that on the radio? No one.”

“Eventually we just had to hide the CD,” he said.

Aielli had a stream-of-consciousness style of presenting. He would free-associate words and themes to determine what to play or talk about, and it could feel improvised and chaotic. But the chaos was integral to the magic he created.

“If there’s no dead air, that means you have to be prepared in advance for every single thing,” Aielli once told his hometown newspaper, the Killeen Daily Herald. “I like to fly by the seat of my pants.”

Destined to be an icon

For a lot of people, discovering Eklektikos was a weird welcome to a city with a reputation for weirdness, a rite of passage that touched generations.

“What I love most about Austin is the friendliness,” Aielli once said. “There are good people here, and it spreads to the people who come here.”

Those close to him felt that kindness along with the weirdness.

“He could be very generous,” said Jay Trachtenberg, a longtime friend and colleague of Aielli’s.

At the radio station, Aielli would bring in thrift-store finds and homegrown tomatoes to share with co-workers. He kept chocolates at his desk to pass around and was quick with a compliment for anyone trying on a new outfit or hairstyle.

But, much like his on-air presence, he could also frustrate.

“John lives in his own world and he sometimes isn’t aware of what’s going on around him,” Trachtenberg said. “Sometimes we’d go at it to the amusement of our co-workers. We’d be like the odd couple bickering.”

Jay Trachtenberg (left) says sometimes he and Aielli would bicker like the odd couple.

The station is full of stories about Aielli, like the time a worker walked into Studio 1A at night to find him standing on his head in the pitch dark, Trachtenberg recalled. “Then John being upset because he was interrupted!”

Aielli lived alone, but loved to be around people. He’d often share stories of his friends on his show. In his free time, he spent hours at his regular table at Cherrywood Coffeehouse, reading a book or chatting with strangers.

He was “a really sweet guy,” Trachtenberg said.

The work of some innovators can appear less groundbreaking with age. As time passes, what made them special becomes commonplace. But the opposite was true of Aielli. As broadcasting conventions became less free-form — what McCord calls “tighter” — Eklektikos seemed weirder by comparison. In a city that prides itself on weirdness, Aielli was destined to be an icon.

“I lucked out,” Aielli once said of the twists of fate that brought him to a half-century in radio. But, of course, so did we.

There used to be a bumper sticker you’d see around town that summed up Aielli’s affectionate and complicated relationship with his audience. It said: “If You Don’t Teach Your Kids About John Aielli, Who Will?”

The answer is: thousands of his fans and friends. Without him, radio will never be the same.