From KUT:

What’s in a name? Well, a lot – at least for those in Austin’s vibrant restaurant, live music and condiment scenes.

Earlier this month, Stubb’s Austin Restaurant Co. settled a trademark dispute with McCormick and Co., and its subsidiary One World Foods, so that McCormick will be the only company that can use the name Stubb’s.

So now, the Maryland spice company that owns the Austin sauce company is no longer allowing the Austin barbecue spot and music venue to use the nickname of the man that opened the restaurant.

Perhaps anticipating that this might happen, the restaurant Stubb’s filed paperwork to claim the name “Liberty Lunch,” sending a collective record skip that could be heard all the way to Antone’s – the record store, not the club. (Incidentally, the two Antone’s businesses are owned by different companies.)

Stubb’s registering the name Liberty Lunch raised several questions like, “Can they do that?” and “Will the new brand stick?”

“A brand is like a handshake. It’s a promise,” says Mitch Baranowski, a creative director and branding expert based in New York. “It’s a promise that you’re going to deliver on a certain product, or service, or experience. And these days, what a lot of consumers really want is an authentic brand experience.”

To get that authentic brand experience, he says, you need heritage, sincerity and quality. Stubb’s is losing some of that heritage – its namesake – as a result of the lawsuit.

“C.B. Stubblefield loved music,” Baranowski says. “His original west Texas restaurant was frequented by so many great Texas musicians, from Joe Ely, Tom T. Hall, many others.”

It was in Ely’s house that Stubblefield began to bottle his sauce for sale, according Stubb’s website – the sauce company, not the restaurant.

“They used to jam at his place all the time and that continued when he moved it to Austin,” Baranowski says. “So, the live music component, that part of the brand heritage will be called up when they move over to the new name Liberty Lunch.”

A dive

If that name doesn’t ring a bell, here’s a primer for those of you too young or too new to Austin.

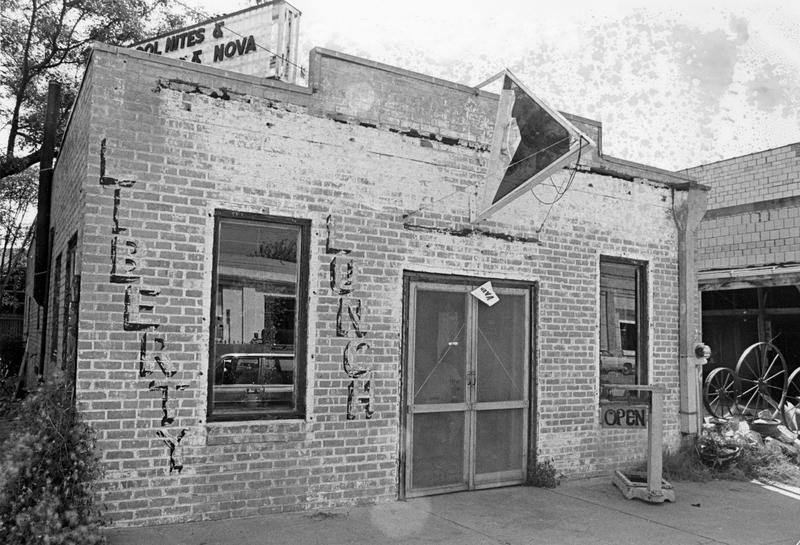

Liberty Lunch was one of the city’s storied live music venues. It hit its stride in the 1980s and 90s, booking a who’s who of music. Located in the middle of what are now high-rises and boutiques, Liberty Lunch thrived without any aesthetics.

“I think that was the beauty of the place,” says KUTX Austin’s Susan Castle, who says she used to go to Liberty Lunch two to three times a week. “It was a dive, a complete dive. It had half a roof on. But they had so many big names come through before they got big.”

“Great music, I mean that’s what it was known for, right?” says Baranowski, who lived in Austin while attending undergrad and graduate school at the University of Texas. “So, you’d go see Michael Johnson and the Killer Bees, or Twang Twang Shock-A-Boom or the Reivers.”

The Reivers were regulars at Liberty Lunch. You may know the band by its original name, Zeitgeist, which it had to change after a lawsuit.

“A lot of those times, back in those college days, we couldn’t quite afford the cover charge, so we might sit out on the curb eating our beans and rice from La Zona Rosa,” Baranowski says. “But as I started working more and more around town, I had the means to pay the hefty $5 to $6 cover. Great sweaty, rocking nights at the Liberty Lunch.”

“You could go right up to the stage and get just washed over [by] the sound of the Funky Meters,” Castle says.

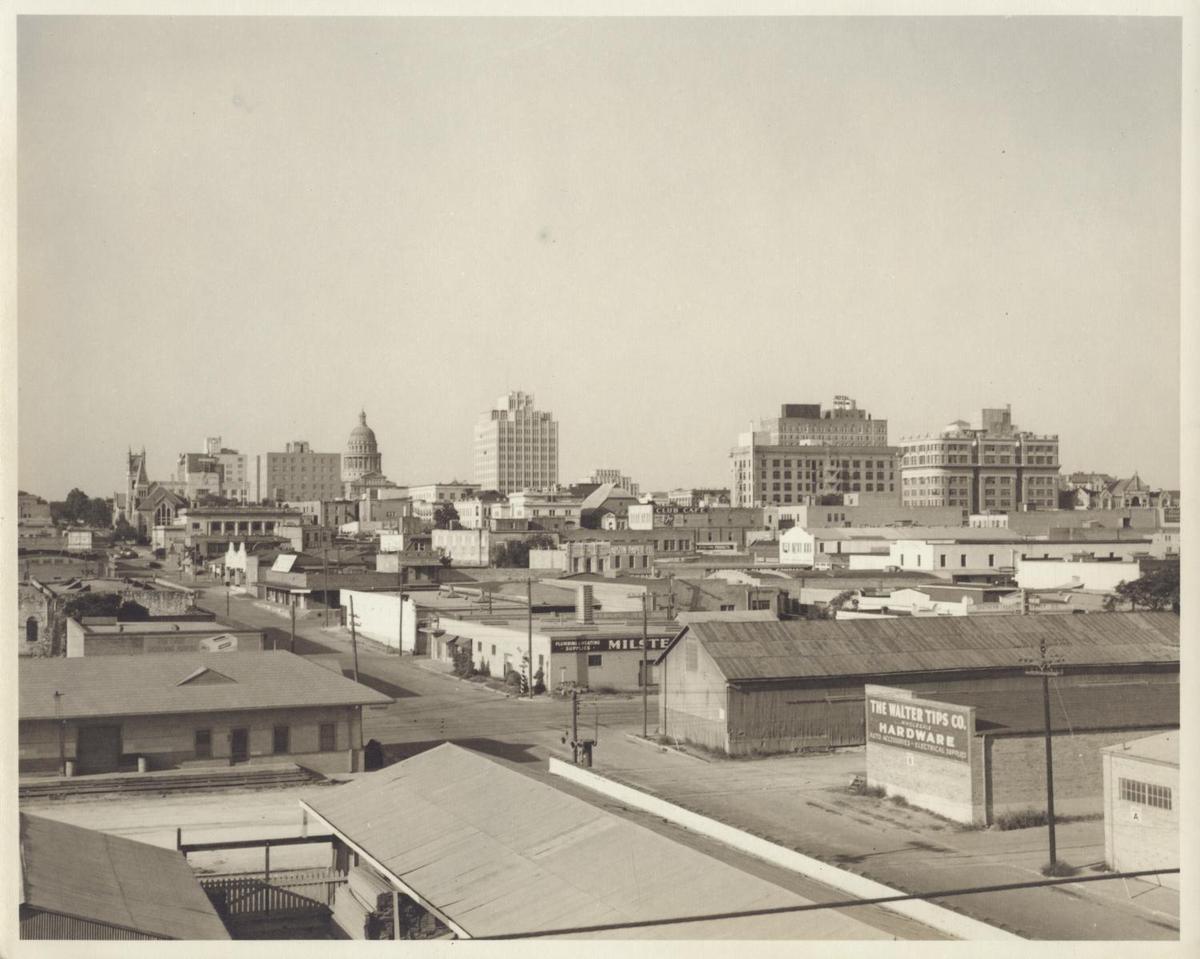

It was one of those places that many who were in Austin at the time remember fondly. It closed in 1999 to make way for the new City Hall and two office buildings.

Liberty Lunch’s last owners, Mark Pratz and Jeanette Ward, were not all that fond of the weird name, according to The Austin Chronicle. And that may make you wonder how it even got the name.

A lumber yard

If you don’t know what the original Liberty Lunch was, here’s a primer for those of you too young or too new to Austin.

The club’s original owners, Shannon Sedwick and Michael Shelton, bought the lease way back in 1975 from a guy who was running an open-air bar.

“[There were] pickled eggs on the counter, with one with a bite taken out of it and put back in. It was just pretty much a dive,” Sedwick says. “It was funky, very, very funky.”

Sedwick and Shelton have had a hand in the development of a number of Austin night spots, most famously Esther’s Follies, which they still own. Back in ’75, they brought music to Liberty Lunch, booking local bands like Beto y Los Fairlanes and The Lotions.

“All the outside was still pretty much the way it had been from the early days when it was a lumber yard,” Sedwick says.

Wait. Lumber yard?

A burger stand

So, if you don’t know what the original, original Liberty Lunch was, here’s a primer for those of you too young or too new.

At one time, Austin’s warehouse district was more than inexpensive real estate to start music clubs; the warehouses were used to house wares.

Calcasieu Lumber was one of – if not the – biggest building suppliers in Austin. If you live in an old home in town, there’s a reasonable chance that there are Calcasieu beams somewhere in the structure.

Supplying lumber and hardware to much of Austin required a lot of warehouse space.

“We had a window department, an appliance store, an architectural mill plant, the main office – these were all in different buildings down there in the Second and Third Street area. But our main office was on Second Street,” says Nick Morris, the former president of Calcasieu. His grandfather Bill Drake started the business.