This story originally appeared on KERA Art & Seek.

Paul Black shows us around the photo lab he opened in 1982. Processing camera film and making prints used to be big business for him. Then the bottom fell out.

“It was dropping at the rate of about 25 percent a year. From 2002 on, it just –people stopped making photographs,” Black says. “They took photographs, but they didn’t hold them in their hand.”

During that time the photo giant Kodak went into bankruptcy. Film seemed to be dying. But at Black’s lab, Photographique in Deep Ellum, there has been a turnaround.

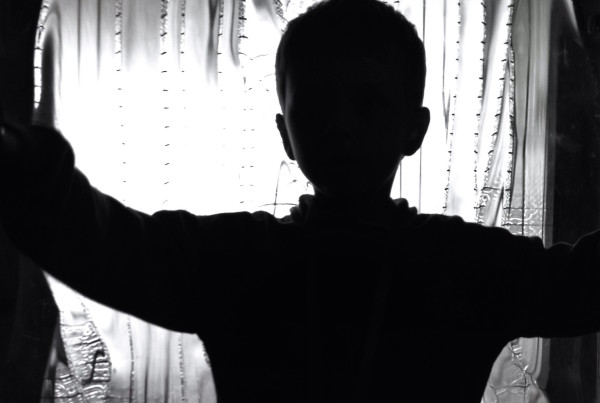

Paul leads us into the darkroom and introduces us to a member of the digital generation making pictures the way it was done since the beginning of photography, with light and chemicals.

By day, Brandon Thibodeaux shoots digital pictures for “The Wall Street Journal” and “The New York Times.” But for his personal work he has taken up old-fashioned film.

“I think there’s a preciousness to it, you know, and there’s a sense of magic, as well – there’s alchemy,” says Thibodeaux. “It’s slow and more methodical and it fits what I’m looking for.”

He’s printing a warm-toned paper so it’s a three-minute development time.

Black explains the printing process that can take hours. It’s not a fast process like an iPhone. But the prints will last 200 years.

There used to be big photographic labs all over Dallas. One went all digital. Another this year stopped processing black and white film. Black kept his business alive by retouching old photos for customers. Now he says his film lab is busier than it’s been in years. So who’s driving this boomlet in film?

“Kids. Brandon,” says Black. “They all have vinyl record players and go to the local vinyl stores here in Deep Ellum. And they take their film pictures and they scan them and they put them on Instagram. They have hashtags like “film is still alive” or whatever. Ask Cassandra, she knows more about it than I do.”

Cassandra Black is Paul’s daughter, who also works at the lab.

“Young kids that are coming in and finding old cameras and shooting film, sometimes for the first time, and they’re loving it. They love to talk about it and the mystery about it, cause everything is so digital and you know so ephemeral. I mean you look at something on your phone and it’s gone.”

Film may have a niche future. The film manufacturer Ilford opened a new U.S. plant and says 30 percent of its customers are under 35.

“Everybody’s so inundated with images they just don’t seem to be worth anything any more,” says Cassandra Black. “So then when they get a print back from a roll that they’ve shot, where you have to slow down and take your time, and shoot a roll, and think about each frame, and how to expose it, and they go ‘Wow, look at what I did,’ you know. And we’re all at the front counter going yeah, isn’t it cool. So we’re all about it.”

“When you put that paper that you’ve exposed to light in the chemical and that image appears, it’s pretty neat,” says Paul Black. “If you haven’t seen it before it’s really exciting. That’s the magic.”

Magic that can last for 200 years.