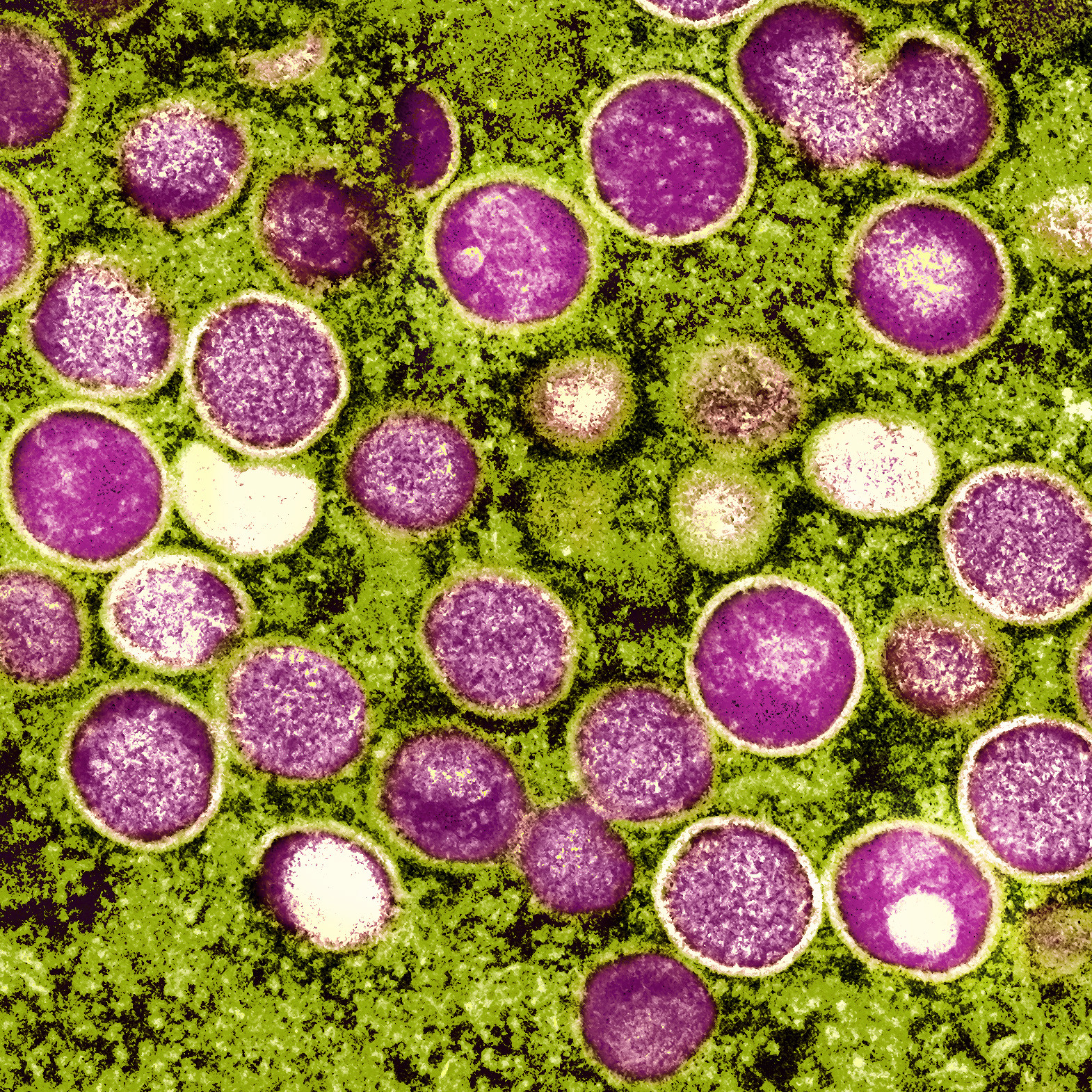

On July 23, the World Health Organization declared monkeypox a public health emergency – its highest alert level, and one rarely given. Officials cited more than 16,000 cases in 75 countries and urged for a coordinated international response.

On Thursday, less than two weeks later, the White House declared a public health emergency in the U.S. over the outbreak, which has infected more than 7,100 Americans.

Though an emergency hasn’t been declared in the state of Texas, as cases begin to rise – there have been about 500 in the state, at least 40% in Dallas County alone – officials are facing questions about public health messaging and how to distribute a very limited supply of vaccines. Jennifer Shuford, the state’s chief epidemiologist, joined Texas Standard to share more about transmission, prevention and vaccines:

What’s the status of vaccine availability?

There is a worldwide shortage of vaccines, Shuford said, with manufacturers trying to manufacture and distribute as quickly as they can. There is not a timeline for when vaccines will be widely available.

“And so, there are limitations on how many vaccines that we can provide. But Texas has been well-represented,” she said. “We’ve been allocated a good amount of vaccines for what’s available. And so far, we still have adequate supplies for that post-exposure prophylaxis and expanded post-exposure prophylaxis, those populations that we’re really aiming to get this vaccine in right now.”

“It’s not going to be enough for us to give a preventive vaccine to everyone who may be at risk. And so, we are trying to target those vaccines for people who are at the very highest risk and using that kind of small allocation of vaccines that we’ve received in the best way that we can to help prevent some of those infections from happening.”

How transmissible is monkeypox?

What’s driving this current outbreak is really close contact, really close skin-to-skin contact in most cases, Shuford said, and there have also been skin lesions associated with these cases. It also can be transmitted through respiratory secretions, like spit, “but it’s usually with people that have kind of prolonged contact with respiratory secretions, say you’re kissing or in really close contact.”

Most transmission is happening once symptoms have already started, Shuford said, “so people can become aware that they’re ill and then they start to get a rash. And those are real indicators to a person that they need to isolate themselves and seek medical attention to find out what’s causing their symptoms.”

“The good news is that we’re not seeing this spread on airplanes. We’re not seeing it spread from people to their health care providers as long as their health care providers are wearing the recommended PPE. And so we’re not seeing that same level of transmission that we were seeing with COVID, where it was just really spreading like crazy. This is a little more contained and takes a little closer contact before it’s transmitted.”

The World Health Organization has said that 99% of the cases involve men who have sex with men. But public health officials, as the New York Times has noted, have struggled with acknowledging that some of these factors could stigmatize gay and bisexual men. At the same time, part of a proper public health response is targeting people most at risk in the riskiest activities. How are you trying to deal with that issue?

Getting that accurate information is important, Shuford said: What we are seeing Texas – similar to what’s being seen across the United States and around the world – is that this is primarily right now in the male population, with over 98% of identified cases people who are assigned male sex at birth. Most of those individuals are men who have sex with men – but there are many populations at risk right now.

“We know that this can easily spread to women and to children as well if they have that same level of close contact with somebody who has monkeypox,” she said, and it’s not “what we classically think of as a sexually transmitted infection, where it just comes from those sexual contact or sexual fluids. This can be just skin-to-skin contact or even respiratory secretions. And so, it really is not limited to [gay or bisexual men]. It’s anyone who has that close a contact with somebody who has monkeypox.”

What do people need to know about protecting themselves from monkeypox?

Shuford said individuals can protect themselves by understanding their surroundings: “Any time that you’re around somebody having skin-to-skin contact with somebody, look at their skin, see if they have any skin lesions. And in cases where you’re in venues, it’s good to leave your clothes on and so that you’re not rubbing up against people who might have lesions that you can’t see.”

Symptoms to look out for are fever, malaise and lymph node swelling, with a rash developing about 24 to 48 hours later. Individuals should seek medical care before being around other people or having close contact, she said.