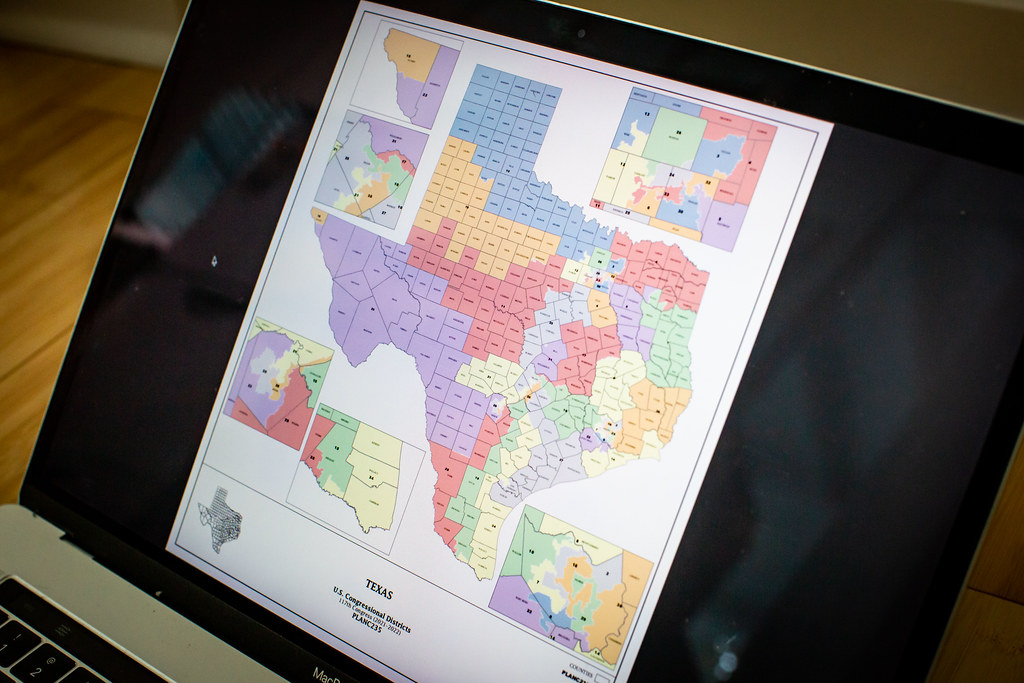

New districts are being created to account for population growth in Texas. The Legislature held hearings on the proposed maps last week heard from constituents again on Monday. Texas will have two new Congressional districts. As it stands now, neither of them will contain a majority of Latino residents or people of color.

This redistricting process is crucial because politicians are supposed to reflect changes noted in the census. The 2020 census showed that 95% of Texas’ population growth comes from communities of color.

Miguel Rivera is voting rights outreach coordinator with the Texas Civil Rights Project. Rivera told Texas Standard that partisan gerrymandering in Texas is often linked to racial gerrymandering and that there are still some protections for communities of color provided by the Voting Rights Act.

Listen to the interview above or read the transcript below to learn more about the maps for the state’s two new congressional districts.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity.

Texas Standard: How do these maps incorporate growth, as you read through them?

Miguel Rivera: Quite frankly, they do not reflect the growth in the state. Maybe numerically in the two new congressional districts Texas was apportioned, but not in how they’ve been drawn.

Could you say a little bit more about what stood out to you in terms of how they were drawn?

The census recorded about 4 million new residents over the past decade, 95% of which were people of color. The two new districts that Texas received at the congressional level, Texas 37 and Texas 38 [as] proposed would be majority white. So they do not reflect the communities that have driven the growth over the past decade.

As you look at the geography of these maps, what do you see and how do you see these communities being broken up? Or are they more being packed together?

So it’s a twofold answer, and you’ve alluded to both the packing and the cracking. We know that Texas in particular has a long history of racially gerrymandering in every round of its redistricting. And so we’re seeing districts that, for the most part, keep urban areas whole but have on the suburbs cut up some of these very diverse communities and angered them with rural constituencies that, quite frankly, don’t share the same interests or concerns at the electoral level.

When you look at, say, Congressional District 6, does that stand out to you? And how so?

Congressional District 6, and there are several others across the state – you can tell that they’ve also taken into consideration partisan trends over the past few years and election cycles. But they have also been drawn that would basically cement partisan status and almost all of these districts for the next decade.

Well, in the aftermath of the November elections, I think a lot of Latino political scholars and political scientists noted that you can’t think of the Latino vote as monolithic – as singularly Democratic or Republican. So as you look at these maps, how do you come to the conclusion that Latino communities and communities of color are not represented in these maps?

There’s a specific measures on how you can gauge whether a district serves a specific community or not. And part of that is [determined] by looking in the voting age population of specific districts. And so when we are looking at making sure that communities of color can’t elect candidates of their choice. partisanship is not included in that analysis, just the community’s ability to actually rally behind a specific candidate, following their status as a protected group under the Voting Rights Act.

Someone listening to you might say, Well, yes, that’s what happens with parties in power. The redistricting process has been upheld numerous times by the U.S. Supreme Court, and the court has said this is a political issue fundamentally.

That’s why I think it’s really important to highlight some of the protections that we already do have against certain types of gerrymandering. Racial gerrymandering is outlawed under the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act. But we also know just through pure data that racially polarized voting is also a thing. So very often it’s very hard to separate racial gerrymandering from partisan gerrymandering.