From KERA’s Art&Seek:

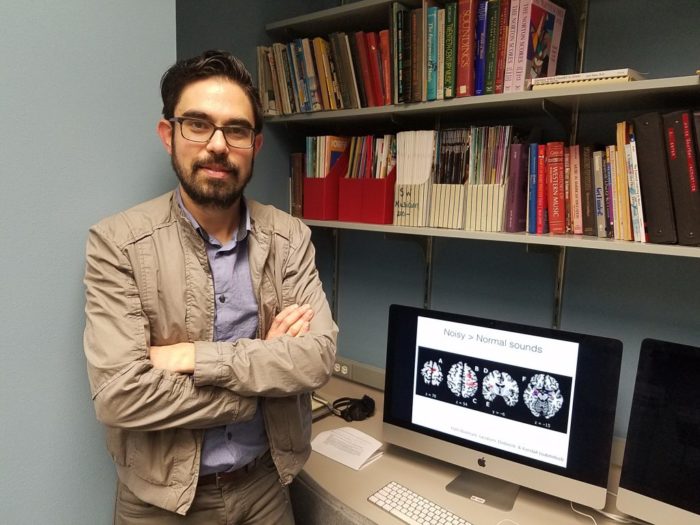

For years, Zachary Wallmark has found himself caught in between two worlds – with one foot in science and the other in music. He now teaches musicology at Southern Methodist University, studying how musical sounds affect the brain. Wallmark just won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to continue his research.

Like so many aspiring musicians, Zachary Wallmark did the “New York City” thing in college. As a bassist, he played corporate jazz gigs uptown for the money and avant garde free jazz, something quite a bit more eccentric, downtown for the love of it.

“One of the things I noticed at these gigs was the people who liked what we were playing were very emotionally invested and just swooned at these sounds,” Wallmark said. “But a lot of people I played these to – friends, roommates – just thought it sounded like a bunch of awful noise.”

Those nights performing got him thinking about why people had such strong and polar reactions to the same music – and that led him to neuroscience, specifically the nature of human emotional and social responses to musical sounds.

Wallmark has a master’s degree and a Ph.D. in musicology – not science. But at SMU, he’s helped launch a new lab, blending the two. He and his students study what our tastes and motor reactions to sounds might say about human empathy.

“Because I’ve lived this,” Wallmark said. “I’ve seen these sorts of reactions. I know how empathy works in musical contexts. I know how empathy can utterly break down. I know how you can lose your audience just as easily as you can have them eating out of your hand. Actually it’s far easier to lose them. What’s going on with people when they experience these intense emotional and social reactions to music?”

So he began to answer that question first by playing sets of sounds for his subjects and taking scans of their brain. Pleasant sounds – a round, smooth note on the clarinet. And not so pleasant sounds – a gritty, raspy honk.

“What we ended up finding was that there’s really not that much of a difference in the brain when you’re listening to sounds you really like,” he said. “However, when you’re listening to sounds you dislike, a whole bunch of regions light up – including motor regions, areas that control movement, and the limbic areas, the so-called emotional circuitry.”