In the heyday of silent movie comedy, Buster Keaton was one of its biggest stars and most innovative practitioners of the form. His life, which began just before the dawn of the 20th century and ended in the 1960s, intersected with some of the most consequential developments in entertainment, law, journalism and politics of the era.

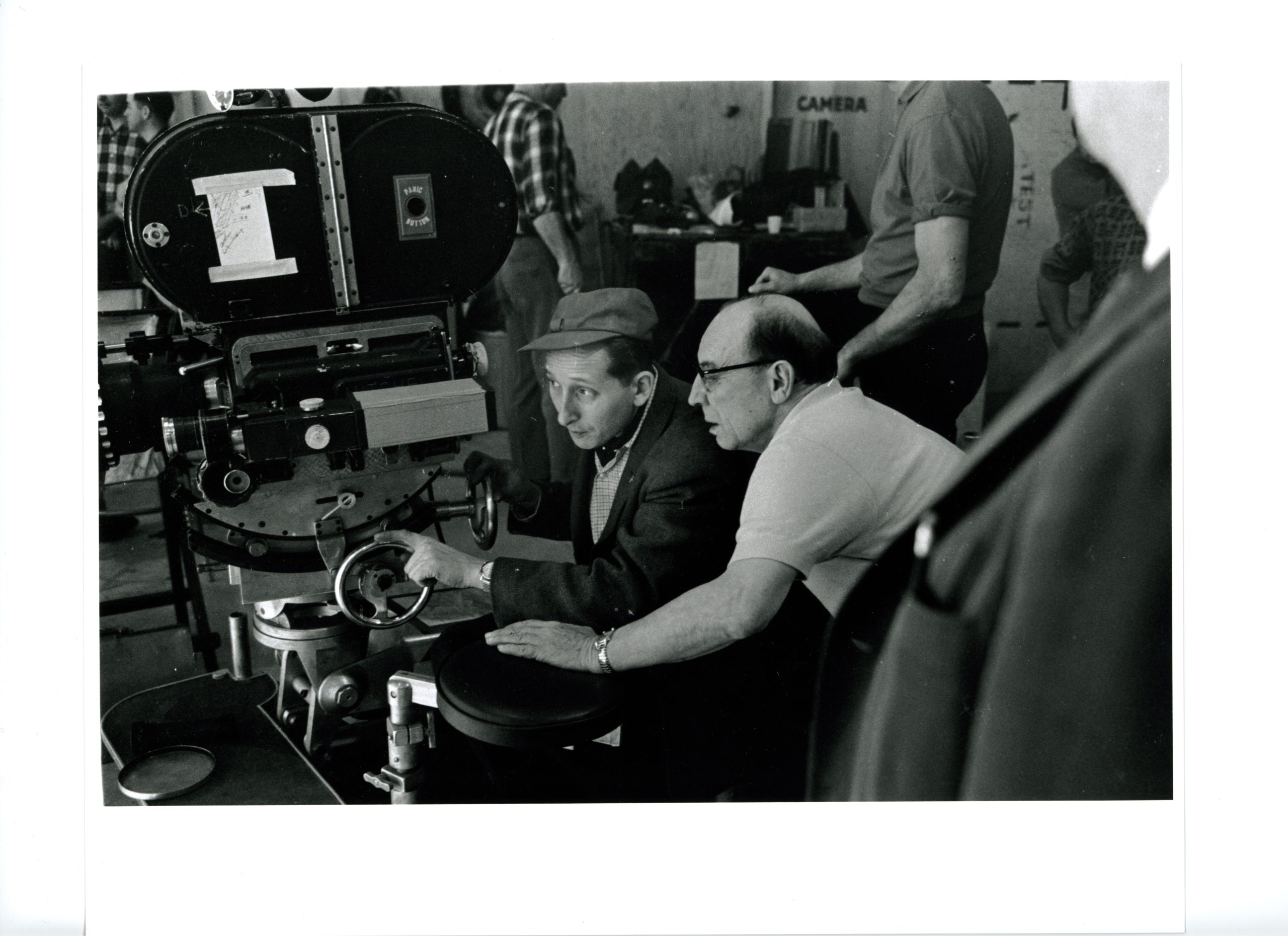

Dana Stevens’ new biography about Keaton is “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, The Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century.” Stevens is film critic for Slate Magazine and cohost of the weekly “Culture Gabfest” podcast. Stevens says that while “Camera Man” tells the story of Buster Keaton’s life, it also aims to put the comedian in a larger context, and to refresh his legacy for modern audiences.

“Whether you know it or not, his influence is all over movies you see all the time: from action movies to any kind of stunts or slapstick comedy,” Stevens said. “He had an enormous influence in terms of being right there, present at the birth of so many of those genres.”

Keaton was born in 1895, the year motion pictures were first projected for an audience by the Lumière brothers. Along with other performers and filmmakers who grew up with the movies, including Charlie Chaplin and Mabel Normand, he invented the elements of storytelling and comedy that would influence generations to follow.

“I feel like he grew up alongside cinema,” Stevens said. “It helped to make him. He helped to make it. And that’s the process I’m trying to chronicle in the book.”

Alongside the milestones of Keaton’s life and work, Stevens writes about people and events that intersected what Keaton was doing. An early chapter chronicles changes in child welfare laws at the turn of the 20th century, and how a focus on child labor and neglect impacted Keaton – then a child star on the vaudeville circuit. Another chapter focuses on the many women who directed and produced movies in the 1910s, only to be sidelined as the movie business grew.

“It was amazing to me how often, if you would just take some event, or moment, or even a year from his life and start researching out from that year, and what else happened, how many connections you could make,” Stevens said.

Keaton’s career floundered after the silent era, not because – as happened to so many other stars – he couldn’t work in sound films. Rather, Keaton was no longer in charge of his own productions, Stevens says, and MGM, where he worked as a contract actor in the early 1930s, would not allow him the creative control that Keaton needed to succeed. He became depressed and abused alcohol and spent several years unable to work.

“Too often, I think, his story is told as if it’s just a pure tragedy,” Stevens said. “But, in fact, that was a relatively small part of his life.”

She says she has affection for Keaton’s successful efforts to turn his life around.

“He managed to claw his way, and struggle his way back, and by the 1950s, he was getting regular work in television. So yeah, I think his ending is a happy ending.”

During the early television era, Keaton hosted local shows and worked constantly as an actor in film and TV projects. In “Camera Man,” Stevens pairs Keaton’s reemergence in those years with the postwar consumer economy of the 1940s and ’50s.

Stevens says much of Keaton’s surviving silent film output is available to view for free, since it has entered the public domain. She recommends the 1920 shorts, “One Week” and “Cops” to anyone looking for example of Keaton’s talent.