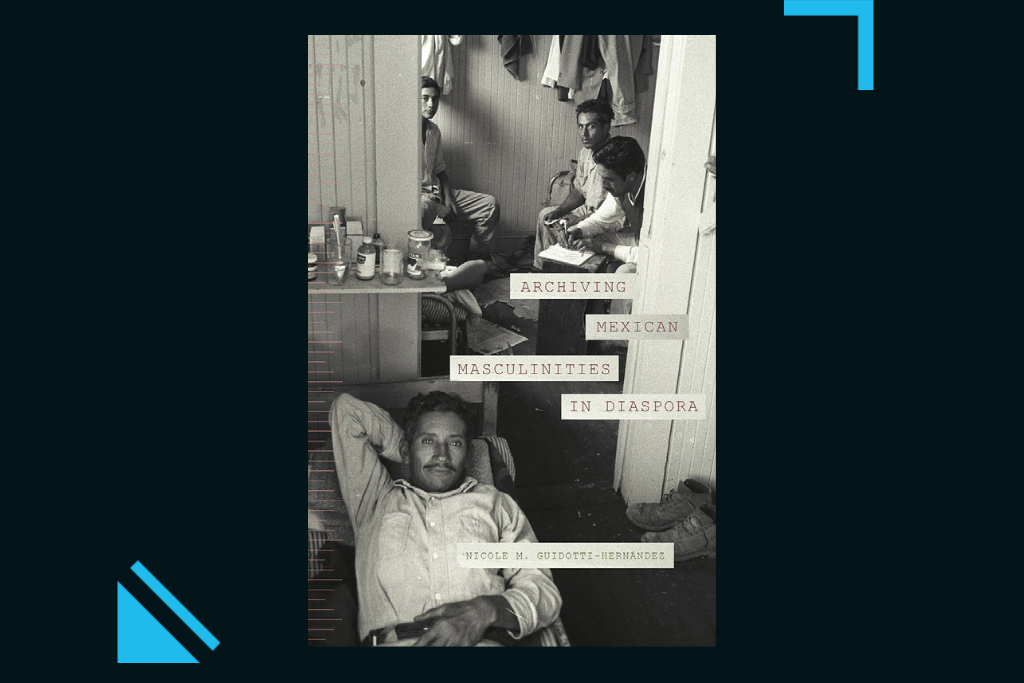

“Archiving Mexican Masculinities in Diaspora” is the latest book from Nicole M. Guidotti-Hernández.

Guidotti-Hernández teaches English at Emory University, and specializes in American Studies and Mexican-American and Latino Studies. She told Texas Standard that for decades there’s been only one narrative about immigration, braceros and anarchists fleeing the Mexican Revolution. But her research provides an alternative narrative.

Through never before published photographs and letters, Guidotti-Hernández pieced together this alternate narrative.

This interview has been edited lightly for clarity.

Texas Standard: Your book can be divided into two powerful narratives: one about braceros – the mostly male guest workers from Mexico who came to the United States during a program that started during World War II; the other about an anarchist and a journalist from a prominent political family in Mexico. What are the common threads between these two stories?

Nicole Guidotti-Hernández: The main thing that links them together is the desire for freedom, the desire for economical mobility. One of the things that was an outcrop of the book that I didn’t actually intend to do was writing a history of labor in the United States, roughly from 1900 to 1956, because that is the main link between anarchists and braceros, as they’re both advocating for and part of a laboring system that is unfair, that is uncompensated where they become part of an underclass.

Also, just how do you write a history of a family that then reflects the national body politic, right? How does one family’s story reflect the history of Mexico? How does one family story and all of these stories of these gentlemen that I write about reflect the history of the U.S. and its dependence on Mexican labor and Mexican migration, and now Latino migration here in the 21st century?

Braceros have often been treated merely as workers, as commodities, and not as people with complicated sexual narratives. What did you want to convey about Mexican masculinity through this book?

There are a couple of things that I wanted to indicate with the title. One is that there are some of the records that we don’t know about people’s daily lives, the way they’re interacted, the way they develop familial relationships, camaraderie, homoeroticism, pride that is erotic, and attraction between people of the same sex, as well as intensive political attachments and commitments to each other.

And that was one of the things that I really thought was important about writing this book is that in Latinx, and Mexican studies more broadly, we often only talk about masculinity in terms of machismo, a kind of embedded misogyny that men of Mexican descent practice on a daily basis. And while my research shows that yes, there’s very much of that, there are also times when that narrative of masculinity falls apart. And so we look at the correspondence of Marcus or the photographs of braceros, and we see men interacting in intimate spaces are in physical proximity to each other. They’re also expressing sentiments of love and longing and loss and regret in their letters while they’re in the United States.

The book features some really powerful, previously unpublished photographs. How did you find these very intimate images?

So there’s two places: one is in private collections, and then two, is the public collections. And so, in particular, this main archive of photographs about the braceros. The Leonard Nadel Collection is held at the Smithsonian Institution Museum for American History. There are over 20 photographs, and I started to think about, why is it that we only want to show images of braceros as laboring bodies? And what does it mean for us to think about them as subjects and individuals who have desires, wants and needs, who see themselves as political actors and want to be remembered that way?

So many of these photos are really compelling, but the one with the man showering – you can just see the muscles that, no doubt, came from hard labor.

I want to put this in context: you really see just the aesthetic sensation of the worker’s body in the same way that Michelangelo’s David statue celebrates the masculine figure. I think this photograph does some of that labor as well. The other thing it shows us, though, is that that proximity between the photographic subject and the photographer is quite close, and it creates a sense of intimacy where we’re looking into his private life and into his face. And one of the questions that I raise is, does he know he’s being photographed? And if so, does he consent to being photographed in the nude?

And I think there’s a lot of complicated dynamics going on in there. So, on the one hand, we have this beautiful aesthetic sensation of this body that is not constructed through weightlifting or leisure, but through hard manual labor. And on the other hand, we have this snapshot. It’s the intimate daily lives of these men, both in relationship to each other, but also in relationship to the photographer who’s taking these pictures.