There is one thing many Republicans and Democrats – especially here in Texas – have agreed on for some time now: that the U.S. immigration system is broken. What can’t be agreed upon is how to fix it. But what becomes of the people directly impacted by this system? Efrén Olivares wants to help tell some of those stories, along with his own.

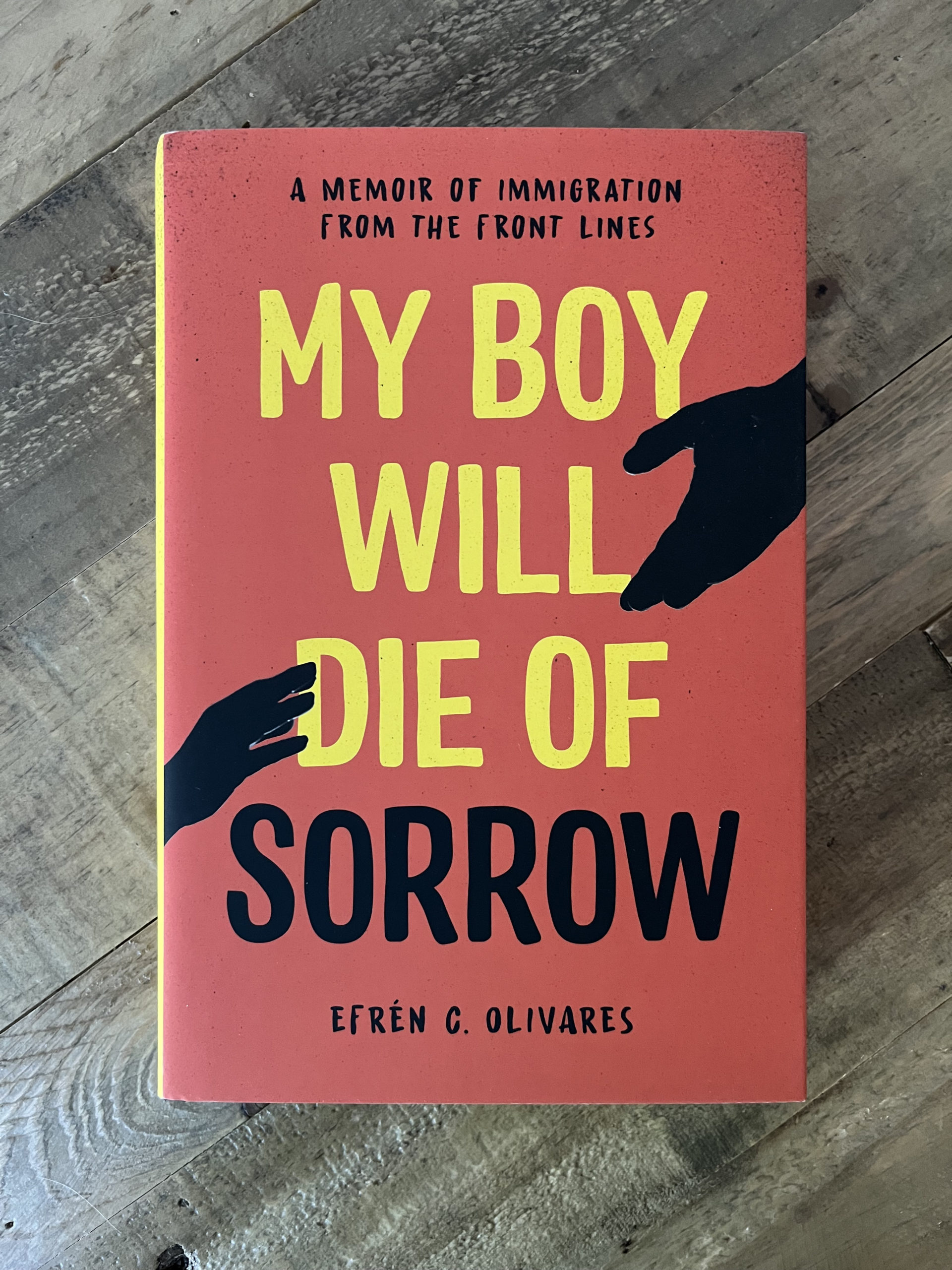

Olivares, deputy legal director of the Immigrant Justice Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center, joined Texas Standard to discuss his new book, “My Boy Will Die Of Sorrow: A Memoir of Immigration from the Front Lines.”

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: As an immigration lawyer, you represented many of the families who were affected by the zero-tolerance policy during the Trump administration. But you have an even closer connection to your clients in that you were an immigrant yourself. Could you tell us a little bit more about your story, how you came to the U.S.?

Efrén Olivares: Certainly. You know, at the time I represented the separated families, I never thought of my own experience as comparable to theirs. But in fact, some 25 years earlier, I had moved to the U.S. In fact, my father had moved first while my mother and my siblings stayed behind. We couldn’t come because we didn’t have the legal paperwork to join my father. And he did, so he came to the U.S. in search for work, you know, “economic immigrant looking for work.” And he found work as a school bus driver.

So for about four years, he was in the U.S. and we were in Mexico. He would visit us occasionally, you know, once a month or as often as he could for a weekend. But he was certainly not in our day-to-day lives between the ages of 9 and 13, for me, until we were able to join him. And I did not know at the time how meaningful that difficult experience would be for me, as later on, I would go on to become a lawyer and an advocate for immigrants.

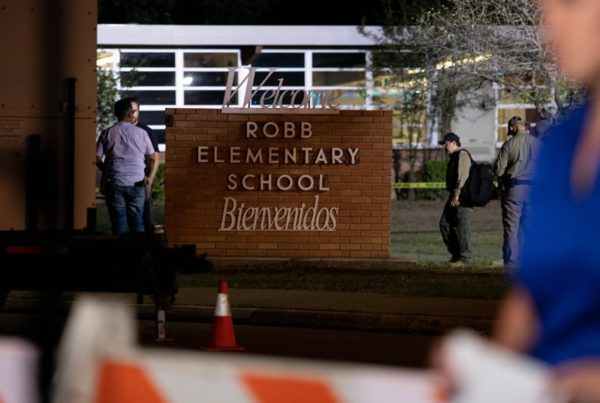

As you spoke with your clients, as a matter of representation, what were some of the stories you would hear, especially during that zero-tolerance policy period where families were being separated?

You know, it was heartbreaking stories of parents coming into court believing that their children would be waiting for them at the Border Patrol station later that afternoon because they had been led to believe so by some of the agents who separated them. And I had to be the one to break it to many of them that in fact, their children were likely not going to be there. Their children were likely at a shelter, and we had no idea when they might see them again. And in fact, some of them never saw their children again.

It was heartbreaking because for many of these families, they had fled violent or life-threatening conditions in their home countries. And just when they thought that they had made it to the safe place, to the haven, where they would be protected and welcomed, they were met with even greater abuse and family separation.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but you know, you think about how the immigrant story is often told in the United States with the glorification of Ellis Island and so on and so forth. And, well, you get a sense that that the border has come to replace, if not reorient, the way that we think about migrants – and if it hasn’t completely, perhaps it should. Do you think that’s fair? I mean, as a kind of takeaway to think about how you’re trying to reframe this debate over immigration?

I think that is fair. I think writing this book led me to realize the extent to which the anti-immigrant arguments that we hear today have been around for at least 150 years in this country. The ideas that, you know, they are coming to take our jobs, that they are driving up crime rates, that they are even bringing in disease. All of these arguments are nothing new. They have been around since the times of Ellis Island, even before then with the Chinese Exclusion Act in the late 1800s. And I think it’s important for us to come to terms with it and not sanitize or romanticize the history of how immigrants have been treated in this country, particularly those who are not perceived to be white.

So at Ellis Island, even though it’s like you said, glorified, sometimes children were put in cages, much like children were put in cages in the last few years at the southern border. And it’s important to come to terms with that, because then that takes away the validity of these arguments against immigration, that the data does not bear out. You know, crime rates are lower in many immigrant communities than in the native-born population, etc. So that reframing is important.

And it’s also an important highlight that what we saw in 2018 was not really an anomaly. It was a crisis for sure. But it wasn’t the first time that immigrant children and migrant families knocking at our doorstep asking for help and protection were treated this way. It happened again in the late 1800s, early 20th century, during the Japanese internment camp, during World War II – so we’ve seen it before. This was the latest iteration.

And this time around there were cellphones around for people to document the abuses. You might remember in mid-June of 2018, an audio was leaked of children crying in the detention facility. And that was a turning point that summer because hearing those children – hearing their voices – really turned public opinion against this policy, even from the anti-immigrant corners of the public. The reason I think that audio was so powerful was that it was not video, you could not see the color of the skin of those children. You could only hear their cries, and all children cry the same. They all say “mama” or “papa” the same. And that was so powerful.

But why were the cries of their parents not received the same way? And that’s one point that I want us, all the readers and the public in general, to think through. Why is our position different? When you hear the father or the mother crying about the abuse that they’ve endured. But only when you hear the audio of their children and not see the color of their skin, that’s when the public opinion really, you know, it felt like a line had been crossed and we couldn’t go there.

And obviously, this comes from your own experience, how kids are affected by all of this. But as people hear you talking and they think about the stalemate over policies, how would you like to see those policies change? And is it possible to get a bipartisan consensus on reform that could work?

I think it’s absolutely possible. It comes down to a matter of political will. There’s absolutely no doubt in my mind that this country can process immigrants and asylum seekers coming in through the border. So I think the process for reform ought to be, you know, include something for asylum seekers, right? So those people fleeing violence, that threat of persecution, can have an orderly and quick way to come to the U.S.

And then when it comes on the economic side, I mean, there’s a shortage of workers in the U.S. right now. There’s a labor shortage, and yet we’re turning people away at the border. So both for the humane reasons as well as for economic reasons, there ought to be enough of a political will. Now, the gamesmanship and the calculus in Washington, D.C., in Congress, especially during an election year – I’m not that naive to think that that is not going to get in the way. It will. But if it comes down to what the immigration solutions ought to be as a matter of public policy, there certainly ought to be the way that benefits the American public, the immigrants and in fact the political parties as well.