Because 1968 was such a historic year, 2018 is packed with momentous 50th anniversaries. It was a year of ideological divides, assassinations, Vietnam – and a Texan in the White House tasked with leading the country through it all.

By 1968, during the twilight of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration, there was one more piece of Great Society landmark legislation to see through. On April 11, 1968, LBJ signed something called the Fair Housing Act. It was designed to protect people from discrimination when renting, buying, or trying to get money to buy a house. As we mark the 50th anniversary of the law, historians say it’s had very mixed success.

Dr. Peniel Joseph is a professor at the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the History Department in the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, as well the founding director of the LBJ School’s Center for the Study of Race and Democracy.

Joseph says it’s no accident that the law was signed at this time.

“The Fair Housing Act was passed the week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. so in a way it’s the president and Congress’ effort to use legislation and public policy to try to stem the tide of anger, that’s really passed before the summer,” Joseph says. “And this is the era of long, hot summers that had really begun in 1963 with Birmingham, Alabama.”

Over the decades, implementation of the policy has been anything but consistent.

“It’s an important federal law, but what we see is by the early 1970s, federal construction on open housing, or public housing, ceases,” he says. “And we see successive administrations intermittently try to enforce the Fair Housing Act.”

In fact, Joseph says, enforcing the law tends to depend on who’s in the White House – whether the federal government is being led by Democrats or Republicans – and who they’ve chosen to run HUD and the Department of Justice. Rather than ending housing discrimination, the Fair Housing Act changed it.

“We still have discrimination when it comes to African Americans, Latinos who have vouchers, who have Section 8, or who just really want to move into predominantly white areas, and the discrimination they face is simply people telling them that there’s no room, there’s no housing,” Joseph says. “So it’s not going to be an overt kind of discrimination. People aren’t name-calling, you just simply don’t get an opportunity to move into that neighborhood.”

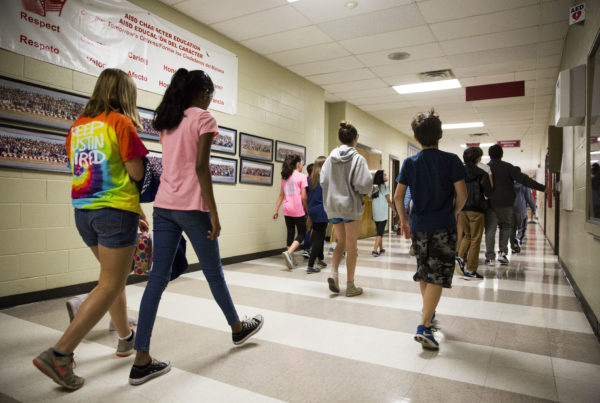

Joseph says the Fair Housing Act was intended to create equal opportunities for low-income families.

“So even though you don’t own a home, you can send your kids to local neighborhood schools, you have access to the supermarkets that we have here, you just have access to the safety of the community. And that’s where fair housing was supposed to be a game-changer,” he says. “And in many ways, unfortunately, it hasn’t been.”

In different states and cities, the local response to the Fair Housing Act has varied. Joseph says that, in the South, residential integration has been very slow.

“What we saw was white flight that was really brokered by both private and public entities. Private real estate interests, banks – and public, with the way in which zoning laws and other federal, state, and local municipalities divided up school districts,” he says. “So it’s been really, really difficult in the South to promote residential integration.”

Ultimately, Joseph says the legacy of the Fair Housing Act isn’t simple.

“It’s a mixed bag because 50 years later, we don’t necessarily have the political and legal institutions that want to ensure that for all Americans,” he says. “But it’s important because of the precedent that it set. So maybe in subsequent generations we’re going to have people really look at that act and say, ‘We’re going to try to make this as meaningful for all American citizens as possible.’ And if we do that, that’s going to be a game-changer.”

Written by Jen Rice.