A new book looks at the current state of gender inequality and makes some dire observations, though perhaps not the kind typically touched upon.

“Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About it” points out that, while recent decades have seen women make progress in several areas, men have lost ground in fields like education and mental health.

For author Richard Reeves, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institution, the goal of gender equity means looking compassionately at the problems boys and men are facing while remaining passionate about women’s rights and the work that still needs to be done. He spoke to the Texas Standard about his work and some of the structural solutions he proposes to address the troubling state of men and boys. Listen to the story above or read the transcript below.

This transcript has been edited lightly for clarity:

Texas Standard: Tell us a little bit about the inspiration for the book. There’s been so much conversation around the ideas of tearing down patriarchy and patriarchal systems that I would think that some people might be a little surprised that you’re taking on this role as an advocate for men and boys.

Richard Reeves: I’ll be honest, I’m somewhat surprised myself. It’s not necessarily a book I would have expected to write, but I think in some ways it’s important to see that, as the result of some of the successes we’ve seen by the women’s movement, it’s certainly not “job done, mission accomplished” by any means. And you mentioned some of the statistics, but there has been extraordinary progress in recent decades. And I think one of the results of that is, is to allow us to look at some gender inequalities that go the other way.

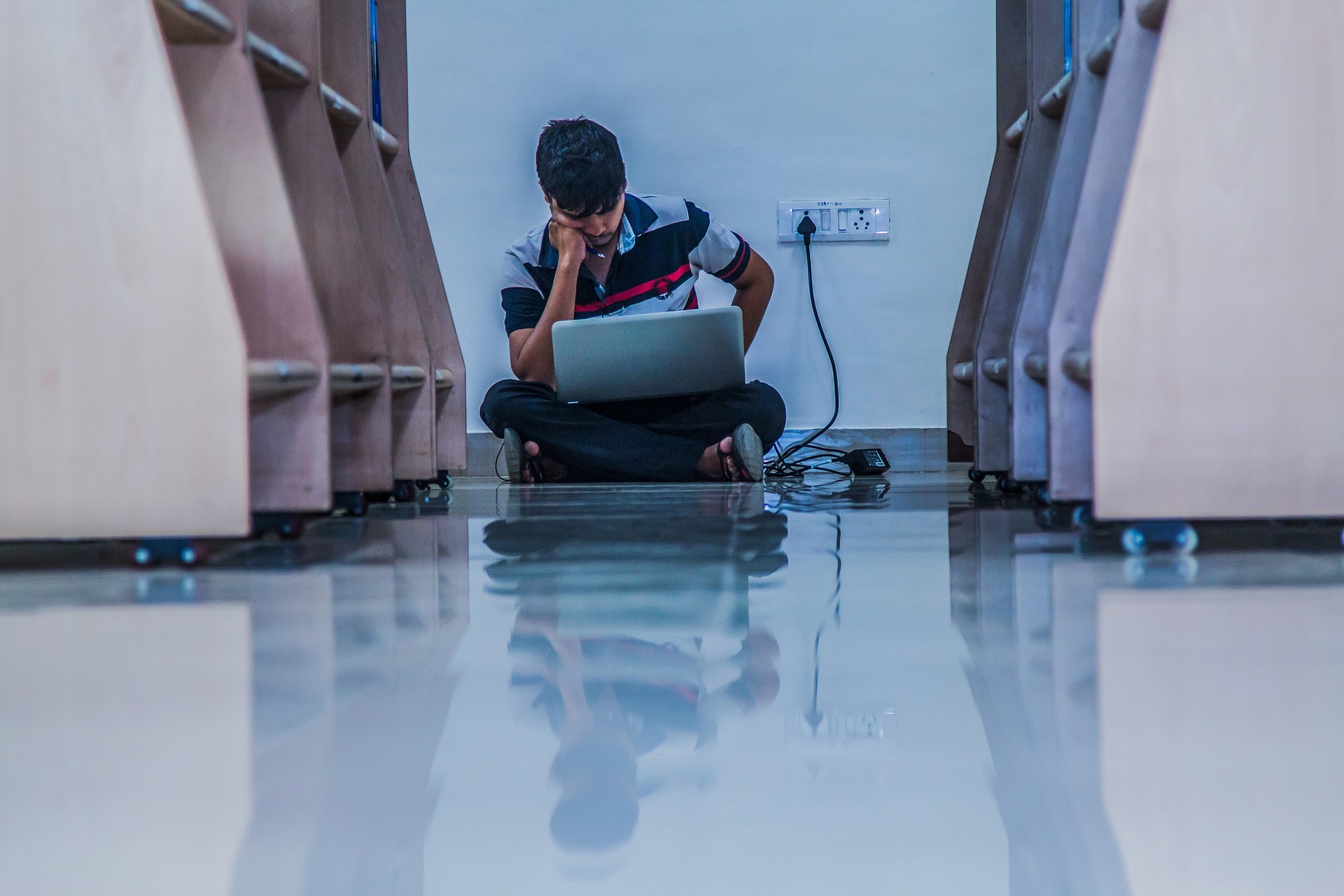

For example, the way that boys and men are falling so far behind in education and have been doing over the last few decades and to be really troubled by that. And so I do think it took an enormous effort over recent decades to get us to a point where we could even have this conversation. But the facts are what they are. And when you see that, say, the gender gap in getting a college degree is actually wider today than it was 50 years ago, but the other way around. So in 1972, it was men were 13 percentage points more likely to get a four-year degree than women. Now, women are 15 percentage points more likely than men. So there are many areas where the script has flipped, and so I think it’s important we look at both.

Well, some would say that given history and, not to mince words, perhaps it’s about time that the shoe were on the other foot.

Yeah. I mean, that’s an instinct that I’m sympathetic to, partly because it’s just been so quick. But if we pause for a moment, I actually don’t think there are that many people who think that the next thing to do is have 10,000 years in which men fall behind women, and then we’ll call it quits. The boys and men we should be most concerned about are those who are from the least advantaged backgrounds: working class men, men of color. Most men today earn less than most men did in 1979, but men at the top are doing quite well. And so it’s important to look at this through the lens of class and race and not just through the binary of gender.

Throughout the book, you talk about being the father of three sons – George, Bryce and Cameron – and you dedicate the book to them. I’m curious how much of your thinking around this subject has centered, or been perhaps launched, by your thinking about your own kids?

I think it’s clearly been influenced by that. I mean, I say that I’ve spent 26 years now and counting worrying about boys and young men, but really just my own three. Now I’m worried about many more. And it’s clear that the conversations we’ve had about what it’s like to grow up as a young man today, I do think it’s very different than it was even even for me, particularly as they look around the education system and they’re negotiating new relationships based on an assumption of equality, including economic equality, and how that’s been for them and how they are trying to adapt to this new world.

And to be clear, they’re from very privileged backgrounds by any reasonable definition of the term. And so they’re not really representative of the boys who are most struggling, but they’ve had their share of struggles. And one of the things I’ve noticed is that parents are much more likely to tell you about how worried they are about their sons than they are their daughters, especially in an education. And so all scholarship is a little bit autobiographical. It’s just a question of whether we admit it or not. And so I’ve definitely been influenced by watching my sons grew up in the U.K. and the U.S., actually.

One of the ideas that you have here is holding boys back a year before they start school. You use the sports term “redshirting.” What’s the thinking?

Yeah. Or another way to frame it is to accelerate girls forward a year. But essentially the idea is to stagger the age at which boys and girls enter school. We talk about some of the gender gaps, but we see them in high school. The top 10% of GPA scorers, two thirds of them are girls. The bottom 10%, two thirds of them are boys. And so girls are doing much better in high school. One of the reasons for that is because girls’ brains develop more quickly than boys. There’s not really much argument about that in neuroscience.

There’s arguments about whether men’s and women’s brains are different in the end. The answer is not really. But boy, there’s a big difference between a 15-year-old girl and a 15-year-old boy on average. And it’s mostly because of the development of certain skills: of prefrontal cortex, organization. It’s the bit of your brain that makes you turn in your chemistry homework and girls develop those skills earlier. That’s just a fact of neuroscience. And so what we do by, if we hold boys back a year or accelerate girls a year, what that means is that they develop mentally a bit closer in age.

One of the issues that frequently comes up in this discussion is what’s meant by equality and inequity. We’re talking about equal opportunity. We’re talking about equality of outcomes as measured across, say, some kind of index of performance. How do you see this issue as it relates to gender?

Yeah, well, I mean, the distinction is an important one and it’s been quite, quite powerful because what equality would suggest is “treat everybody the same.” But equity takes into account differences between individuals and certain groups. So what does that mean in terms of gender? Well, it means, for example, that there are going to be some areas where you really are going to want some ways to help women, specifically – perhaps around pregnancy discrimination laws.

But there are going to be other areas where the biological differences might mean, for example, in education, that you might want to stop boys in school a year later, as we just discussed, or you might need more recess and Phys Ed for boys on average, and so on. So I think there are ways in which you can just take into account some of these differences that occur without betraying the ideal of equality. So equity is a way to operationalize equality.

Some people would say, “Is now really the time for us to be focusing on men and boys?” After years of being treated as second-class citizens, a lot of women are just now having an opportunity to bring about the sort of change that they’ve always wanted to bring about, but they have not had the tools or the opportunities to do so. How urgent is this?

I think it depends where you’re looking. So again, I think the key thing here is to really resist this idea that it’s a zero sum. There is nothing here that in any way goes against continued work on behalf of women and girls. I think it’s perfectly possible to keep doing that. But, are there areas where we should worry now more about boys and or men than women? Sure. Education. We’ve talked quite a lot about huge gender gaps now and growing.

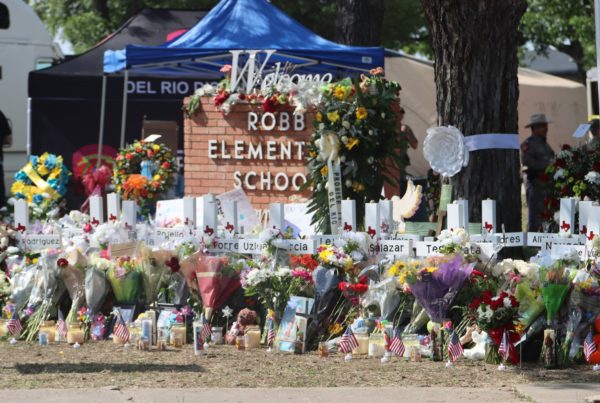

But there are other areas, too. Men are three times more likely to die from a death of despair: from suicide, drugs or alcohol. Significantly more. I mean, the suicide gap just grew last year. So it’s a huge risk. For young men, in particular, suicide is typically one of the highest or second-highest causes of death. And so I think it is possible to be passionate about women’s rights and what continues to need to be done on that front, but also compassionate towards many of the problems that boys and men are facing, especially those from the least advantaged circumstances.