From Texas Public Radio:

Infertility can be heartbreaking for many couples struggling to have their own biological children. Some scientists at the University of Texas at San Antonio are trying to understand the mystery of male infertility. And they’re conducting their research one cell at a time.

In a lab at UTSA, a rectangular box about the size of a toaster is yielding incredible data. It’s a single cell RNA sequencer, one of many machines Brian Hermann, Ph.D., is using to study the genesis of male infertility.

“Single cell RNA seq allows us to examine all the genes that are expressed in any given cell,” Hermann says. “So we can look at anywhere from hundreds to thousands and tens of thousands of individual cells.”

The cells he’s looking at are from the testicles of mice serving as a model for a human problem: a lack of sperm. Sperm producing cells come from stem cells, but somewhere along the line for an increasing number of men, there’s a problem in the formation of those cells, some developmental process that perhaps is going awry.

These instruments enable Hermann to pinpoint specific sets of genes. “Up to a total of 9,216 of those sets at a time,” he says. “We can be precise in terms of measuring all the genes that are expressed in an individual cell.”

Herman says this wouldn’t have been possible five years ago. It’s like looking at grains of sand, not the beach.

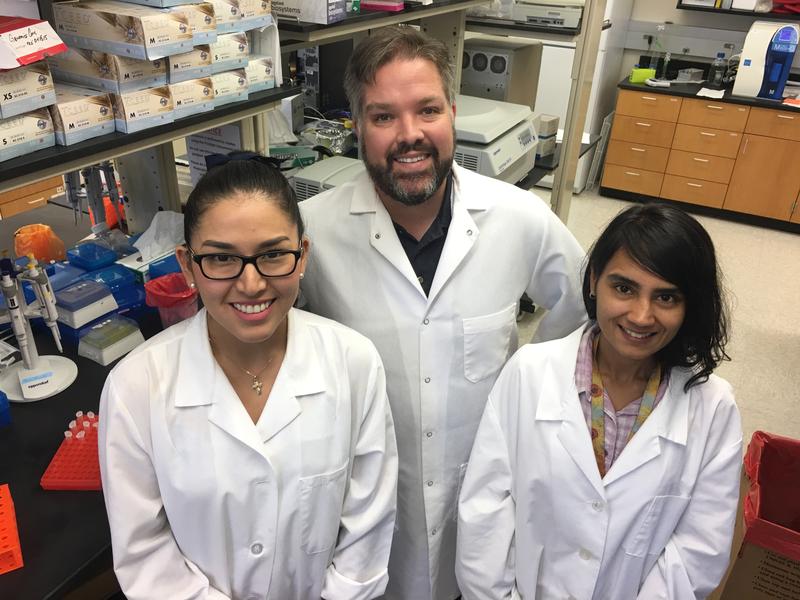

Graduate research assistant Lorena Roa is part of the male infertility project. She’s curious about what tells stem cells to become sperm-producing cells or something else entirely. ”

I want to figure out what is that mechanism or what is it that tells those cells to go one path or another,” Roa says.

Fellow doctoral student Anukriti Singh shares that interest. “I’ve always had a curiosity about stem cells and how they make their decisions,” she says.

The idea is that if scientists can identify why some sperm-making cells don’t form normally, there may be a way to intervene, opening the door to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment.

Infertility affects about one in six American couples. Hermann says that drives his innate curiosity in the lab.

“I know that there are people out there who are desperate to have their own children,” he says. “For folks that are infertile, it’s the most devastating disease.”

The National Institutes of Health has awarded Dr. Hermann a $1.5 million dollar grant for the next five years to study the problem with cutting-edge technology.