In Friendswood ISD, southeast of Houston, Heather Darcey’s son Logan started acting out in first grade.

“It was just constant emails from the teacher and constant negative behaviors — being sent to the office, he was crawling around on the floor, hiding under things,” she recalled. “I didn’t really know what to think of that.”

He was eventually diagnosed with dyslexia, ADHD and autism.

The years rolled by — second and third grade at one school, fourth and fifth at another — and the behavior issues continued.

“I knew that he was still having these episodes where they would have to clear the room,” she said. “He was destroying the classroom, throwing things. At one point, his teacher was restraining him and he head-butted the back of her head, and she got a concussion. He got suspended from school for that.”

That’s the type of situation when state law allows for restraints — when students pose imminent risk of serious harm to people, or destruction of property.

But Darcey didn’t know how often Logan was restrained.

He wound up alone in a classroom with no other students every day. Darcey said he had no friends. He would text and call her.

“‘Help, help, help me,'” she said. “You know, ‘Mom, help, help. Where are you? Where are you?'”

She thinks the isolation made his behavior worse. And the restraints continued. She asked about it, and the school began notifying her for the first time during fourth grade.

Parental notification is legally required, explained attorney Meredith Shytles Parekh. She represents foster kids in special education for Disability Rights Texas.

“Districts are required to send notice within 24 hours of the incident so that they have written documentation,” she said. “I think we see that that notice doesn’t go out often or doesn’t go out in a timely manner.”

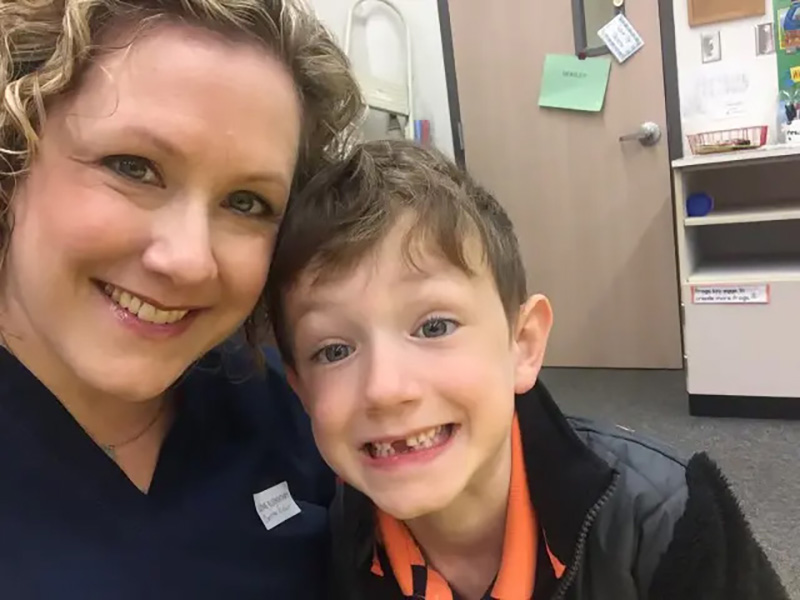

Heather Darcey’s son, Logan. Darcey said her son has been restrained multiple times since the first grade.

Photo courtesy of Heather Darcey

In October, a Hearst Newspapers investigation found that over half of the state’s more than 1,200 school districts didn’t report a single restraint to TEA in the school years from 2018 to 2021.

Parents with kids in special education report routine use of restraints and physical discipline outside of emergency situations, often without required notification.

“If you talk to Logan, he’s been being restrained since probably first grade,” Darcey said. “When I brought it up I said, ‘I’ve never gotten anything written,’ and then they started sending home stuff saying that he was restrained. But Logan will tell you about being dragged through the hallways, being put in a room — just all kinds of stuff — and being restrained multiple, multiple times.”

Friendswood ISD said the district “follows guidelines set forth by the TEA relating to discipline and restraints.”

Now, Logan stays home while his mom fights the district for private, off-campus placement where he can get specialized services.

Those off-campus programs have to be approved by the Texas Education Agency (TEA), and school districts that can’t provide adequate services will pay for students to attend. But it’s often difficult for parents to convince districts to fund those placements — and sometimes, even at these specialized schools, students are still improperly restrained and physically disciplined without parents knowing.

Amanda Weaver is in Fort Bend ISD, southwest of Houston. In 2019, her son — whose name is also Logan — attended Dulles High School. One day, she got a call from a district staffer.

“He was like, ‘Okay, I just want to let you know that he had fallen down on the way to the bus,'” she recalled. “Then, about 15 minutes later, I have two other children that also were in school at Dulles come home in a panic because there’s this Twitter video, and it’s Logan.”

Logan was standing in front of a vending machine. A school staffer grabbed and yanked him by his backpack.

He stumbled to the ground, and she kept pulling while yelling “Get up! Get up!”

“I see this video, and I’m through the — I’m angry and I’m upset,” Weaver said. “And all the emotions come flooding in because of the drastic difference in what I was told versus what really happened.”

Fort Bend ISD said the staffer is no longer with the district, and wouldn’t comment further.

Weaver was able to get Fort Bend ISD to pay for her son to attend Avondale House, a private program in Houston that had been approved by the Texas Education Agency.

In January, TEA denied Avondale’s approval, saying that the school used inappropriate restraints and corporal punishment, among other violations. About 70 students from more than 20 school districts had to be relocated.

Weaver wanted to know more. She went to the CEO’s office, where she was shown a video of a staffer trying to control a classroom of students.

At one point, Logan stood up from his desk.

“This aide picks up this stick or spoon — I don’t know what it is, and they won’t tell me what it was — and she goes at Logan with it, and she’s waving it at him like she’s about to hit him with it,” she said. “And he gets this look of fear over his face. And he puts his hand up, trying to block her from hitting him with this thing. And he hurries up back to his seat, and you can see how scared he is.”

Weaver said the aide started screaming and cursing at another student. Then, Logan stood up again.

“She comes up behind Logan and she shoves him on his back into his desk,” she said. “And so that happened on October 24.”

Weaver didn’t know about it until January.

Steve Verano is Avondale’s CEO.

“Actually, we learned about that earlier and the staff member was terminated at that time,” he said. “I didn’t find out about it until later when I was watching the videos, and at that time I met with the district and the parent and certainly apologized. I was very disappointed to see that. That is not indicative of the care that we provide here at Avondale House at all.”

That use of force was part of the reason the school was not reapproved by TEA, along with issues related to restraints.

Verano said restraints are supposed to be a last resort.

“We’ve looked at the nonapproval, noncompliance issues and addressed them with our team,” he said. “We’ve done some retraining on appropriate use of restraints and our policies and procedures. We did retraining on de-escalation techniques, which is an important part of our training.”

Child Protective Services said it completed two investigations there over the past year. Avondale said the staff members from each incident were terminated.

A recent court injunction allowed eight students to remain. But districts can’t send new students until Avondale regains approval next year, placing a strain on other off-campus programs that already didn’t have enough available spots to meet the high demand from families.

“We still have some students here, and several of the districts unfortunately weren’t able to find suitable placements for all their kids, and so they’re kind of in limbo right now — which is why we’re excited that the judge ruled in our favor that we can continue to serve them,” Verano said. “For me, the real story of this is the lack of resources in the community for students with disabilities of this type because there just aren’t that many places that they can go.”

In a written statement about the injunction, a TEA spokesperson wrote “TEA is committed to ensuring that students with special needs receive the services they are entitled to in an environment that is both welcoming and safe.”

“The Agency believes it showed significant evidence that such standards of service were not being met by Avondale House and continues to stand behind the findings of its investigation,” the statement continued. “As a result of the court’s decision, TEA will pursue appropriate legal recourse to protect these students.”

Logan is now at another program, but Amanda Weaver isn’t okay.

“Logan is nonverbal,” she said. “He can’t come home and tell me that someone’s hurting him at school. He can’t tell me that.

“And for me, it’s this overwhelming guilt that now, twice, I placed him somewhere where I thought that he was safe, and he wasn’t. And there’s just no accountability.”

Advocates want to change that this legislative session.

Jolene Sanders-Foster is advocacy director with the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities.

“In addition to ending the use of violent restraints and unnecessary use of force, we need to address accountability,” she said at a press conference in January.

House Bill 459 — also known as the “No Kids in Cuffs” bill — would ban restraints for students 10 and younger outside of extreme situations.

It was authored by state representative Lacey Hull.

“There are de-escalation and intervention strategies that are designed for these situations,” she said. “By explicitly stating in law that ‘No, you cannot restrain a student,’ we hope to protect children from these traumatic incidents.”

House Bill 133 would prohibit “using any variation of a floor or ground restraint or other technique that results in immobilization of the student in a prone or supine position.” TEA reported one such incident at Avondale House, and the Fort Worth Star Telegram reported that a student died in 2021 after school staffers used that type of technique.

Advocates also want lawmakers to make it easier for educators to be held liable for abuse, and schools to add abusive staffers to the Do Not Hire Registry.

Last session, the “No Kids In Cuffs” bill passed in the house but died in the senate. Advocates hope the bill and other changes will pass both chambers and be signed by the governor this time.