From Texas Public Radio:

State officials decided they no longer wanted to be legal guardians of 42 minors who ran away last year, a practice it repeated the past five years, adding up to around 170 youth under 18.

Every year, around 2,000 of the more than 45,000 kids in Texas’ foster care system go missing – often running away. Last year, that number was 1,767 children.

The overwhelming majority of kids are located, according to a report from DFPS, about 85% were in 2021.

Five percent — or 87 kids — weren’t found and the state asked a judge to end its responsibilities for them.

Why would the state decide a missing or runaway kid should be cut loose from the state’s care and oversight?

“The decision of whether to maintain DFPS responsibility over a youth or terminate that responsibility is up to the individual courts. I can’t guess what each judge’s reasoning would be for terminating those cases,” said a DFPS spokesperson.

While technically true, according to lawyers and judges TPR has interviewed, these actions don’t occur without DFPS lawyers asking for them.

“In my experience, I haven’t had that request made by someone other than the state,” said Aurora Martinez Jones, a judge for the 126th state district court in Travis County that specializes in child protective and foster care cases.

The state doesn’t appear to have a written policy for when a missing minor child will be released from conservatorship. The only time the legal action is referenced in the statewide guide for locating Department of Family and Protective Services kids is when a child turns 18 on missing status. Child Protective Services workers and special investigators must continue trying to locate the child unless a court ends its responsibilities.

Half of the foster kids who the state terminated conservatorship of turned 18, and the state effectively said they were adults.

The other half, or about 42 minors, were under the age of 18 when the state petitioned a judge to end its care.

A federal report last October shows that nationally, 528 kids exited foster care while considered runaways — which includes those that age out and minor-children. Texas reported 93 kids that year — meaning Texas could represent more than 17% of all the kids who left foster care while considered missing or runaway.

How Texas compares by state is largely a mystery as many states don’t make the data public, or categorize things in the same way. States like Nebraska and many others don’t publish the data and request hundreds of dollars in fees to find out.

In Georgia the practice was so unpopular it garnered significant media attention and the state ended a policy in 2016 of terminating guardianship if a child was gone for six months on runaway status. But it turned out the state was still doing it in 2018, as news organizations found another 50 incidents.

Texas DFPS said the decisions are in individual children’s files – which are not open to the public – and that the responsibility ultimately lies with judges and courts that make the rulings. There could be any number of reasons for the decision — we just don’t know.

Martinez Jones said one of the most important times a child needs a parent or guardian is when they run away or are missing.

“Absolutely, because if they do end up in a situation where they need to reach out for help, who is it that they’re going to actually reach out to?” she asked.

Runaway youth are more often than others the target of sex trafficking and abuse. Last year, 119 kids in Texas were victimized while missing. In Martinez Jones’ experience, when kids do get back in touch with the court while missing —which is common— they are rarely in a better situation.

According to the state, two foster children died while missing last year.

For this and other reasons, she said while she has been petitioned by the state numerous times to terminate a minor child’s conservatorship, she has only ever followed through once — when a child reunited with a family member who continued to avoid interacting with CPS.

A missing child means a lot of calls and coordination for the system.

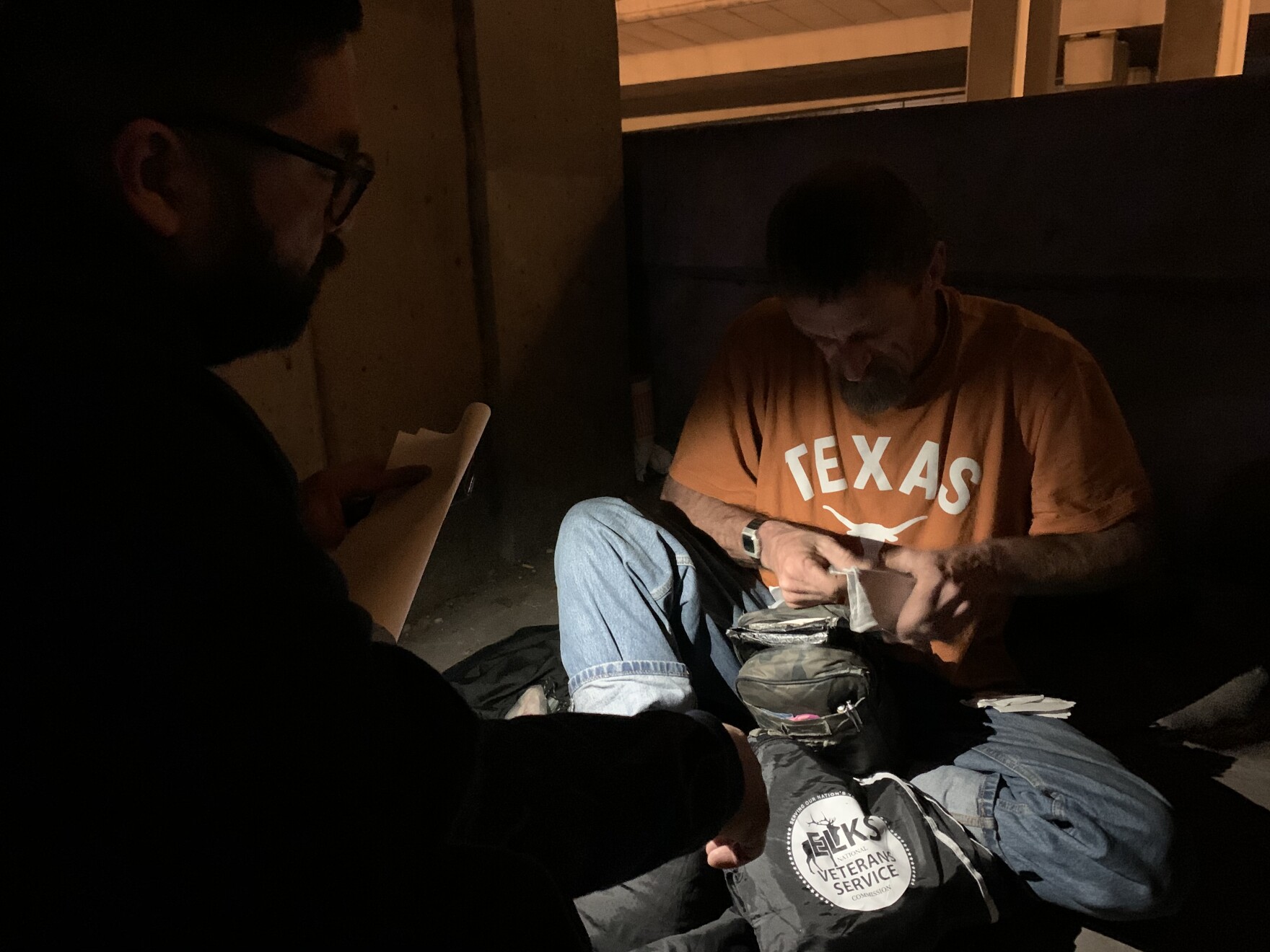

When a kid goes missing, their case manager contacts local law enforcement, their supervisor, the statewide intake system, the court, the children’s parents (if they still have rights) and updates a federal database along with a host of other tasks. Statewide intake notifies CPS field staff. The child is then assigned to a special investigator who is tasked with locating them. Multiple staff are then tasked with meeting monthly or quarterly on the status of the child, oftentimes updating a judge.

All this has to continue until the child is found or until a court ends the state’s conservatorship.

Is the state simply trying to reduce its caseloads and legal liability?

Two former DFPS workers said ending legal liability likely motivated the state’s actions. Neither of the former employees worked in conservatorship nor ever participated in a court action to remove the state as a custodian.

“I think it to some extent, it is a matter of resources, both financially and emotionally,” said Christine Hortick, President of the Bexar County Children’s Court Ad-Litem Attorney Association — a group of 90 lawyers in the county that represent parents and children in abuse and neglect cases.

A federal report pointed out obstacles to locating youth include uncooperative friends and families of the youth, relying on law enforcement to find youth and kids who habitually run away.

“One state agency said the caseworkers’ biggest frustrations are typically related to children who go missing frequently, or who return to care, and that are missing very shortly thereafter,” said Brian Whitley with the U.S. office of the inspector General for the Health and Human Services committee, reading from a May report.

Hortick sees the practice as extremely rare. In 14 years of practicing as an ad-litem, she estimates she’s only been involved in the process three times. She is currently working on a case that may end up with the state terminating its conservatorship.

Her client is a 17-year-old girl who ran away from a placement and is believed to be hiding somewhere in San Angelo. She has been in contact with the Special Investigator as well as her case worker confirming that she is OK but that she won’t be returning to DFPS custody.

“It’s one of those things where everybody in the (court)room is frustrated, because what can you do? I don’t think it’s in any way a situation where people don’t care and they just kind of wash their hands of them,” Hortick said.

There is no federal policy around the practice of terminating youth conservatorship when kids are on runaway status.

The issue raises a tough question for many: If a state has limited resources a child refuses to accept help or return to the state’s custody, Hortick asked, isn’t it appropriate to let investigators focus on youth that will?

Add to this situation what experts have called Texas’ “placement crisis,” where the state was short as many as 1,000 foster beds for youth last year. Those beds were largely for kids who are the most difficult emotional cases. They are more likely to run away. The result has been a blossoming of what’s called “child without placement” scenarios (CWOP), where kids are being put up in hotels or in residential homes rented and staffed by CPS.

Problems plague CWOP placements with untrained staff who aren’t meeting the mental and physical needs of the youth staying there. A court report from earlier this year said the unlicensed facilities often saw more runaways.

When youth have their state custodianship terminated, it often includes what’s called “Trial Independence.” That allows the youth to reenter DFPS custody if they come back later. At times when the state terminates its custody of a youth, a parent or guardian who still has some reduced legal standing is reinstated as custodian.

Most of the 110,466 kids who went missing from foster care across the country last year were 15-17 years old — about 65% according to a federal study. In Texas, they run away an average of three times. DFPS said the most common reasons given were disliking the placement rules, anger at CPS or the system or the desire to be on their own.

For many, the solution is creating a system that kids don’t want to run from. Texas ranks second behind California in the number of runaway episodes each year.

“We have a foster care system where kids continue to experience abuse and neglect, they experience instability. And so for a lot of kids in foster care, running away feels like the right option to them,” said Kate Murphy with Texans Care for Children.

For her, it’s keeping kids out of foster care to begin with. Murphy said the state should increase funding to mental health and substance abuse resources that can be used for early interventions

“We know that a lot of the children who are winding up without placement came into care, not because of abuse or neglect,” she said, “but because they had an unmet mental health need.”

But that doesn’t address the kids who are currently running away from the system.

“It doesn’t necessarily get the attention that it needs,” said Whitley. “It’s not necessarily the headline news story on the day-to-day, but it is a very important issue for the children in foster care that are experiencing being out of placement or being on the street or being in an area that’s not the safest spot for them. And the more attention we can get on this issue, I think the better and safer the children will be.”